Last Sunday night, as cryptocurrency prices plummeted, Celsius Network — an experimental cryptocurrency bank with more than one million customers that has emerged as a leader in the murky world of decentralized finance, or DeFi — announced it was freezing withdrawals “due to extreme market conditions.”

Earlier this week, Bitcoin dropped 15 percent over 24 hours to its lowest value since December 2020, and Ether, the second-most valuable cryptocurrency, fell about 16 percent. Last month, TerraUSD, a stablecoin — a system that was supposed to perform a lot like a conventional bank account but was backed only by a cryptocurrency called Luna — collapsed, losing 97 percent of its value in just 24 hours, apparently destroying some investors’ life savings. The implosion helped trigger a crypto meltdown that erased $300 billion in value across the market.

These crypto crashes have fueled worries that the complex and murky crypto banking and lending projects known as DeFi are on the brink of ruin.

Eighty nine years ago today the Banking Act of 1933 — also known as the Glass-Steagall Act — was signed into law by Franklin D. Roosevelt. It separated commercial banking from investment banking — Main Street from Wall Street — in order to protect people who entrusted their savings to commercial banks from having their money gambled away. Glass-Steagall’s larger purpose was to put an end to the giant Ponzi scheme that had overtaken the American economy in the 1920s and led to the Great Crash of 1929.

Americans had been getting rich by speculating on shares of stock and various sorts of exotica (roughly analogous to crypto) as other investors followed them into these risky assets — pushing their values ever upwards. But at some point Ponzi schemes topple of their own weight. When the toppling occurred in 1929, it plunged the nation and the world into a Great Depression. The Glass-Steagall Act was a means of restoring stability.

It takes a full generation to forget a financial trauma and allow forces that caused it to repeat their havoc.

By the mid-1980s, as the stock market soared, speculators noticed they could make lots more money if they could gamble with other people’s money, as speculators did in the 1920s. They pushed Congress to deregulate Wall Street, arguing that the United States financial sector would otherwise lose its competitive standing relative to other financial centers around the world.

In 1999, after Sandy Weill’s Travelers Insurance Company merged with with Citicorp, and Weill personally lobbied Clinton (and Clinton’s Treasury secretary Robert Rubin), Clinton and Congress agreed to ditch what remained of Glass-Steagall. Supporters hailed the move as a long-overdue demise of a Depression-era relic. Critics (including yours truly) predicted it would release a monster. The critics were proven correct. With Glass-Steagall’s repeal, the American economy once again became a betting parlor. (Not incidentally, shortly after Glass-Steagall was repealed, Sandy Weill recruited Robert Rubin to be chair of Citigroup’s executive committee and, briefly, chair of its board of directors.)

Inevitably, Wall Street suffered another near-death experience from excessive gambling. Its Ponzi schemes began toppling in 2008, just as they had in 1929. The difference was that the U.S. government bailed out the biggest banks and financial institutions, with the result that the Great Recession of 2008-09 wasn’t nearly as bad as the Great Depression of the 1930s. Still, millions of Americans lost their jobs, their savings, and their homes (and not a single banking executive went to jail). In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, a new but watered-down version of Glass-Steagall was enacted — the Dodd-Frank Act — which has been further diluted and defanged by Wall Street lobbyists.

Which brings us — 89 years to the day after Glass-Steagall was enacted — to the crypto crash.

The current chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission, Gary Gensler, has described cryptocurrency investments as “rife with fraud, scams, and abuse.” Yet in the murky world of crypto DeFi, it’s hard to understand who provides money for loans, where the money flows, or how easy it is to trigger currency meltdowns. There are no standards for issues of custody, risk management, or capital reserves. There are no transparency requirements. Investors often don’t know how their money is being handled or who the counter-parties are. Deposits are not insured. We’re back to the Wild West finances of the 1920s.

In the past, cryptocurrencies kept rising by attracting an ever-growing range of investors and some big Wall Street money, along with celebrity endorsements. But, as I said, all Ponzi schemes topple eventually. And it looks like crypto is now toppling.

