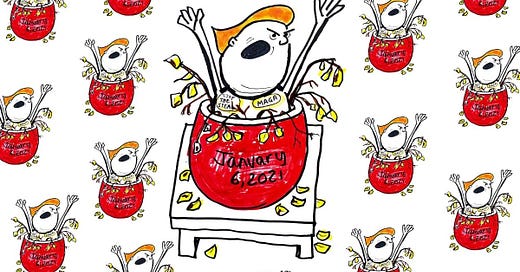

Donald Trump’s legacy — a proto-fascist movement we might call Trumpism — includes a Supreme Court rapidly taking America backwards, state legislatures suppressing votes and taking over election machinery, and an emboldened oligarchy taking over the economy. While the January 6 committee is doing a fine job exposing Trump’s attempted coup that culminated in the attack on the Capitol, it is not part of the committee’s charge to reveal why so many Americans were willing — and continue to be willing — to go along with Trump. Yet if America fails to address the causes of Trumpism, the attempted coup he began will continue, and at some point it will succeed. My purpose in today’s post (and others to come) is to begin to expose the roots of Trumpism , and suggest what must be done.

Let me start with some personal history.

In the fall of 2015, I visited Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Missouri, and North Carolina. I was doing research on the changing nature of work in America. During my visits I spoke with many of the same people I had met twenty years before when I was secretary of labor, as well as with some of their grown children. I asked them about their jobs, their views about America, and their thoughts on a variety of issues. What I was really seeking was their sense of the system as a whole and how they were faring in it.

What I heard surprised me. Twenty years before, many had expressed frustration that they weren’t doing better. Now they were angry – at their employers, the government, and Wall Street; angry that they hadn’t been able to save for their retirement; angry that their children weren’t doing any better than they did at their children’s age. They were angry at those at the top who they felt had rigged the system against them, and for their own benefit. Several had lost jobs, savings, or homes in the Great Recession following the financial crisis. By the time I spoke with them, most were back in jobs, but the jobs paid no more than they had two decades before in terms of purchasing power.

I heard the term “rigged system” so often that I began asking people what they meant by it. They spoke about the bailout of Wall Street, political payoffs, insider deals, CEO pay, and “crony capitalism.” These complaints came from people who identified themselves as Republicans, Democrats, and Independents. A few had joined the Tea Party. Some others had briefly been involved in the Occupy movement. Yet most of them didn’t consider themselves political. They were white, Black, and Latino, from union households and non-union. The only characteristic they had in common apart from the states and regions where I found them was their positions on the income ladder. All were middle class and below. All were struggling. They no longer felt they had a fair chance to make it.

With the 2016 political primaries looming, I asked them which candidates they found most attractive. At that time, the leaders of both parties favored Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush to be the Democratic and Republican candidates, respectively. Yet no one I spoke with mentioned either Clinton or Bush. They talked about Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. When I asked why, they said Sanders or Trump would “shake things up,” or “make the system work again,” or “stop the corruption,” or “end the rigging.”

The following year, Sanders — a 74-year-old Jew from Vermont who described himself as a democratic socialist and who wasn’t even a Democrat until the 2016 presidential primary — came within a whisker of beating Hillary Clinton in the Iowa caucus, routed her in the New Hampshire primary, garnered over 47 percent of the caucus-goers in Nevada, and ended up with 46 percent of the pledged delegates from Democratic primaries and caucuses. Had the Democratic National Committee not tipped the scales against him, I’m convinced Sanders would have been the Democratic Party’s nominee.

Trump — a sixty-nine-year-old egomaniacal billionaire reality TV star who had never held elective office or had anything to do with the Republican Party, and who lied compulsively about almost everything — won the Republican primaries and then went on to beat Clinton, one of the most experienced and well-connected politicians in modern America (granted, he didn’t win the popular vote, and had some help from the Kremlin).

Something very big had happened, and it wasn’t due to Sanders’s magnetism or Trump’s likability. It was a rebellion against the establishment. That rebellion — or, if you will, revolution — continues to this day.

Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush had all the advantages — deep bases of funders, well-established networks of political insiders, experienced political advisors, all the name recognition you could want — but neither of them could credibly convince voters they weren’t part of the system, and therefore part of the problem.

When I interviewed these people, the overall economy was doing well in terms of the standard economic indicators of employment and growth. But the standard economic indicators don’t reflect the economic insecurity most Americans felt then — and continue to feel. Nor do they reflect the seeming arbitrariness and unfairness most people experience. The indicators don’t show the linkages many Americans still see — between wealth and power, crony capitalism, stagnant real wages, soaring CEO pay, their own loss of status, and a billionaire class that has turned our democracy into an oligarchy.

The standard measures also don’t show that for four decades, Americans without a four-year college degree have worked harder than ever, but gone nowhere. If they’re white and non-college, they’ve been on a downward economic escalator.

Finally, the standard measures don’t show what most Americans have caught on to — how wealth has translated into political power to rig the system with bank bailouts, corporate subsidies, special tax loopholes, shrunken unions, and increasing monopoly power, all of which have pushed down wages and pulled up profits.

Much of the political establishment still denies what has occurred. They prefer to attribute Trump’s rise solely to racism. Racism did play a part. But to understand why racism (and its first cousin, xenophobia) had such a strong impact in 2016, especially on the voting of whites without college degrees, it’s important to see what drove the racism. After all, racism in America dates back long before the founding of the Republic, and even modern American politicians have had few compunctions about using racism to boost their standing. Richard Nixon’s “law and order” campaign on behalf of “the silent majority” was an appeal to racism, as was Ronald Reagan’s condemnation of “welfare queens,” and George H. W. Bush’s use of Willie Horton against Michael Dukakis. Racism was also behind Bill Clinton’s promises to “end welfare as we know it” and “crack down on crime.”

What has given Trump’s racism — as well as his hateful xenophobia, misogyny, and jingoism — particular virulence has been his capacity to channel the intensifying anger of the white working class into it. It is hardly the first time in history that a demagogue has used scapegoats to deflect public attention from the real causes of their distress, and it won’t be the last. In 2016 Trump galvanized millions of blue-collar voters living in communities that never recovered from the tidal wave of factory closings. He understood what resonated with these voters: He promised to bring back jobs, revive manufacturing, and get tough on trade and immigration. “We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country, and that’s what they’re doing,” he said at one rally. “In five, ten years from now, you’re going to have a workers’ party. A party of people that haven’t had a real wage increase in eighteen years, that are angry.” Speaking at a factory in Pennsylvania in June 2016 he decried politicians and financiers who had betrayed Americans by “taking away from the people their means of making a living and supporting their families.”

Worries about free trade used to be confined to the political left. But by 2016, according to the Pew Research Center, people who said free-trade deals were bad for America were more likely to be Republican. The problem wasn’t trade itself. It was a political-economic system that had failed to cushion working people against trade’s downsides or to share trade’s upsides – in other words, a system that was rigged against them. Big money was at the root of the rigging. This was the premise of Sanders’s 2016 campaign. It was also central to Trump’s appeal (“I’m so rich I can’t be bought off”) — although once elected he delivered everything big money wanted. It is well worth recalling that in the 2016 primaries, Bernie Sanders did far better than Clinton with blue-collar voters. He did this by attacking trade agreements, Wall Street greed, income inequality, and big money in politics.

More to come on this, but it’s getting late and I’m dead tired.

I largely agree with everything Dr Reich says here; except for the omission of the influence of Dark Money (led, mostly from what I can infer) by Charles Koch. Though the Koch brothers did not support Trump when he appeared, they still created the Tea Party, and so many other of the anarchistic, even white supremacist groups out there across the radical right landscape. Trump is hardly intelligent enough to manage anything like that, and is a simply a loose cannon, rolling around on the deck of the unwieldy battleship of a political party that Republicans have become…IMHO. Due to its very shadowy nature, the mainstream media never touches Dark Money, but I think it is the real elephant in the room that NEEDS to be discussed, if we are to be realistic about what has happened to US politics — and how to counteract it.

Yes, the Koch's and cronies formation and success of ALEC unopposed and ignored by the leadership of the Democratic Party did more to prepare a justifiably disgruntled population for "trumpism" than the "trumpster" himself

Also illegal foreign influences. Mueller report. Russians supported Trump. Ran psy-ops campaigns, made illegal contributions. Check out the relationship of Derepaska and McConnell.

Don't want to sound like a xenophobe but Saudis have been undermining our economy and support Republicans. Virtual control of our oil industry, major donors. Funded Murdoch's Fox disinformation network beginning in 1973.

Also, Chinese influences. Check out the relationship between Elaine Chao's family as contractors with the Department of Transportation. When I worked for DOL, the Chinese military hacked into my security clearance. I was one of millions. Justice Department did nothing https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/chinese-hackers-breach-federal-governments-personnel-office/2015/06/04/889c0e52-0af7-11e5-95fd-d580f1c5d44e_story.html

@Daniel. You are a well informed individual! Thank you for putting some facts on the table!

Ah. Thanks for leading off, Dan. I'd worried I might sound paranoid if I mentioned overseas influences. Thanks to 20-40 years of neocon adventurism, quite a few people around the world hate and resent the United States. Because we blew up their homes, killed their families, wrecked their countries - not so much like GWB said "because they hate our freedoms."

The United States has an opportunity to reverse that trend simply by NOT blowing up peoples homes, etc. That may earn us a little grudging forgiveness if we are contrite.

But there are also people who HATE the United States and have always done so, and who have no chance of being dissuaded. In general, if we can leave them the hell alone and stay out of their playground, we won't get into any scuffles. So lets.

There are several organizations that institutionally fall into the irredeemable hatred class. Many of the secret security agencies in certain places do so, and nothing will assuage them unless the US is nuked into a glowing hole. We should ESPECIALLY leave those people alone - the security services in Iran, military security services in China, and "the big one" that has conspired against the US for nearly 100 years. The KGB, in its various forms and manifestations.

The MOIS (Iran) and KGB and others are set on a goal to oppose and destroy the United States. We are pretty safe as long as we don't f* with their countries and do a little bit of home security tidying.

But think with me. What happy moment they might have if they instill in the United States a ruthless and misguided movement that claims to "Make America Great Again," but by all actions, aims and inclinations, slashes America's throat in opposing the very elements that make us proud of our country?

I suspect that, since the KGB spent decades trying to strangle out the US - at first due to ideological opposition to capitalism, and then as when communist ideology died in the USSR to be replaced by big-shot-ism the KGB just continued trying to strangle America. We silly Westerners pretend that when the USSR evaporated, the KGB and Red Army went pfft! and they all went off and became average citizens. HAH! The KGB and Red Army barely felt the "Fall of the USSR." The nameplates changed on their desks, the flag looked different. The same mindset remained.

You can't do better against a country than recruiting its own citizens, using MICE (Money, Influence, Compromise and Ego.) Quick - if you wanted to recruit an American, who would be your ABSOLUTELY FIRST PICK? Someone who endlessly covets money and no amount is ever enough - who is transparently vain and strives to be a Man of Influence in every circle he wanders into - someone who could be easily tricked and trapped by some Ivana agent and manipulated to marry her, and continued to have questionable connections all his life - and ego, what more is to be said. Can we dare wonder if the MAGA movement is threatening to destroy America, because from the get-go that was its reason for existence? Now call me paranoid.

I don't think you are paranoid. I think you are right. I also think it was why Mitch McConnell ushered Trump to power. I believe McConnell is deeply involved with the Russian organized crime. Look up McConnell and Oleg Deripaska scandal. McConnell is the reason we are living in this dystopian America that we're living in now. He calls himself the "Grim Reaper" because the senate is where bills go to die. This country is one where Americans die too, from guns, underfunded and bad healthcare, now coming, back alley abortions, and on and on.

There was a well-established problem with recruiting Americans to act as agent for foreign powers. The KGB did a smash-up job recruiting based on ideology with the Cambridge Five. But Americans didn't seem to be easy to recruit unless they were already out-and-about Communists. The postwar Left, especially the union folks, made for slim pickings for ideological recruitment.

It's a particularly poignant issue that in the 60's, the blue-collar left didn't like the hippy-dippy-college radicals, many of whom were all sorts of different leftists - Trotskyists, Neocoms, Luxemburgists, Spartacusers - etc; the lunch-bucket crowd thought they were all paid off by the Soviets. After the dust had settled...they weren't. They were just a bunch of loudmouth thinking Americans proposing change like quitting SE Asia. Two sides of fairly loyal Americans throwing rocks at each other. Figures. But not prime KGB material.

It was only until the USSR changed its recruitment strategies from picking off the ideologues to picking off the greed-heads, that they hit the jackpot. In an unsourced and dubious quote, “Lenin wrote, ‘When it comes time to hang the capitalists, they will vie with each other for the rope contract.'”

But when it came to finding some screw-thy-country boys, you just can't top a Republican. That's why they get all puffy about patriotism. Cover story, comrades.

Oh yes, that patriotism total bull____! Trump draping himself in the flag! Very interesting Steve. The GOP has been conspiring with Russians, intelligence and crime for decades. McConnell is amazingly well hidden to the American public. This is all so very frightening because this IS HAPPENING and people are utterly clueless to what is destroying their lives.

I agree with your concept but disagree with your terminology. Except for a very few hippy communes in the late 60's and 70's and they don't really count, there is not and never has been communist country on this planet, regardless of what they call themselves. Russia, China, North Korea, Cuba, are and have been authoritarian regimes. Like all authoritarian regimes they are the exact opposite of communism (and socialism for that matter) Like the trumpster they don't give a rat's ass about working folks. They have all had a small, autocratic, very wealthy group spouting out pure crap about equality while sitting in their dachas drinking vodka and smoking cigars. Nazi Germany called themselves the democratic socialist party. LOL, they were fascists, just another form of authoritarianism. If we aren't very careful that's where the current republicans hope to take us.

The battle is Plato vs. Lord Acton. The Republic postulated persuasive but informed rule by the Wise, and all decisions have the recourse to Wisdom. Acton countered with "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men…" Great lust outweighs great wisdom when the gloves come off. That's the struggle of human nature that influences the governments of a collective nature, and why they usually pitch over quickly.

Thank you Steve. Yes, I am familiar with that quote and recognize the difficulty of the conflict between personal interest and public interest. I just prefer to hope that public interest will rise over authoritarian personal interest.

@Fay. Thanks for your very firm grip on the real history of Marxism. Cuba almost had more socialism than the rest of those you mentioned, but still had to be authoritarian. Did you ever think that the so-called communists face the same challenges that Democrats face? The moneyed interests can't stand the common people to get too much of the treasure, so they go to work to capture WHATEVER regime is in power. Money, money, money... Ergo no communism, and only a pale shadow of socialism in European countries with well-established democratic values. We should talk about how the moneyed interests raped the UK with all their demagoguery about "English pride" and "independence" from the (characterized by oligarchs) dominating EU. I'm so desperate about the UK that I want Tony Blair back!

Thank you, Benjamin. I will agree but we need to include GREED, for money, and for power.

Steve O’Cally - All you have to do to think that AT LEAST ONE other nation has their mitts on our American throats is to read "The Mueller Report." I bought a hard, redacted copy shorty after it released.

Had it been as public as the current bombshell January 6th Insurrection hearings are now, I fully believe IT would have sunk _rump just as bad.

If the Chinese ever get their foot on our necks we will suffer. They remember the 19th century when the West invaded and dominated them.

Their history shows that they are patient and seemingly never forget who has messed with them throughout their history.

They will never forget what the Japanese did to them. I spent nearly 4 years teaching at universities in China, always within easy access of Nanjing.