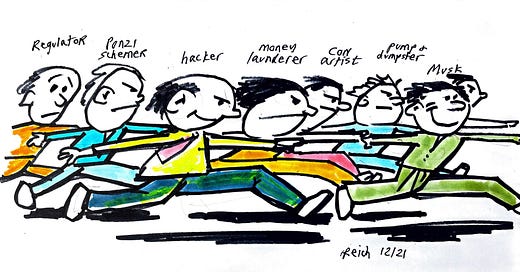

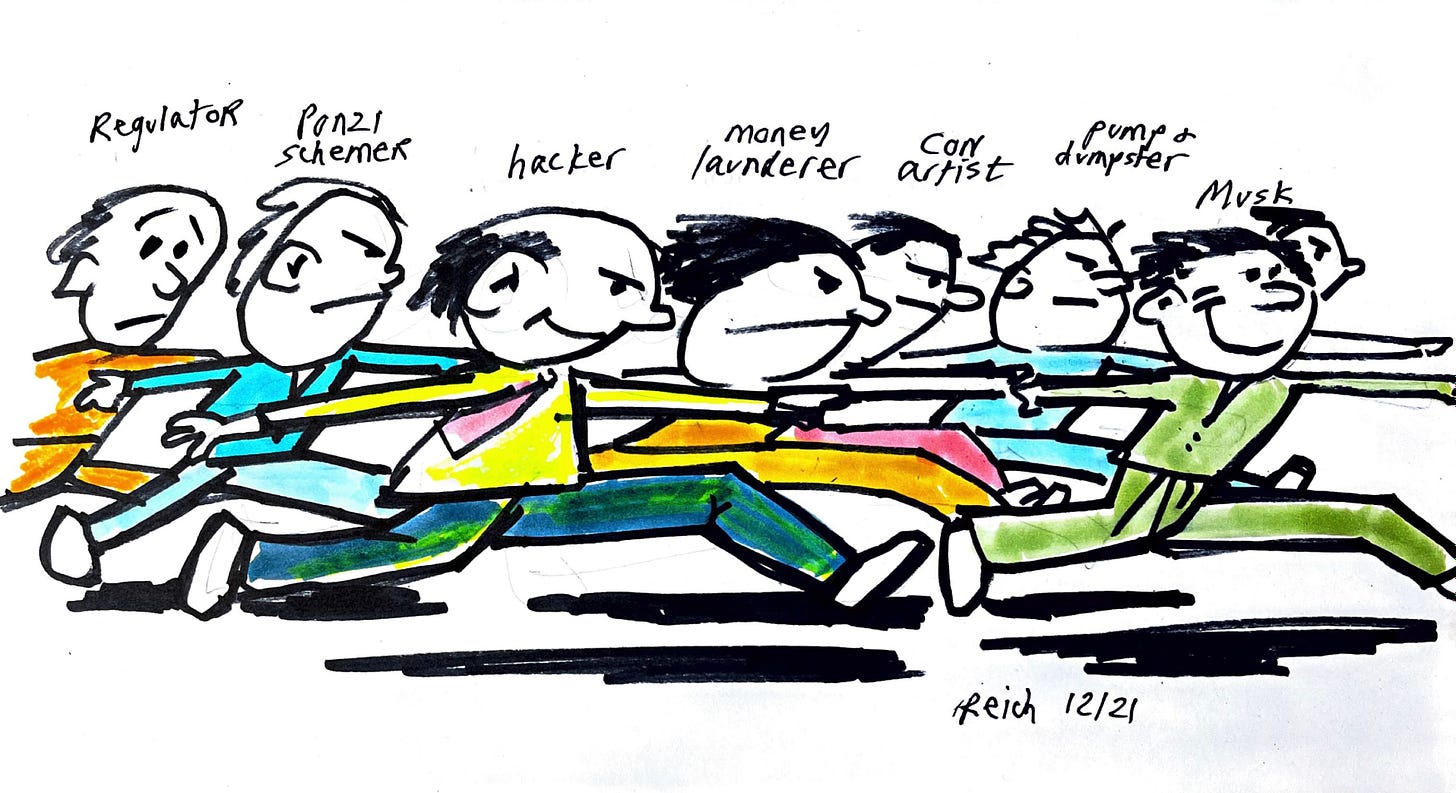

So why isn’t this market regulated? Mainly because of intensive lobbying by the crypto industry, whose kingpins want the Ponzi scheme to continue. The industry is pouring huge money into political campaigns. And it has hired scores of former government officials and regulators to lobby on its behalf — including three former chairs of the Securities and Exchange Commission, three former chairs of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, three former U.S. senators, and at least one former White House chief of staff, the former chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and more than 200 former staffers of federal agencies, congressional offices and national political campaigns who have worked in crypto. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers advises crypto investment firm Digital Currency Group Inc. and sits on the board of Block Inc., a financial-technology firm that is investing in cryptocurrency-payments systems.

In a famous passage from his 1955 book The Great Crash 1929, my mentor, Harvard professor John Kenneth Galbraith, introduced the term “bezzle” (derived from embezzlement). Galbraith observed that the bezzle in a financial system grows whenever people are confident about the economy, and reveals itself when confidence ebbs:

At any given time there exists an inventory of undiscovered embezzlement which … varies in size with the business cycle. In good times, people are relaxed, trusting, and money is plentiful. But even though money is plentiful, there are always many people who need more. Under these circumstances, the rate of embezzlement grows, the rate of discovery falls off, and the bezzle increases rapidly. In depression, all this is reversed. Money is watched with a narrow, suspicious eye. The man who handles it is assumed to be dishonest until he proves himself otherwise. Audits are penetrating and meticulous. Commercial morality is enormously improved. The bezzle shrinks.

Crypto is pure bezzle — as is now being revealed. If we should have learned anything from the crashes of 1929 and 2008, it’s that regulation of financial markets is essential. Otherwise they turn into Ponzi schemes filled with bezzle — leaving small investors with nothing and endangering the entire economy. It’s time for the Biden administration and Congress to stop the crypto bezzle.

What do you think?

I told a friend who was investing in it and trying to get me to invest that it was a ponzi scheme. After 35 yrs in Finance & losing my job when Sandy took over Citibank I knew garbage when I saw it. Making money with a computer program, oh yea, sure. Now why is the Fed trying to cause a recession & make middle class people lose their jobs instead of going after the companies that are price gouging. How will mass layoffs bring down the price of a pkg of hamburger meat? The rich don't like it when the middle class gets ahead so they have to price gouge and force recession. This is pure bs.

Whenever something like this is happening, the question is who are the ;losers and who are the winners.