I am an historian with a strong interest in historical museums, but I never did make it to the museum in Nanjing that focuses on "The Rape of Nanjing". This was primarily because absolutely none of my colleagues at either of the universities that I taught at in China had any interest in visiting what is generally referred to in guide books as the bloodiest museum in the world, and I did not really want to go alone. I assumed I would eventually find someone who wanted to go with me, but I never did.

Then stop supporting far left ccp supporting morons like biden.

Ur suffering from Orange Turd Reich Christofascist Trump Derangement Syndrome.

@Beadgurl. A Russian troll masquerading as a woman. How ridiculous! But Biden's problem is that he is not left enough! Too much of a traditionalist. We needed him, perhaps, to establish a sense of normalcy after the traitor was finally run out of office, but the progressives, liberals, centrists and true democrats need to look for a new "look" in 2024.

Well, I've never been to Russia and it sounds like you don't believe a woman can make a direct, concise comment since you're implying I'm a man. Thanks. Biden is a demented fool who has accomplished nothing in his 40+ years of milking the political establishment. Hence the desperate need for term limits. I'm not sure what you think your heroes on the far left will accomplish because Uncle Joe has done a fine job of throwing America into chaos and making the US an even bigger laughing stock in international politics. But even the donkey party realizes he's the only trick in town thanks the new record-setting embarrassment that is Willie's Side Piece. I'll never forget her explanation of the invasion of Ukraine. Just magical. The problem with far left progressives is rational people capable of independent thought cannot take them seriously. Aoc is a fine example of a complete moron with too much power and not enough intelligence to use it effectively. Surely you realize that left-wing agendas like socialism, communism, and naziism will only make you slaves to a state. History proved that. Why do you think refugees from Venezuela, Cuba and China emigrating to the US are voting conservative? They've lived under leftist totalitarian regimes. I'll take my lessons from history and from folks who've lived it first hand. No far left totalitarian government for me thank you! Enjoy your day and thanks for the dialog!

Then move out of U.S. if that is where you actually live!

This is the new desperate plea of those failing to make their argument. You could have more easily pointed to one or more of the poster's errors and misconceptions, which were many.

So are you acknowledging that the left in the US is moving towards totalitarianism by advocating that I move? I love my country, the United States of America, and I will stick with it thanks!

@BeadGurl. You lost a chance at credibility when you put "naziism" (the purview of the right, white nationalists and autocrats) in the same list with your other bugaboos that you ascribe to the left. Just another obvious attempt at "what aboutism" and false equivalency. I think I can stop with you now since everyone reading already knows where you are coming from.

Actually, its a fallacy that naziism is a right-wing movement. Any and all left wing movements center on control by and for the State. Naziism is just the competing sister of communism. And they are the extreme forms of socialism. All on the left, I'm afraid. Have a great day!

bye-bye, trollgirl.

And, to a slightly lesser extent, the 17th and 18th centuries.

Daniel Solomon - I do not think it is "racist" to pin many of America's current problems on the corrupt, hateful regime in Saudi Arabia. WHY do you think obsolete fossil fuels are STILL considered " viable" by most?

@Daniel H. Actually fossil fuels are built into the physical infrastructure of the modern economy. It will take many years to refresh billions and billions of dollars of facilities, equipment, distribution networks. Painful, but we must do it to save the world from destruction.

I sure hope you plan on donating your vast wealth to tear down buildings and rebuild like AOC thinks will happen and find a fuel source as efficient.

Because they are not obsolete and are certainly more viable and cheaper than your green solutions...which, BTW, rely on electricity to support them...wind farms, electric cars, all rely on some support from the grid. And no one talks about viable disposal programs for all those windmill blades that will never decompose, the tesla batteries that are beyond toxic. Even solar has its limitations. I've seen large solar farms...not attractive and take up arable land. Im all about conservation, reducing the pollution caused from massive trash dumping but I never hear a competent, well thought out solution from the left on how we mitigate the trash and pollution from so-called "green" solutions. And btw, i have a solar array, practice water conservation by relying on a rainwater collection system and recycle like mad.

@BeadGurl. Masquerading as a woman - shame on you. But you are quick to put up shaky critiques of the liberal/progressive response to climate change, but offer NOTHING credible that you can say the right is doing to change the trend line away from increasing damage to the planet. No, you Saudi-defending, oligarch-defending, Putin-defending trolls are just trying to undermine the effective and on-going educational efforts of those who are truly concerned about and working to mitigate climate change. The fact that it is a difficult problem is not equivalent to those actively opposing all efforts.

I do everything you're doing as well (solar, heat pump, collecting rainwater, next step is a graywater system). And I still think nuclear is going to be our default option, despite it's very obvious defects (waste disposal.) I used to be staunchly anti-nuclear, but have changed my mind in the last 15 years. It's going to be an interim solution until fusion's perfected (likely in 50 years.) But to keep on using carbon based fuels when it is OBVIOUSLY going to kill us, and rejecting nuclear due to problems down the road, is analogous to saying "I've got cancer (carbon fuels) but am unwilling to lose my hair to chemotherapy (nuclear)."

Daniel, YES, thank you for this.

Agree on the ccp aspect. McConnell is no friend to the people of this country. The rest, well, your dem buddies are in just as culpable, if not more so, in bringing down this country. And if you're still buying into the Russian hoax thing, enough evidence has been made public to completely demolish that fairy tale.

That is BS. No hoax. There is no Democratic equivalent.

The obstruction of justice counts in Mueller remain viable. Mueller and Barr were both Republicans. Mueller found that the Russians aided Trump. Said he could not find that Trump colluded. A jury, not the prosecutor is supposed to make that determination. Manafort and 32 Russians were prosecuted and have been adjudicated as guilty.

Newer evidence implies that Trump indeed colluded with Putin on many levels. The phony evidence proffered by Giuliani in the first impeachment came from Russia. The episode with the Taliban reinforces my argument. He didn't need to negotiate with the Taliban to get out of Afghanistan. At that time, they were allied with Russia. He tried to undermine NATO, destabilize the Ukraine, etc.

The proof of Hillary's involvement in that is not something to ignore....

Turned out to be BS.

Don't think so.

@BeadGurl. You trolls and bots are masquerading as women now! LOL. This false equivalency and defense of Putin are both a dead give away. Even the worst of Faux watchers don't think the Russia thing is a hoax - not anymore anyway - because the evidence is exactly the opposite of what you wrote. See Mr. Solomon's pointed reply.

Yeah, I saw it.

Aw, c’mon. Putin calls him “AGENT ORANGE.” (Except Agent Orange actually went to Vietnam.))”

Good one!

@Steve. ;-D

SUPRISE HEARING: (Not a reply, Ms Reid.)

Where to "attend" the >surprise< 1/6 hearing: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/watch-live-jan-6-committee-hearings-day-6

Thank you. I watched it on CNN. Very revealing.

End Citizens United!

That and the dissolution of the obsolete-since-the-1860s electoral college may be all we need to END the also obsolete _rumplican party.

This corrupt ruling by the Conservative Fascist RepugliKKKan SCOTUS began our slide into Oligarchal Fascism.

I agree that the ruling showed an appalling lack of logic and a surprising leap of cynicism on the part of the courts. The question we must ask ourselves is how in the world we got there.

Trump met with the Tea Party in 2013 to discuss running for president. The Kochs may be under the radar but their fingerprints are all over our loss of democracy.

The Koch's and all their minions in the tea party and ALEC despise democracy or any form of government other than pure authoritarianism. Authoritarianism is the only form of government that can fulfill their thirst for power and wealth. As I said before what they really want is to return to medieval feudalism, but with all the modern conveniences.

Rick. I agree with you. There is dark money on BOTH sides. Koch and Soros plus throw in Zuckerbucks, Gates and Bezos. Wait until we start hearing from Elon Musk in the future. Sadly money talks and bullshit walks.

Comparing Soros to the Kochs and other right-wingers is a false equivalence. Generally, his money has helped Democrats survive in spite of the DNC. If you heard otherwise, it might have been from Fox.

Cecelia repeatedly repeats Fox disinformation.

No, actually it isn't. If you still think the dems are pro-america, you are wrong. There are globalists on either side of center who want to see the US crumble. If you can't look at the left and right objectively you'll miss what is actually happening. It would be more productive if everyone looked at facts and left ideology behind. I love how you guys vilify Fox but you think cnn and pmsnbc are legitimate news sources. I cant take any alphabet talk show as a news source anymore. Its laughable.

Fox is controlled by a family that was funded originally by Saudi money. Ownership has left the US. Even their reporters admit they don't report the news due to management policy.

At present they have exposure to billions in defamation lawsuits. More to come.

I'm well aware of who runs fox. Al waleed bin talal had a 7-8% stake. When he bought in, terrorism coverage went down the toilet. A fox producer was busted on camera saying they are center left and push the neo con agenda for ratings. I trust them no more or less than I do the far left Democrat propaganda machines of cnn and pmsnbc. If I want a really good belly laugh, I pass through joy reid or one of the other unhinged commentators there. Don lemon meltdowns are always fun to watch.

If you think they are the "left" you're nuts.

There is no comparison on CNN or MSNBC to apologists for the Proud Boys, Boogloo Boys, Oathkeepers and other allies of yours who would EXTERMINATE me if they could. Tucker live from Budapest. Propaganda from white supremacists.

What does “Give gift” mean, next to your Reply button?

No clue. Ask Substack. I see that with a lot of posters. Not sure why that would be there tbh.

U must be a Russian or Chinese disinformation agent. U and Orange Turd Reich Christofascist TRAITOR Seditionist Insurrectionist Felon Conman Grifter LOSER Corrupt Neo-Nazi Megalomaniacal Sexist Misogynist Narcissist Nihilistic Sociopathic Psychophantic TRUMP.

Yes, yes, the take over of Republican party by Teaparty, “Let’s make some noise.” Noise without substance, level of invested interest of a gnat. Cheap and shiny, butterflies trajectory, to circle looking for sweet stuff without a mission but plenty-resources for gull’s brawl over anything, contrarian interests (partly sense of no stake plus enthusiasm for entertainment at expense of anybody). Tabloid-party members, made-up stuff to unseat perceived know-it-alls, box-office hit style outrage (formulaic conflict and outrage), just good fun while fictional world of simplistic solutions has “educated” large cohort of people to trust no one, gunslinger mentality represented in video games and celebrity power. “That’s outrageous” messaging, tale (garbage writers) wagging the dog.

Agree. Campaign reform is issue #1.

Molly Ivan's book "Bushwhacked" was an eye-opener. Corporations rewarding politicians for removing environmental restrictions during the Bush 2 administration. Now, the "think tanks" under the cover of education funnel untraceable amounts of dollars to campaigns. The Heritage Foundation. Dark money, indeed.

@Rick. Thank you!

Koch didn’t start the Tea Party and it was the Tea “Parties”, a group of loosely affiliated break away thinkers including Ralph Nader. If it was co-opted by the Republicans it was also destroyed by the same.

Dark Money is the Coalition for National Policy. People who have the money, the influence the plan to form America into their way of thinking.

Correct, but tRUMP is like an umbrella Dark Money can take advantage of. Sorta like ‘hiding in plain sight’. When his campaign took off I likened him to a pimple coming to a big nasty head. It was/is a symptom of a a huge deep infection coming to a head!

Funny, it just hit me while reading this thread that the term "Dark Money" has a strong resemblance to the physicists' "Dark Energy." A mysterious force that mucks up everyone's calculations ...

If I may be a bit trite, money corrupts. As long as it takes big bucks to run for office the sources of the money will want to be protected. Dah!

Money Corrupts Power. Absolute Power Corrupts Absolutely.

Do not forget the useless billionaire's political arm: Moscowmitch. His SOLE reason for existance is to destroy America and ALL rights so said useless billionaires can extract every single penny they can from Americans, _rumplican and American divide be damned.

And you don't think Biden, Soros, Pelosi etc aren't in on that too? Oh dear.

@BeadGurl. Pelosi's House is a productive engine of constructive legislation. Most of it dies in the Senate. Your efforts at creating equivalency won't fly, and I won't let your crap go unanswered (even though everyone on here already knows you are a machine/bot/propagandist).

Dear ts1213, I realize you are probably a trumpster and are trying to defend your choice. So, I would suggest you learn the language. Dark Money by definition is untraceable. It therefore is assumed to come from one of two sources, an American criminal association or a foreign country. It is illegal (and unconstitutional) for any candidate or political organization to accept even one cent from a foreign government. Accepting money from a criminal source, while not illegal would put any candidate in jeopardy as soon as it was revealed (trust me, if traced to say the mafia it would be headlined across the media) While you may personally disapprove of Mr. Soros, the fact that you know he is the donor, precludes the money being "Dark". Unfortunately the Supreme Court decision on Citizens United, which most of us leaning left abhor, has allowed obscenely wealthy persons and corporations from donating as much money as they want to buy favors from politicians and political parties. While the Republican party and its politicians have reaped most of these benefits, it would not surprise me to learn of some Democrats accepting such donations too. As I recall some politician in the 2016 campaign was found to have accepted money from China and sheepishly had to return it.

Hey, leave the name calling for the schoolyard. How can people ever hope to have an intelligent dialog if the fine people of our country regress to scoffing, ridicule and any other form of infantile behavior. We need to get beyond this....please!

@BeadGurl. You are not providing intelligent dialog, just repeating well-worn and well-rebutted tropes.

@ts1213. Soros, and other contributors provide their money via organizations that they are transparently associated with. "Dark Money" is provided anonymously via organizations that are designed to hide the source of the funds. That said, I am not in any way attempting to justify the use of money in politics - that is the very central problem with our so-called democracy.

I will never forgive the DNC for the way they buried Bernie alive. Hillary was so wrong. And now we are paying for it.

Yep. We need Bernie, and I think the powers that be have always been afraid of him. If he’d won, however, they’d have tried to devour him. He’s so good! We can still get behind him.

Bernie will be 80 years old soon. I am 72 and I am not the man I used to be, and in five years I won't be the man I am now. Bernie needs a love child to carry on the fight.

@John. May it be so...

You got it Ben!

AOC.

I see a lot of comments against Russian influence, the hell we'd pay if China took over. How can you support a man who admires Russian communism and wants to turn America into a marxist socialist country? That makes no sense at all.

@BeadGurl. There is no politician in the United States that fits your description! You twist Bernie's real beliefs (democratic socialist, unionist, American).

I like to think of myself as a cool wise person. But the 2016 campaigns and elections taught me that sometimes the wise must use fire to fight fire. As Ukraine wisely went to war instead of appealing to the United Nations, our Democrats should wisely have nominated the passionate, common-touch Bernie to go ruggedly against the coarse, vulgar Trump.

They directed their fire against Bernie by cheating all the way up to Hillary's nomination, remember? (https://clintonfoundationtimeline.com/july-8-2016-hillary-cheated/) In 2020, Obama called each primary candidate so that they would all endorse Biden. Establishment Democrats and the DNC have shown time and again that the progressive wing of the party is their political arch-enemy, not the neo-fascist Republican party.

they ALL dropped out the night before super tuesday ! biden lied about bernie and bernie called him out on it . then biden went back into his bunker, refusing to face bernie in the final debate. i dint vote for biden - i voted against trump . we all watched as bernie was overflowing his venues and biden couldnt fill a VFW hall .

George M. That is what Trump did regarding Obama. Trump was fighting fire with fire. Republicans have never really fought back until Trump. We go too far left. We go too far right. We need to focus on compromise and staying in the center. Why there are so many Independent voters now.

I thought Hillary was the centrist compromiser, and I voted for her in the primary. Enough other Democrats did likewise, and, as some have commented, establishment types tilted the choice for her. We know the results. She got plenty of votes but not enough to overcome the many angry people who refused to vote for her, so they voted in protest against her. I hope the 2016 election will have taught us a lesson. Do not put a gentlewoman in a fight against a bully. An example for 2022: I think the rugged John Fetterman of Pennsylvania may have the anger and bluntness necessary to win blue collar voters back from the Republican and independent folks who liked T.