Losers who were marks have to come forward. "By Tuesday, Celsius hired attorneys to explore a financial restructuring, the Wall Street Journal reported. Fear of systemic risk drove the value of the cryptocurrency market down, now holding below $1 trillion."

"According to its website, Celsius has 1.7 million users. It offers users a very high annual percentage yield (APY)—advertising up to 18.63% APY just yesterday—to deposit their cryptocurrency on its platform. Users can also borrow funds from Celsius so long as they offer other cryptocurrency as collateral for their loans. When investors cannot reach their margin requirement, their position gets liquidated."

Who are the 1.7 million losers? Did they think they were insured? Other "banks" (E.G. FDIC} are covered even if they are only state chartered. The whole enterprise may/may not have been a scam.

Winners need to be identified. Brokers? Is there a "short" market comprised of speculators who bet against Celsius?

If "restructuring" means bankruptcy, I hope a US trustee is involved.

BTW, those 1.7 million losers should be advocates for regulation. Wonder how many are registered Republicans?

You wonder how many of those 7.5 million were retirees trying to stretch their retirement income, acting with their backs against the wall.

I think it is more about the Sirens Call and Odysseus than Republicans and Democrats. The younger you are, the louder the call. . . sex or money.

David Richardson. Follow the data.

IMHO young Republicans more susceptible.

I know some kids who sold them to elderly parents. One ad here in Baghdad By the Sea was telling people to convert their IRAs, 401Ks. Offered more than 10%. interest My parents invested in Mexican pesos when they were getting 20%+ bank interest. The peso crashed. All they got were deductions for losses for about 20 years. That was an object lesson for me. But I had an uncle who put some of his money in a CD that was paying a high rate in a savings and loan was burned during the savings and loan scandal.

Not talking about the general population. These people were screwed.

Three card monte. Step up to the table. Marks out life savings in some cases.

Even the cons need religion. Most effective evangelists. Judges at sentence hearings.

Once marks see the cons are "outed" they flip.

The big haul in three-card-Monte isn’t the buck or two the trickster swipes. It’s the trickster’s pals who size up the looky-loos in the crowd, watching the trickster at work. They lift a dozen billfolds for every buck the trickster lifts. Sweet swindle, eh?

@ppp - I have never been able to wrap my head around Bitcoin or cryptocurrency. If I cannot hold a dollar that I can deposit in my bank (or my mattress) then… I won’t.

Public Service digression:

For any of you who don't know,

JIC you missed it and are interested: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/watch-jan-6-committee-hearings-day-2

(PLEASE NOTE: The previous video announces that the 3rd hearing was supposed to take place yesterday. That hearing was cancelled for some reason and rescheduled for today 6/16/22)

Today's hearing starts a 1:00 PM EDT at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/how-to-watch-the-jan-6-hearings (At the video link here, you can see today's hearing.)

https://january6th.house.gov/

You & I are of the same mind on that.

You know what they say Jaime: “Great minds…” 🌻

Amen. The stock market is enough of a gamble.

The wealthy aren't gambling in the stock market; they are manipulating it, for which see Elon Musk's boast. Only those with middle income means are "playing" the stock market. The poor are sidelined, as the middle class gets progressively (!) pulled under. More regulation is needed to protect us all.

So very true.

Especially the oil companies. They don't care who they hurt.

Totally! Chris Krebs said a long time ago that it is also a huge national security risk because hidden, shadow bad actors in foreign countries (and ours) use it. Of course our government should put a stop to it. But our government can't pull back the corporations causing inflation and address the real reason we have it. These damn Democrats are neo-liberalists. Their solution to inflation is what the ruling class wants because it further weakens the American worker and citizen. The rich can take more, get richer, after all, that's what's happening, isn't it? Cryptocurrency is a rich man's game. I always knew we were screwed when Larry Summers was giving Biden advice. Biden is the Obama presidency with the country in the crisis of our lives caught between new-liberal and new fascists annihilating the country from within. There is no one to stop it. I have talked to friends, in my generation, and everyone is scared and horrified at what is happening here. Everyone. We will be fortunate if what's coming now is ONLY a recession. The Democratic party needed to get this right but they are beholden to their donor class and Biden to bipartisanship.

agree!

How strange. I wrote a comment that was going against this massive echo chamber and it got deleted. I was pointing out the numerous flaws and misleading assumptions in this article, but I guess Robert Reich only wants to surround himself with people of the same opinion. Strange because I've learned that this is not how you grow and learn.....

Oh well, have fun staying oblivious to the other side of the medal

thank you for a wonderfully educational piece. i have long been suspicious of crypto currency, thinking it was a ponzi scheme because i had no idea where the money came from, where it went and anything else about it. it's nice to learn from a real economist that i was right to trust my instincts.

Such flattery and another nice tribute to Professor Reich. My sentiments exactly. 🌻

Admittedly I have yet to understand itcoing and crypto currency. However the technology behind the Ponzi scheme can prove to be very beneficial. The true benefit is transparency. While I won’t be investing my life savings(jk there’s no such fund,won’t ever be😅) in crypto, I do believe blockchain technology helps us as a society get closer to our common goals. Imagine if we didn’t have to guess which congress members are receiving their cuts from the NRA in order to keep guns in circulation? If we had transparency would McDonald’s have been able to make mcmillions for themselves off their own monopoly game? All the money everyone made during the pandemic? Furthermore, if your finances were transparent as well, let’s say instead of your bank being able to loan out your money as their “own for profits”, you are able to see where your money is going and you’re the one to benefit if it is loaned out?...while I’m not placing all my eggs in the crypto basket, the technologies behind the concepts of blockchain and smart contracts can prove to be very useful.....I think.

Bill Maher recently said he doesn’t understand crypto on his program and essentially said, nobody can explain to him how it works. Mr. Reich you should call him and ask to be on his program. You could explain it to him.

>OUTSTANDING SUGGESTION!<

YES

This is a wonderful piece, insightful, informative, fun, important. And thank you for reminding us of the great John Kenneth Galbraith and his wonderful term "bezzle"!

Well said, Adam 🌻

Yes, I have suspected since I first heard of it that 'crypto' was a huge scam. But, for some reaon - greed, I think- some people always fall for get rich quick schemes. The Republican Party has favored 'open market' and deregulation. I hope to hell, the Democrats won't fall for that "too big to fail" crap again. The only time I ever questioned Obama's integrity was when he agreed to bail out Wall Street. We need Glass Steagle again. Only this time it should be really hard to undo. Besides insider trading the other scheme that needs to be criminalized, is buying short where you put in 10 % , then use other people's money to purchase at a 'low price', sell high and "make bundle".

Revival of GLASS-STEAGALL long overdue. But not possible in this "captured" climate. Sad.

I agree with you on Obama. People lost; banks won.

@Faye. The first in stand to make a lot of money. Then the next crowd thinks "it's still early, I can make a lot of money" then the average guy on the street says "those people made a lot of money, maybe I can get in on this..." that last step is where it tips over, but the early folks (and the inventors) still made a lot of money, taken directly from the pocketbooks of the average guy on the street. Ponzi inventors all know that their scheme will tip over - that's why they take money out at an early opportunity.

Is that why Elon musk cashed out his Tesla Stock? With an IPO of $22.00 and a 5 for one stock split, Telsa Stock is up 18,000% for a company barely making a profit. Elon is pushing "DOGECOINS" as his next big thing and because Tesla is up 18,000% then DOGECOINS will climb also. The Ponzi scheme was named after a guy named Ponzi so Tesla and DOGECOINS will be the "Musk scheme". If it seems too good to be true...

Zactly

Totally correct. It was all evident from Day One. By 2018 some London builders who were working in my house were bragging about how much they had made in Bitcoin. Ordinary men who usually believe in bricks and mortar and their own solid practical skills. Such scams corrupt all moral sense.

I've >never< met a compulsive gambler that ever did anything but brag about how much they won on the lotto, the casino, or whatever. I've >never< heard a peep out of 'em on how much they lost at the end of the day.

Exactly. Gambling, including state lotteries, produces nothing of value and sucks huge amounts of capital out of communities that need every bit of investment they can get, selling nothing but false hope. The same for crypto: it produces nothing. Likewise the Ponzi schemes that threatened in 2008.

When will humans learn that only producing something that encouraging human flourishing - food, clothing, shelter, health care, community, education, social services - OK, also entertainment, which also creates community! - is worth investing in?

Profound truth

The German Philosopher, Friedrich Hegel, said:

"We learn from history that we do not learn from history."

In this moment we find ourselves, we must prove him wrong, at least for once.

"There's a sucker born every minute....."

How many Trumpers were losers in crypto? Is there a correlation?

Please Wall Street is controlled by American Oligarchs, look at what Musk did to twitter and its stock! The regular everyday American is controlled by the very few, iie: NRA, Big Oil. I am more concerned about their manipulation of the Stock Market then I am of Crypto. I suggest you look up what a Ponzi Scheme is and look at the Real Estate bubble that is happening again with housing that is inflated.

And the "student loan backed securities" that seem like they were created almost entirely to drive up student loan rates and tie the rest of the economy back into the con, so certainly someone is out there arguing that forgiving student loans will hurt the economy... only in so much as they packaged them into toxic asset packages again and pawned them off on institutional investors, just like with the 2008 mortgage backed securities.

Wall Street's ability to innovate new dysfunctional grifts apparently has no limit, and no self awareness that they are building the same house of cards over and over again with a different deck. Imagine if any of these people used their keen intellect for anything that actually improved society.

In the absence of wisdom, discipline, and self awareness on Wall Street, regulation is needed to stamp down on some of these pipedreams *before* they are turned loose to ruin everyone else's long term economic prospects.

Lucille. Got to see what short sellers like Bill Gates did to Tesla and Twitter stock.

I commented below on Sarbanes/Oxley and Dodd/Frank which should be extended to every market.

"Wall Street" is regulated in the main by the SEC. FTC, Commodity Futures, etc. I heard Sarbanes/Oxley Dodd/ Frank whistleblower cases. The SEC has a bounty program for people who turn in wrongdoing. https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2021-177

Also most people don't know that speculators are betting against the market and against stocks and bonds. A puts and calls market exists to even cover future value.

IMHO lobbying is legalized bribery and needs to be criminalized. Markets are a form of gambling, subject to scams.

"Lobbying is legalized bribery." Guess that's why John McCain called it "corruption" when he was campaigning against GWB for the Rep nomination to run for President on the Republican ticket. I changed my registration to Republican so that my vote would count for him, while asking my ancestors to forgive the vote cast out of necessity.

Bandits can always be heard, “We don’t need no stinking [regulations]!”

yes ; remember the Texas energy grid failing in a cold snap not too long ago? They did not want regulation to require investments that would protect against the massive failure of the grid in a deep freeze. Some people died.