Both parties lost me, never to get me back. We need a 3rd party where common sense and focus on American sovereignty and economic superiority are the drivers. And term limits for crying out loud. That would eliminate the graft, lobbying and back-door dealing that permeates the swamp.

@BeadGurl. You are a troll. You were never an American, and you were never in an American party. Hell, you are so messed up you are not even a member of the communist party (only because the oligarchic narcissistic Putin does not require that anymore).

Oh dear. There goes the name calling again. Back to the playground with you. If you can't accept an honest comment that has no agenda whatsoever, it speaks volumes about your lack of logic and acceptance. And this is why the far left has a reputation for being illogical and unhinged. Enjoy your day, sir.

BeadGurl. Very well stated. I totally agree with you.

When HRC and her cronies buried Bernie alive they buried their party too. Republicans seized on their good fortune.

@Cecelia. Stupid analysis and not what happened. Your stuff is just an effort to distract from every traitorous act old bone spur did.

YOU my friend is what is wrong with America. It may be a "stupid analysis" to you but my opinion. We are lucky to live in the USA where we are free to share our opinions.

Not when it's disinformation.

after Trump was elected it came to light that Hillary had essentially bought the DNC. It was then explained to the naïve democratic populace that, not being a public entity, there was no requirement to be impartial, fair, honest, etc. So how does one go back to being naïve?

Meanwhile, Republican true believers keep on believing no matter what.

@Earl. Careful sir. You might want to look for a source for your false assertion that "Hillary had essentially bought the DNC." No such thing ever happened.

Benjamin, if you hate bad intel, we are on the same team. Check out Donna Brazile’s “Inside Hillary Clinton’s Secret Takover of the DNC. “

@Earl. Every front runner is the leader of their party.

I think we have gone from “it absolutely didn’t happen” to “ well I am OK with it and you should be too”. Presenting a rather perfect microcosm of what is wrong with this country. Dishonest people suck, no matter who they are.

Absolutely.

I concur with tour statement re the dnc and Saunders. they also left secretary of state alone and out on the line to dry.

i'm always astounded that any rational thinking literate human anywhere in USA would vote for trump for anything at all. as a former NYCer, i was utterly horrified by his criminal shenanigans, his intimidation, hatefulness, racism and misogyny. even before i relocated to NYC from the opposite coast, i was only too well aware of his lack of character, so proximity is no excuse. so believing that trump would do anything other than steal the taxpayers' funds and abuse everyone around him is insane.

GrrlScientist, have u ever seen videos of Jordan Klepper’s interviews of rally goers @ DT rallies?? They are hilarious but also very revealing about the gullibility & genuine ignorance of Blue collar folks & young people! Find them on YouTube & get enlightened about the kind of people DT attracted—angry white Supremacists & fascists who believed their jobs were co-opted by immigrants & People of color rather than admit to themselves they were left behind bec they had no special training or education to help them keep up with technology!! Very sad stupid people but they were committed to his rallies & making a little money selling merchandise!! Jordan is a member of Trevor Noah’s show. Check them out!

@Shirley. I get what you are saying, and share some of your perspective. But I hope you'll listen to Dr. Reich (and Bernie and AOC, and others) - it is not the fault of individuals that they are left out of the economy! It is the operation of global capitalism combined with corporate greed and the role of money in our politics that ends up beating down workers, sending jobs overseas, and over-compensating CEOs and investors.

Yes Ben, I realize the truth of our situation. I was merely paraphrasing comments that were said by DT’s favorite poorly educated folks to Jordan Klepper. They were all about grievances & spouted them to anybody who would listen! The women interviewed were especially crazy sounding but gushed about loving Donald! Give me a break!! These interviews were sadly hilarious & should give anybody pause to be very worried about potential violence worse than we saw @ the Capitol!! I could definitely believe another insurrection from those crazy supporters happening any day forward!

Shirley you jest!

@Grrl. I believe exactly the same. I look at those trumpety voters with a combination of disgust and wonderment. But then I remember my ignorant, rebellious self at age 21 - I just wanted SOMETHING to be different...

Three major things we could do to help improve voters and voting would be: 1) Restore the teaching of civics in all public schools Nationwide beginning in at least the 4th grade. Although, it could begin as early as kindergarten by teaching children the benefits of sharing with and helping classmates and why bullying is not acceptable. 2) Get money out of politics first by making all electioneering financed by the Government, and second by limiting the time of electioneering to no more than 6 months prior to the election date. They might also consider more town hall type meetings, encouraging people to attend by offering refreshments or some form of entertainment. 3) Finally would be to get rid of the lobbyists.

All excellent ideas. A more informed electorate would be a check on the pervasive lies that are the currency of today’s politics.

We can get there only by electing sustained Democratic majorities in Congress and hopefully more AOC and E. Warren types. Representative Katie Porter in California's 47th District is another example of a hard working public servant who is not on the take!

WE seem to have a big problem with the establishment dems fighting progressives in our own party. pelosi and schumer talk the talk against republicans while they back neo-liberals and cuddle up to neo-conservatives..

@jesse. Part of that support for old line Democrats is a political calculation about who can win. No use backing a progressive in the primary only to see a Republican win the general election. But part of it is that our Democrats are too "establishment" precisely to attract people who shun progressivism but whose vote is needed to make up the majority party. sheesh, politics!

progressive candidates gave us the house and senate . progressives win against republicans. being given a choice between neo-conservative and neo-liberal is like choosing which cheek you want slapped. its time to try something new that makes the old way obsolete. stop turning cheeks and work around the corporate whores (whether the have a D or R next to their name). https://represent.us/the-strategy-to-end-corruption/

Yes! Personally, I vote progressive, then democrat if absolutely no other choice.

First by ignoring this very same self-defeating mantra, widely used among Democratic lawmakers. For us, mere citizens, I think the motto should be: If there is a democracy, fight for it! If there is no democracy, fight for it! The will of the people is the rule and the norm. It is our "why." "How" will always figure itself out from there.

The problem is my Trumpy adult kids are not 21 YOs, they are middled aged with families & just don’t use Critical thinking skills! My granddaughters in FL are much smarter than their Dad, they are in the early 20s & just graduated college. They see right through Rethug behavior & go with the Dems bec they don’t allow any religious views to color their opinions in Politics. I know they both voted for Hillary. The other 3 Voting age Grands don’t care to vote or particulate in Politics bec my guess is they don’t understand what’s so important & r so busy living there lives & working it’s the very last thing on their minds!

@Shirley. Interesting dynamics! But I will read in a hint - FL could go blue for a Bernie-type candidate who could pull from all parts of the generational divide!

You have my sympathy. The only solution I can see is long range. We need to go back to teaching civics in every public school in the country. It's not that I object to sports or physical education. It's just that I don't believe they should get priority in school spendi9ng over civics, science, and math. As a teacher for 18 years in a progressive State (California) I watched and complained in faculty meetings about this lopsided spending. At that time (70's through early 90's) the only required class for graduation was physical education - all other classes were at the choice of the student.

But he was a 'celebrity' for the downtrodden, that was enough. He spoke lies to them in a language they understood.

It doesn’t take much smart or savvy to pick up that Trump’s a loser. Bankrupting a casino!? The Mafia used to skim profits AND make money.

2016 gave us an election based on populism. The Democratic Party machine failed to recognize this and therefore failed their young, energized base by manipulating the polls that were leaning toward Sanders. If only they had “read the room” and countered the populist right (Trumpism) with the formidable populist Sanders, what kind of country would we be experiencing now?

The Democratic Party establishment continues to do this today. In a number of congressional primaries, they have put their thumbs on the side of old corporate fossils against energetic young progressives who really want to work to improve people's lives. Then they turn around and blame the progressives for their own failures in elections and policy-making.

Carolyn...You put you finger on it.