And people will die in the heat waves. In Texas this week, the (untruthfully) much-maligned wind and solar sources keep pouring out the KWH, much to the chagrin of those who feed off people's misery in that designed-to-fail grid "system."

I think you are spot on Robert. I have been saying the same. JKG is one of my heroes and his observation on the bezzle also spot on. Interesting if you read the “Pecora Report” and distil the risks it reveals, you find they are cryptos risks today. As I keep on saying there is nothing new here. Great column keep up the great writing. JAS.

Yes! Enter Liz Warren!!!!!!!

They must stop all money flowing into government by lobbyists.

I once read a report by anthropologists that found evidence for a prehistoric tribe carrying an elder with them in their migrations via a travois - a huge expenditure of effort and resources. Why? The anthropologists posited: they were carrying their library. Their map (this was pre-GPS). Their wisdom. Their _memory_. Our culture dismisses anything more than a month old as worthless, practically. We leading-edge Boomers remember the stories our parents told of the Depression, and our own postponed retirements in 2008. But to what avail?

Thanks for the new word: Bezzle!

The youth today think we “old timers” know nothing because we’re relatively retarded regarding technology. I read that somewhere and that the more primitive the society, the more the esteem for the aged are because of their experience based wisdom.

Thank you Dr.Reich. Most easily understood explanation I’ve ever read.

Makes a lot of sense. Regulations=protections.

I know very little about finance, but I do know something about the history of the ‘29 crash and corporate Dem Clinton and the killing of Glass-Steagal. I do know that in NEw York State the crypto lobby has fought hard to repurpose old fossil fuel plants to “mine” cryptocurrency, and thereby exacerbate the climate crisis.

Thanks for reminding us of this, Joe. Indeed - perhaps the end to this ecological insanity will be a good thing that comes out of this crypto-crash.

When will we accept that we have the best democracy money can buy?

Got to eliminate speech = money! Buckley v. Valeo.

I have never been able to wrap my head around where crypto-value comes from. It set made of fairy dust. It may be plain as day to money people or math people (of which i am neither) , but i have always trusted the words of Warren Buffet, who allegedly said something to the effect of only investing in what you understand and trust. Whether he actually said that, I don't know, but it makes sense to me, one of, if not the smallest of the small investors cohort.

What an excellent column and short but powerful history of the ruin of Glass-Steagall and the decline of American banking and Wall Street itself through new finagles based on greed and the compulsive urge of so-called 'big investors' for vast sums of money and the political influence it can bring. Thank you for this, Professor!

I used to have a close friend who would continually promote Bitcoin to me despite the fact that I'm not a gambler and have for most of my life considered Wall Street to be a casino, more complex perhaps than betting on the nags and vastly more involved than playing the numbers (I grew up in NYC). I worked summers during school on Wall St and occasionally had fun playing penny stocks, but steered clear of the addiction that even penny stocks can lead to. I preferred to make income by actually working for it.

I demurred on Bitcoin because I felt it was apparent, without naming it correctly as you've done in this column, that it was just a Ponzi scheme. My former friend - who finally got to be too much for me as he moved into far-right-wing conspiracies, especially the anti-Semitic ones - had gotten into Bitcoin early and managed to make enough over the years to 'earn' enough to purchase a top-of-the-line Mercedes. More proof, he claimed, that crypto was the way to go if you're a "smart investor".

Such nonsense. While I do understand that crypto crazies collectively will lose vast sums of money as crypto collapses, I'd still like to see it gone and keep hoping for the end of speculation and dirty practices on Wall St. along with a return to rationality in banking and investments, or as much of it as has ever existed. Perhaps it will take another Great Depression to change the politics in this country to the point where there's consensus that reforms like Glass-Steagall, which worked so well for so long, are essential to the stability of the United States and our international financial system.

Thank you Professor Reich for illuminating this. I could never wrap my mind around crypto. It smelled like a Ponzi right off the bat. I'd be squirming right now if I was a crypto bro. As for the millions of regular hard working people that invested in crypto, reminds me of an old saying my dad used. "A fool and his money soon part ways."

"Investment must be rational; if you can't understand it, don't do it". -- Warren Buffett, 1991

This advice has kept me from several bad investments, such as Bitcoin, over the years. You should not depend on our government to protect you from making a bad investment, the government has become corrupt and incompetent. Even if Bitcoin is banned, there are plenty of other investment scams out there.

I remember reading Peter Lynch, who made a lot of money from real investing rather than today’s gambling, talking about the importance of understanding the company before investing in it. Good advice then, ignored now.

One of the reasons some people invested in crypto was distrust of our government. In particular how Wall Street Bankers, who were responsible for the 2008 debacle, were rewarded rather than penalized. Today, there less confidence in our government than there has ever been thanks to Murdoch’s “Misinformation Machine” of fake FOX “News,” the Wall Street “Urinal” and the NY “Joke.” A quarter of a century of half-truths, misinformation and outright lies. What can we do to take them down?

Believe the WSJ at your peril.

There is a lot to be said for the interest in crypto, why would so many flock to it? The use of Crypto is a tool, like other currency investments it is either backed by something concrete or vapors of air.

If it is a tool, then it is up to those with the Authority to make sure it is insured, or backed up, and salient as an investment or called out as fraud.