Our son was a huge Sanders supporter. After the Democrats buried Bernie alive our son quit voting. Sad but true. That happened to a lot of the young voters in the USA.

Bernie brought a lot of new people under his tent- the DNC burned the tent down. (twice)

It’s true. The energy was real because there was genuine hope for the return to a more equitable society. To the younger generation, this meant a breakthrough that would reign in the oligarchs and set the table for social and financial reform, a return to the vastly successful policies we saw under the FDR era.

Alas, the hope died when Trump, of ALL people, took the presidency. It died when McConnel successfully blocked Merrill Garland’s seat on the SCOTUS.

I know many that gave up, like your son. One really cannot blame them, but the ones that carried forth, more determined than ever, started organizing anew. The Sunrise Movement is a wonderful example of a youth-led activist campaign. Inspired by the teen climate hero, Greta Thunberg, these people are NOT giving up. So, in actuality, hope didn’t die after all, it is showing up in new ways, without relying on the founder of the modern progressive movement.

See AOC, Katie Porter, Cristina Tzintzun Ramirez, Stacy Abrahms and others.

Establishment Dems are an endangered species. They have failed us. Most are senile. Republicans are reactionary fascists. What next? I like Dr. Reich. He knows what must be done, but he knows the young must do it. Old guys like the Doc and myself can't do it

If the DNC had been following 538, they would have known Hillary was a particularly weak candidate for the 2016 election. There was vigorous polling throughout early 2015, and in hypothetical matchups between Trump and Hillary, and between Trump and Bernie, month after month, Bernie trounced Trump almost 2:1, while Hillary was about even with Trump.

Then Bernie was sandbagged, and Hillary became the official DNC nominee in the summer of 2015. It did not help that she had continued to take large paychecks from Wall Street, $225,000 for each speech, right up to the week she announced her candidacy. We all saw it, most of us were disgusted.

The roots of all (economic) evil are the massive tax cuts for the wealthy and the corporations, beginning with Reagan - a core violation of Smithian capitalism - continuing with W, and Trump. This enabled the rich to become super-rich and then to start seeding dark money into the political system (including, ahem, SCOTUS, which is SO political).

This bought more wealth and power, e.g., Pharma telling W that they should not have to play by those pesky Smithian rules about the marketplace, and could set prices, resulting in a quintupling of profits at the expense of the American middle class.

Biden can make a practical start by raising taxes substantially on those making over $400,000 a year.

I agree with your statements about the wealthy. The greed and love of power in too many politicians makes a joke of a democratic representative form of government. Too many voters rely on 30 second sound bytes instead of critical thinking

But it always was thus. Adam Smith knew that when everyone pursues their own self-interests there is inevitably going to be a tendency for the wealthiest to buy the favors of government and distort the market. Which is what we see in America today. His answer was strong government to raise taxes substantially on the wealthiest, thereby curbing their power. The taxes would be used to provide the average citizen with stuff the capitalists had little interest in - what we now call infrastructure - roads, bridges, canals, etc.

What did Reagan say? "Government is the problem." This was nothing more than code for "let's cut taxes on the wealthiest Americans." The result? Middle class anger, crumbling bridges and roads, etc.

Of course, Reagan was just reading a script he happened to agree with. In his simplistic view of the world, I believe he actually thought of himself as a cowboy, symbol of a free America.

Yes I remember reading Adam Smith's 'The Wealth of Nations' in my Economics classes in College. I absolutely agree that from Reagan through Trump we have enabled the wealthiest among us to gain total control. If they have their way, we will return to feudalism. a very few wealthy controlling the masses as slave labor. As I recall Smith wrote that book in 1776. He certainly had foresight.

@Fay - these issues began before Reagan. After the assassination of JFK and later the election of Nixon we began our downward spiral. Too many people simply were not paying attention to what was occurring. Today is the culmination of our own blind ignorance over the past 50+ years.

Although there will not be an immediate reversal, we need immediate action. We’re fortunate this is an election year. Maybe we can begin to turn the tides one election at a time.

You are right, of course, it was just more blatant with Reagan on. I especially like your comment, "Today is the culmination of our own blind ignorance over the past 50+ years." That is the crux of the matter, people who get starry eyed over celebrities, who pay more attention to sitcoms than news, ad nauseum.

@Michael. Reagan? Thought? Those two words don't go in the same paragraph! ;-D

LOL!!!

And you have to ask, if Hillary had become president, what would the corporations who paid her hundreds of thousands of dollars for speeches have received in return? Lax enforcement of laws? Opposition to lowering drug prices? General Republican lite policies?

Dr. Reich, please continue with your thoughts on how our current political system has been corrupted and FAILED us delivering the pathological lying narcissist Trump to the oval office and HOW the American people can take THEIR COUNTRY back.

Regarding Hillary, most people do not know or forgot that she sat on the Board of Directors at Walmart for a time. Someone in a Walmart board meeting shared that when the topic arose about raising workers' pay, all you heard from Hillary was "crickets". Just another corporatist. If she became president, you would have had TPP approved and who knows how many thousands better paying, middle class, U.S. jobs would be lost to other "cheap labor" countries. This is one reason I am so against "familial" politics. My solution, once one member of a family has been elected to office, at least two generations of that family must pass before another member can be elected. The Bushes and Clintons have demonstrated that the grift and dishonesty runs deep as their personal wealth grows enormously. Investigations after the Hillary's nomination was STOLEN from Sanders proved the DNC (Just as corrupted by Money and Power as the RNC) had rigged the nomination with help from Netflix Millionaire Obama. We desperately need a new third party that actually represents the majority of citizens, not just the billionaires. The DNC appears to be primarily focused on social issues and too timid to take the fight against Trump's RNC fascism. The January 6th investigation is a good start and MUST conclude with a strong DOJ that will INDICT THE LEADERS OF THIS CONSPIRACY! NO PARDONS. Mandatory PRISON SENTENCES. UNLIKE when the Democrats did NOT hold Wall Street accountable for their shenanigans from the Great Recession. JP Morgan, a PUBLICLY HELD COMPANY, CONVICTED of metals manipulation and fined $920 MILLION, yet how is their CEO, Jaime Dimon, still allowed to hold that position??

The process and selection of U.S. Supreme Court justices MUST be investigated for corruption as well. TERM LIMITS are necessary to help limit the corruption. Thoroughly investigate the religious extremist Leonard Leo and the dark money and shell companies that have purchased the current "supreme" court majority. We need INDICTMENTS!! Without INDICTMENTS, more and more Americans, will continue to believe that they no longer have any say in how "their" government is run and they are merely "new age slaves" to their corporate masters and their job is to do as they are told, even to the point of relinquishing their own body to the whims of their government Master. This seems to be the current Republican version of FREEDOM.

Of course......in addition to more spending on the military and more foreign wars.

@Michael. If only he could. But it takes legislation...

Benjamin, I agree, it would have been threading a needle.

But if I recall correctly, the needle was almost threaded, and higher taxes were part of BBB. We could have had almost $2 trillion courtesy of Joe Manchin, if only we had given him a little bit of coal. But, the perfect turned out to be the enemy of the good, and we came away with nothing. This bothers me immensely.

I thought Bernie could easily have beaten Trump in 2016, but I have to wonder if, in his stubborn pursuit of purity, he simply doesn't know how to compromise.

I am supportive of GND but not at the expense of maintaining a low tax rate. The world is already on a glidepath to renewable energy, EVs, etc., with or without GND legislation.

Thoughtful...

Bernie appeared on a Fox Town Hall and won a standing ovation. He could have beat Trump, but the neo-liberal Dems and their Wall Street backers wanted Hillary, a neo-liberal chicken-hawk who never saw a war she wouldn't vote for and blamed 9/11 on Canada's supposedly laxer security.

@Maureen. But also, too many people like me who didn't think Bernie could win, or that if he did win he couldn't govern. I regret my mistake.