Those gaming the crypto systems are only able to do so as long as it is possible.

Just as mortgage companies were able to defraud so many consumers in 2007-2008 amd many lost their homes, because subprime loans were allowed On the Market, untested, unproven and who paid for the losses, the consumers. Banks and companies were Bailed Out to keep the broken system afloat.

Poor policy management leads to investment failures.

How can Crypto be made into something functional?

From a long time ago, I remember two things my finance professor (at Cornell's Johnson Graduate School of Management) said:

(1) The "bigger fool" theory of investing is when you buy something expecting that a bigger fool will pay you more than what you paid. This very accurately describes not only crypto currency but also a large part of the speculation in the stock market and real estate markets for the past decade or more.

(2) Attempting to fight inflation with monetary policy (interest rates and the money supply) is like trying to push on a string.

Of course we need to get this crypto bull crap put down and eliminated! It’s bad enough that we no longer use cash and mostly use credit cards! This is insane! There is a vast amount of thievery in the financial industry! I am distrustful bankers, stock brokers and lawyers! Not to mention many politicians. This money system is a house of cards. It always has been a ponzu scheme. It’s like an executive who makes 30 million in bonus after selling out the company and then refuses to give workers a decent wage. People who make the real money big bucks are thieves! Taking advantage of their position is like price gouging during shortages. The crypto thing is scary for the economy because it’s based on nothing and those who buy it are greedy. I hope they lose big time! Greed never pays off for society. That’s why it used to be a sin.

Don't throw the baby out with the bath water. To fight, get a lawyer.

Guess who exposes and prosecutes these cases? They have your back but need authority.

Some of my jurisdiction included whistleblower protection for employees of publicly traded companies. Should expand jurisdiction for the entire financial industry.

E.G. https://www.whistleblowers.gov/statutes/sox_amended

E.G. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/dodd-frank-credit-ratings-purge-wrapped-up-by-labor-department

E.G. https://www.sec.gov/enforce/how-investigations-work.html

I’ve been screwed worse by lawyers than any other profession! I expect them to be fair and moral and my experience was the opposite! I have a family member who is Yale trained lawyer and he is amazing both in is knowledge and his creativity not to mention his sense of morality!

It looks like it's time for regulation. the number of people involved in this bezzle that were in government is right in step with the rotating door of lobbyists. Even if I had money to gamble with I would not touch crypto. its very name is off putting. Makes me think of 'hypocrite'.

Very interesting!

I agree 100 % with your analysis and recommendations.

Mark Houshmand

Great work explaining the obvious, Prof. Reich. The requirements for any truly successful currency are: (1) acceptance by the population; (2) backed (in some way) by a trusted party; (3) a common definition as to how the currency is created and exchanged. The reality is that you cannot "mine" currency to acquire it, as it lives in the ether and no one stands behind it. If this sounds familiar, I refer you to the "tulip craze" in Holland, way back when.

I mostly agree but if you have minerals and even crops on your land, they may be used as currency. Under the Uniform Commercial Code, a note and mortgage (or any recordable loan document) can be the equivalent. "Negotiable paper." Derivatives are sold on stock markets as "investments". Even bad debts can be bought and sold.

Just a few years ago coal companies paid miners in scrip.

Some trade in futures of currencies that do not currently exist.

Conversely lots of people are "land rich" and are dirt poor.

"if you have minerals and even crops on your land, they may be used as currency." Is this accurate? Isn't it more true to say "may be used to secure currency"? Also, the coal companies, as did logging companies here in the west, used scrip to keep the worker dependent, since it could only be used in the company store or to pay the company rent for the company provided housing, etc. All this to try to understand your point in this comment.

Barter. Taxed as if currency. At one time many years ago I represented a lot of farmers and local taxing authorities. I'm sure that even today, people take ore, crops to be traded. Meanwhile check out the commodities market.

https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/irs-cautions-bartering-transactions-are-taxable-transactions#:~:text=Income%20Tax%20and%20Self%2DEmployment,receive%20a%20penny%20in%20cash.

Lots of businesses in the neighborhood took scrip... and are still selling it via the internet. Banks in the coal fields exchanged scrip. In this country some banks issued their own coinage and currency. "When the last bank notes came off the presses in 1935, over 14,000 banks had become members! All of them issued paper money with their own name on it, and all is still legal tender today."

https://robertreich.substack.com/p/what-the-crypto-crash-tells-us/comment/7171520?s=r#comment-7171520

I didn't get into it, Every contract is a "bargained for exchange." The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) is a comprehensive set of laws governing all commercial transactions in the United States. It is not a federal law, but a uniformly adopted state law. Uniformity of law is essential in this area for the interstate transaction of business. IMHO should govern every trade.

I also worked for SSA at one time. Some activity is "deemed" income. The issue is value. If something of value is exchanged...equivalent to currency.

I'm starting to get it a little; I was unaware that scrip could be used or traded outside the company community it was issued in. That's interesting. You once represented farmers and tax authorities, in what capacity and for what purpose, may I ask? Also, tralk about the consequences of taking the dollar off the gold standard, if you would?