That's sad. I know a lot of people felt like that, but when I saw him get that standing ovation at the Fox Town Hall--to the obvious consternation of the Fox hosts--I really thought he could win back many of the disaffected former Dems and keep many of the current ones.

As for governing, my cat could have done a better job than Trump, and she wouldn't have tried to overthrow the government.

I also appreciate Bernie's willingness to appear on Fox and write op-eds for their readers. He is principled and fearless and will not back down. And he's always polite but firm, no histrionics. And of course, what he's saying makes way too much sense!

I feel the same.

I was an independent in 2016 and would have voted for Bernie in a heartbeat, but neither would I vote for either Clinton or Trump.

Great summary and observations, Robert. If only my Republican hard nosed relatives would expose themselves to your column here! I lose hope!

Keep on plugging. We can get past relatives and work to enhance the big picture.

Stupid is as stupid does.

I send it to mine everyday!

Thank you, Dr. Reich, for explaining so eloquently what I've thought and said since 2000. I was so excited reading Barack Obama"s the 'Audaciousness of Hope'. I thought, finally, a politician who understands and will make changes. Had it not been for McConnell's determination that no meaningful legislation will pass, and the lack of courage of too many Democrats in Congress, we might have had real changes. But greed and addiction to power won.

It’s a shame (and a threat to our democracy) that most Republicans don’t realize Trump is the very thing he claimed to be fighting against, as well as many other bad things, but I digress.

That's the Art of the Deal, isn't it?

@Philippe. But the book didn't reveal the real "art" which is to deceive, lie, misdirect and blame others. Circus magicians got nothin on old bone spur...

The deception is that Trump did not write the book, as it was to say, later, that he would drain the swamp.

@Philippe. Exactly. I actually studied with Michael Gordon, the man who actually wrote Entrepreneurship 101. Dr. Gordon reported that Trump wouldn't even read the drafts and didn't even write his own introduction!!

Thank you.

Thank you for your clarity and conciseness. However you keep skipping the fact that over 44 million of us are in student loan hell. I am a doctor and I am more economically insecure than ever. As Alan Collinge, the head of Student Loan Justice, has stated we would have been better off losing hundreds of thousands in Las Vegas where we would have had bankruptcy protection. Please start bringing this issue to the forefront more.

Student loan hell is a big part of that rigged system. Loan purveyors bought themselves some protections in Congress.

So insightful! The people were not wrong to say Hillary Clinton was part of the Establishment - so much so that she could manipulate people into illegal behavior during her primary campaign against Bernie. Too bad the Establishment Dems were so blind that they could not see that Bernie would have been a great president, bringing the US into the 21st century, instead of being hurled back into the Dark Ages by Trump and cronies.

The thing is, establishment democrats would not be establishment democrats if they stopped courting their donors and fought, like Bernie, for the common good. What they have in mind is "The Third Way," i.e. the end of politics as a necessary debating space. As James Carville said, "It's the economy, stupid!" In their perspective, money speaks, people less so. The country is now paying in a terrible way for this lack of vision.

I keep a vivid memory of two Trump voters with whom I had a discussion in the early days of the 2016 presidential campaign. They were nothing like the caricature of hatred-filled cult followers we see today. What stroke me, aside from their personal gentleness, was their total absence of political awareness. They were for Trump with no other justification than he is a big mouth. They did not say it this way but this is what they were expressing. He is a big mouth, so he will put an end to the rigged system in Washington. To my dismay, I could see through these two very decent people how entire populations had been caught under the spell of Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. Demagogues offer us the opportunity to stop thinking. For many, it can seem a relief. Since the situation is so bad and the solution so far above them, or so it seems, the psychological trap they fall into is to accept the license handed down to them by the dear leader to stop being responsible entirely.

The antidote for your friends is probably benefits, because they don't sound like cultists.

99% lost deductions due to the 2017 tax cuts.

Maybe. I lost touch with them since then.

@Philippe. Very good analysis, explains part of the problem statement. Trump supporters are a coalition of disgruntled, so there are at least several, perhaps many explanations that each express the motivations of a part of that coalition. A risk for secular, rational government is that if the next demagogue can pull in just one other disgruntled demographic that coalition may attract (instead of 38%) 45% or more of the electorate and give the whole government over to the moneyed interests and their fascistic running dogs.

DeSantis?

@jim. Exactly what we are trying to prevent!

And so the democratic party was rigged against a candidate who had the best chance of beating Trump and we have been paying the price since. As long as the underlying economic anxiety is not addressed by this party, I agree, the conditions exist for the emergence of an authoritarian government.

Best summary of what I agree happened and is yet unaddressed. As odious as the Republicans are, unfortunately the Democrats (which I have always aligned with happily) seem clueless and part of this system. I think Biden gets it but as a politician he cannot act. Unless they wake up, the system may have to fail first in order to recover.

I think Biden is good in certain ways, but he embraces old, cruel, dangerous policies—drone wars, deportation of immigrants, and refusal to support the good leftist governments south of the border. Just to name a few things. Free all the whistleblowers—Assange, for instance.

What r u referring to by saying “ the system?”

I would say the closed system of money in politics. That must be defeated first, then politics will find back its own legitimate space and people will have a chance to be part of the picture. No money in politics means the restoration of genuine democracy and far less ground for a demagogue to channel anger and frustration.

For a better understanding of money in politics and its legal structure/system: https://www.levernews.com/roberts-is-the-man-behind-the-curtain/

What makes you think it will recover?

I am an optimist, and I believe that human history has generally moved towards positive ends. We may be witnessing the initial points of failure now.

I hope you're right--but sometimes, like after the fall of Rome, the recovery can take several centuries.

I agree, but the "dark ages" were dark for former Roman territory. In Europe, Spain was a bright spot under the Moorish influence, which established great Universities, libraries, etc., but I agree the rest of the world (Asia, the Americas, and Africa) may not have fared well.

Not this time. Technology is one reason, plus some lessons learned.

Given the state of the US these days, I'm not so sure about "lessons learned" (remember when Susan Collins voted not to impeach Trump because she thought he'd "learned his lesson"?) However, though the collapse of the US would have drastic repercussions world-wide, the US, unlike Rome, is not the sole center of civilization for the Western world. Perhaps Europe would help out with reconstruction via a reverse Marshall Plan, and, likely, Canada, Japan, and some Latin American countries would help out.

@Carol. Yes, the assholes have learned some important lessons on how to cheat us all and hide behind lies...

Yes, you are spot on!

Good answer! Thank you.

The only way out is to register more democratic voters and run on rebalancing the court and communicating plans to restore what the middle class has lost to the Trump United Fascist Party(TUF)

Field Team 6 has a database Contact: Mervis Reissig merv4peace@gmail.com

https://www.fieldteam6.org/

If Bernie Sanders was up for vote, way more of my family would have showed up to the polls. They said they didn't want either Trump nor Hillary so they didn't vote. They didn't feel either candidate was someone that represent them. Sad but that's how it was.

There's far too much to unpack here, and delving back to the contentious 2016 election, and rehashing the Sanders-Clinton battle only rubs the raw nerves of those differences. Had Sanders played his hand better, rather than blame everybody and everything but his own weaknesses as a candidate, maybe he could have done better against Hillary. He would never have beaten trump anyway. He was a weaker candidate than Hillary. After all, he lost the primary by a large margin to her. As for the Democrats "tipping the scales for Clinton" that's hugely debatable, but if true, then, it would prove two things. The Party is far more powerful than I thought, and secondly, it was way better at doing the job that a political party is designed to do. The statement there's something inherently wrong with "tipping the scales" to see that the party's chosen candidate wins a primary is ludicrous since that's supposed to be the main job of a political party. Sore losers never look good. I give you donald j trump, the sorest of all losers in history. If Democrats can't all join together and work as one, not only is the party doomed but so is our country. We must find and elevate a great candidate in the mold of JFK. The Democratic Party has been in charge of the country for going on two years, yet nothing has gotten done. I'd say, we've gone backwards. We must learn to play the game better. Repubs are playing circles around us. That is a BIG problem!