Scrip? https://www.ebay.com/sch/i.html?_nkw=Scrip%20Coal&norover=1&mkevt=1&mkrid=711-156598-665184-3&mkcid=2&keyword=scrip%20coal&crlp=435075338776_&MT_ID=585556&geo_id=10232&rlsatarget=kwd-302856113745&adpos=&device=c&mktype=&loc=9011911&poi=&abcId=1141786&cmpgn=6537046517&sitelnk=&adgroupid=80161660722&network=g&matchtype=b&gclid=CjwKCAjwqauVBhBGEiwAXOepkQgJhKMk_53x4M7x5wVlKZ-R8K1xWfvsvdu5thKSdiCznBJWTxyDFRoC3vwQAvD_BwE

I was a lawyer. I represented several townships and other municipal entities in Pennsylvania. They had taxing authority. Most of the farmers were cash poor as I said before. Amish in two of the townships. They trade. Commodities for labor. Goods for services. Need to keep records. I included the IRS rules on barter. Don't want to pay taxes. They also consume a lot of their subsistence crops. Most farmers play the commodities market, get government subsidies, buy crop insurance. Most local authorities had wage taxes. The state of Pennsylvania had sales and use taxes. Traded commodities subject to tax.

I also was once the "bank" for the Federal Home Loan Board of Baltimore in my home county. Represented mostly farmers. Some places have ad valorem taxes based on " capitalization of net income" on rents and commercial property.

I remember when Nixon, without notice let the dollar float. Before that it was illegal to hoard gold. Gold speculation started immediately. Lots of fraud. I also remember when the Mexican peso went from 6 to a dollar to 60 to a dollar in one day.

Thankss for taking the time for this, it's appreciated. As a craftstman who has always been flummoxed by the arcane subtleties of the Market, you who understand them are like gods to me.

The Biden Administration and Congress should not only stop the crypto bezzle but, more importantly, take global monetary leadership in transforming the unjust, unsustainable, and therefore, unstable international monetary system. TTRIMS (The Tierra Transformed International Monetary System) framework is one way of doing this.

TTRIMS consists of a decarbonization-based international monetary system with its associated money-based financial system and inequality-reducing fiscal system. This transformed international monetary system is based on the decarbonization standard of a specific tonnage of CO2e per person, that is overseen by the UN People's Bank with its digital currency of the Tierra and its balance of payments system that accounts for both the financial and ecological (climate) debts and credits.

The Biden Administration can bring the nations together to participate in the 2023 UN Commission of Monetary Reform and Transformation and the 2024 Second UN Foundational Convention. This monetary leadership can be presented as a transformational Bretton Woods 3.0 that would incorporate the reformist Bretton Woods 2.0 of the IMF and its supporters.

I knew it was a boondoggle from the beginning and especially after the NY Times ran a special section explaining it earlier this year - and it still sounded like BS!!

I think it's a bit of serendipity that I just heard this article on BBC's "Business Daily" about an hour ago concerning crypto: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/w3ct311s

Looks like WSJ missed it. They should have spread the alarm 10 years ago.

I also read: https://fortune.com/2022/06/15/celsius-black-monday-contagion-liquidations-crypto-market-bankruptcy-restructuring/

Interesting but leaving one with little more than the ennui one started with. The entire concept seems like a way to dodge (hence dodgy) the whole concept of a cash based economy. When I try to mentally follow the Wall Street manipulations that led to the 2008 crash I find myself in the same kind of fog and confusion that Crypto lives in. I still remember the outrage generated when the Fed unshackled the dollar from Gold; "where is the vallue now!" people yelled. "The vallue has always been based on our trust!" came the answere. "How can I trust a dollar based on some "promise" made by someone I have never seen?" "....trust meeeee....." Anyway, Crypto apparently requires at least some kind of electronic device, a smart phone if out in the marketplace, and an app, all of which means good things for that market, no? Oh, the times they are a-changin' for sure.

Hell! I'm skeptical that the tech sector is ultimately, widely sustainable for the general population. Tech will be for the wealthy, who'll use it in getting wealthier! Think "Soylent Green," or even Vonnegut's "Player Piano" - which is more what I have in mind. See my link to a BBC "Business Daily" at the top of this sub-thread, which confirms my view - with regard to crypto, at least.

Good point, sustainablility. Coin of the realm has been thousands of years in creation, and suddenly here is this techno-reeliant archane "currency" meant to liberate the masses from the "tyranny of cash"?

>Exactly.< Of course, there's the carnage that will be wrought on the "all ya' got'ta do" mentalities that try getting into it halfcocked.

Thanks!

Hi Robert, crypto is the next step in social scalability thanks to the solution of the General Byzantines problem. While 99% of it is pure trash and speculation, it's the 1% that matters. Money has always been a social thing (see The Currency of Politics by Stefan Eich). Crypto is no different. Dismissing crypto as a ponzi is an oversimplification and means you don't really understand it.

what a cryptic take! Just what makes a system that is 1% ok a good thing? And if it's the next "step" I'm thinking "wild west" sounds a little too true, and only the predators and sharks like that scene.

Hi Michael, if it felt a bit cryptic it's because it was a comment and not an article. The internet in the 90'-00' was also called a ponzi and a bubble and if you were to invest 99% of it dissapeared but that 1% is what makes 20% of the SP500. Feel free to not invest and to be exceptical, it is a great thing indeed but when it has survived until today and the sharpest minds in the world are working on it, maybe there is something else than the ponzis that make the frontpages and even if you cannot properly value it or think it will fail, it should still be respected and studied.

Says a mark.

"Cryptically", per the other comment...

A 'Crypt" is where one hides things out of sight, Cryptocurrencies hide money from out of sight of the banking and taxing systems.