Bernie isn’t weak. He deserves more support.

Reread. I didn't say he was weak. I said he has serious weaknesses.

I think tRump lifted some of Bernie's best talking points, about the system being rigged and the idea of bringing back jobs to American workers. The Socialist label is anathema to this day, and it was used against Bernie in the few comments the media carried. He did not get the coverage that Hillary and tRump got, for sure. even when Bernie was winning, the nervousness of Wall street and the establishment was there. He was a threat to the oligarchs, and all those who thrive on our 'investment' economy.

What everyone, including Mr. Reich, have left out of all of this equation is older, highly educated, individuals. We are STILL being left out of EVERY SINGLE CONVERSATION. We simply do not exist in the minds of anyone who is controlling the narrative. Age discrimination is real, rampant, and continues to be left unchecked. When the Great Recession (which was really a depression) hit, many of us lost everything. Thousands of us never made it back. We lost professional licenses because we couldn't keep up with the payments and the continuing education classes. We filled out thousands of applications and went on hundreds of interviews. We continue to be ignored. We did everything right. We took out student loan debt (another gordian knot issue in and of itself), began at the bottom, sacrificed, etc., everything we were told to do. No one, NO ONE, ever paid attention to us, and we still are invisible. We are tired, angry, and broke. We know the systems are broken because we watched them being dismantled right before our eyes. We were and continue to be the fodder of the systems demises

@Denise. You illuminate what makes me so mad at Jerome Powell (and Joe Biden for leaving him in there) - the main effect of a recession or a depression is just another way of transferring wealth from wage earners to the rentier class (wealthy and oligarchic moneyed interests). Thank you for your illuminating perspective!

Sanders should have taken the Democratic presidential candidacy & he would have won in 2016. Life in USA would be very different. But the establishment, Clinton too consumed with being the first woman president and the power that she would have. As Secretary of State, she has abused her power, arming foreign countries. She owns the DNC, so it is only natural that she would have been the candidate. Trump and the Clintons are connected as all of the corporate dems are with the oligarchy. Its a game in Washington and as a middle class healthcare professional I am very tired of all the bullshit. People want to see action. What happened January 6th should have been dealt with right away showing the American people that we are not going to stand for this. But no the democrats take a passive response...oh we don't want to cause more uprising, well how are we doing???? Berne is an independent. He has been consistent with his messages through his tenure. He has done more for the working people in the past months than any of the corporate Democrats have done in the past 50+ years. I am so tired of the passiveness of the democrats. What the Republicans have is a voice and a consistent theme and goal. I don't like it but it shows that they know what they want and they are gong to go for it, legally or illegally. It is very sad. Media doesn't tell us what we need to hear it tells us what it wants us to hear. I appreciate your messages and information. Keep it coming :) Rachel

The last few sentances of your post today, Mr. Reich, are the most important for politicians to hear, in my humble opinion, particularly this: "...in the 2016 primaries, Bernie Sanders did far better than Clinton with blue-collar voters. He did this by attacking trade agreements, Wall Street greed, income inequality, and big money in politics." This is the messaging Democrats need to employ, I think, if they want to win back the Senate and keep the House....

An oft-quoted remark of Justice Brandeis is, in essence: We can have great inequality of wealth and income or we can have democracy, but we can't have both.

There it is pure and simple.

Illuminating! You just reminded me of myself at 21, fresh out of the army, a bit early on a "return to school" waiver. I'll be forever humiliated to admit I voted for George Wallace in 1968 (!). But I did it for exactly the same reasons and perspectives as you enumerated here. Paraphrasing Wallace: Democrats and Republicans? There is not a dime's worth of difference between them! The homespun language, the anti-establishment stance and the revolutionary rhetoric made me overlook the overt racism and other notable defects in Wallace's platform. Perhaps luckily in Wallace's case, and like what happened to Bernie, the institutional parties ensured Wallace's candidacy couldn't succeed. I went on to get educated and have voted reliably Democratic since, in spite of flawed candidates the party sponsored. Now, 54 years later, I don't mind asking: Republicans in Congress? Democrats in Congress? Is there more than a dime's worth of difference between them?

@Leynia. I wrote that hoping someone would come to the defense of the Democrats. There is a difference, just not enough of a difference when you have so-called Democrats like Manchin and Senema who vote Republican too often and where progressives like AOC and activists like Bernie are in the minority of the party. Democrats are perhaps redeemable AND they are the only chance we have in the midterm elections.

Unfortunately they are still backing establishment democrats instead of progressives in the primaries.

I agree completely. I am now a disillusioned life long Dem. The candidates I have contributed to have sold my address and now I am so deluged with begging requests that I have started unsubscribing to all political except R. Reich. But if they ask reason why, I take time to say the Democratic National Committee was 'playing politics' too long and when they sabotaged Bernie it is now coming home to bite them. I am 78 but still think Bernie and AOC and all Progressives have their heads on straight. Biden goofed majorly by not even inviting Stacy or Bernie or other truth tellers to be on his Team so he wouldn't lose the youth and Black numbers. We don't want safe white men, middle of roaders, beyond-senior age lawmakers - not while the world is burning and the US is locked in a pissing contest over which party is best. All those distracting 'issues' will mean nothing compared to climate reality getting worse.

For some strange reason, I found Professor Reich's description of Bernie Sanders as a 74-year-old Jew to be very offensive. It may be because Bernie was not campaigning as a 74-year-old Jew but as a progressive, democratic socialist with a consistent message and a solid background in public office. What did his age or his faith have to do with his competence and his ideas and plans and policies? I sure didn't think about it then and I don't think about it now. I support Bernie whole-heartedly and for what I believe are the right reasons: he is concerned about ordinary people trying to live ordinary lives and those are also the concerns of 34-year-old Hindus...Would Bernie have governed as a 74-year-old Jew if he had won the presidency? How does a 74-year-old Jew govern? What people elected was a 70-year-old egomaniac who has no particular religious affiliation (I have never thought of Trump in terms of religion). How did that work out? The root of most of our problem with attempting to govern ourselves is the lack of the most basic education and experience with history, civics, public service. Somehow we decided that education didn't matter (I think Reagan was a proponent of the a-historical approach) and that's where we've landed. In sum: our problem is our lack of education and general knowledge, not that some of us are 74-year-old Jews...that may be the defining characteristics of Reich's view of Bernie Sanders; they are way, way down the list as far as I'm concerned. (You might note that a 45-year-old Jew is now President of Ukraine but his defining characteristics are educated, personal charism, competence, experience, leadership ability, and a deep love of his country...too bad we have not chosen as carefully as the Ukrainians.)

@Lanae. I believe Dr. Reich was trying for a contrast to those who looked at Bernie as a 74 year old jew when Bernie was obviously what you said, a progressive American. By the way - do you follow science? Astronomers say there is a new object on Earth, never seen before, but that it is now visible from space.

Zelinskiiy's balls....

I agree with the most of this article, however I will point ourt that the Democrats lost 10 iof thousands of votes when they pulled a little trump trick themselves as you mentioned. "Had the Democratic National Committee not tipped the scales against him, I’m convinced Sanders would have been the Democratic Party’s nominee." What make the two parties any different? Much could have been accomplishesd for the middle class and labor when Obama had the majority of all. Very little was done in my opinion. Perhaps we do need a Working Class Party.

Check out the Working Families Party.

https://workingfamilies.org/

A further note on lobbyists: There is a revolving door in Washington DC whereby "players" i.e. politicians who lose their elections and cabinet members or political employees leaving their jobs are swooped into the lobbying cabal. These insiders know the movers and shakers in DC so they have a step up on who to bribe and the most effective bribe to use. For some it is forming a PAC to finAnce their re-election campaigns, for others it is cushy jobs for their family members, for the lowest of the low, like Matt Gaetz, it is offering sexual partners. These lobbyists are parasites who offer no worthy purpose for society as a whole, I believe it would take a huge uprising of the electorate to get rid of them. I don't think passing a law would do the trick.