But, fools and their money are soon parted. I have little sympathy for those who lost money in Crypto. I've been waving off friends from it for at least a decade. But as profound as the crypto losses are to individuals, the greater danger has been to the stability of the financial system, even as it, too, cheats those in the middle class or with lower incomes. The value and exchange of money has been the most widely trusted element in human affairs, and as that trust breaks down, even the rich will feel it, as all financial values decrease.

I've been telling people this since day one....crypto currency was designed by criminals to hide money laundering in plain sight. It appeals to greed. There is no "saving" it....it's literally NOT worth anything. Get out if you can. This will be the next worldwide economic debacle. Don't be "that guy" the one who thinks you'll get bailed out. It's not happening.

It will happen in 2025. Not far from now…

Bill Clinton should not have signed the Graham Bliley Act destroying Glass-Steagall firewalls in the banking system. Under Glass -Steagall investors of paper assets and cryptocurrency would still be free to roll the dice but they would have to do it with their own money and take their own losses instead of being able to destabilize the whole banking system, because under Glass Steagall investment banking is a separate house that is not FDIC insured, so they can't pass their gambling losses onto the rest of us. Our money needs to be wagered against real fungible assets or it will be toilet paper! Note Bill Clinton was a Rhodes Scholar and Cecil Rhodes funded and set that program up to indoctrinate students who study abroad into British orientated financial thinking, and the Brits hold more whore house investments than anybody in the world. We need to hold more assets in the US Treasury backed up by physical economy investments which are under control of the US Constitution, and limit The Federal Reserve international parasite more. Lincoln and FDR issued T-bonds through the Treasury to build infrastructure which is a real fungible asset that improves the quality of life for ordinary people, but it also made the US a very wealthy powerful nation. As soon as a new generation forgets the brutal lesson of out of control wagering not backed up by enough assets of real physical value, and crypto currency is not backed up by real physical assets, the lobbyist are back. How in the Hell could we get Congressmen deeply invested in whore house investments to pass reinstitution of Glass -Steagall?

I'm old enough to remember when an ordinary person could keep money in a savings account or CD at the local bank, earn a modest amount of interest, and know that the money was protected by FDIC. Those days are long gone. My current bank (Chase) pays a whopping 0.01% interest on savings, yet the CEO is apparently worth millions per year!

I believe this started when larger banks started swallowing up smaller banks and gained control of the financial sector. Then came the repeal of Glass-Steagall and the watered down version known as Dodd-Frank. Now I can't even go into the local branch (a rare occurrence!) without being cornered by a "personal banker" who attempts to sell me investments. Thank goodness I already work with a financial planner who has my better interest at heart, or I would not have the security I currently enjoy.

You are right. My nose for scams smelled the stink long ago.

I unfortunately my son that "helps me", took all of of my bank savings and bought into "some" crypt system. I didn't know until I saw no money in my savings at the bank and he said that moving over to crypt would pay me more. I love my son but he has cost me BIG 3 times.

It is hard for me to believe that anyone--anyone--would fall for the idea of "cryptocurrency." But then, I never would have believed there are enough gullible people in America to turn Donald Trump from a con artist into a president. What a country!

My wife, in particular, has strongly wanted Glass-Steagall put back in in strong form for several years. I agree commercial and investment banking need to be clearly separated.

Crypto, from its very name, has always sounded to me like a service for criminal activity and for people who are trying to hide their income from the IRS. My response to people who would tell me that they were going to make huge amounts of money by buying Bitcoin or , later, other crypto currency’s, was, “You’re nuts! It’s a scam, and it’s supporting cartels and money launderers!” My assumption was that people who got in and, as soon as I their money doubled, take out their principal, would only lose their original investment and break even, except for the taxes they paid on their gains. But, just like the banking/Wall Street/housing scams, every one just kept thinking that this train would never stop.

I hope that this time the perpetrators will go to jail, even the “smartest man in the world “, Elon Musk.

Eric West

I think that a semester of "home economics" should be required in high school curriculum. Media is saturated with advertising access to easy money and credit.

Children need to learn how to budget and plan their path to economic stability. My parents grew up poor during the Great Depression, so I was constantly reminded to buy only needs, not wants; save first and pay cash; and build up a rainy day fund because the rains will surely come.

Government regulation is needed, but education would reduce the number of victims.

I like to think of Crypto an "investible", just something that is not money but can be exchanged for money, has little practical use, but is expected to hold its value, more or less. Crypto is in the same class as rare art, precious jewelry, antique cars, gems . . . and tulips. When inequality is great, as it is now, there is a lot of excess money seeking "investibles" and somebody created crypto to satisfy that demand.

As so eloquently explicated by Professor Yural Noah Harari in his book Sapiens, cash money is but a means of exchange rooted in faith - i.e., universal trust in the value of a dollar. In contrast to the inefficiencies of a barter system, trust in the value of money facilitated the explosive growth in the world economy by enabling producers to more efficiently trade the value of their products. In contrast to crypto, trust in the value of money has to be earned by institutions that are held accountable. While our traditional global financial system is quite imperfect due to lax regulation, there is zero accountability in crypto. It’s nothing but a bag of gas generated by computer algorithms.

For certain crypto needs visibility. A means to know who puts the money in, who gets it and where does it go. Even without this current crash experience crypto has opened up a electronic offshore movement of money. To my understanding laundering, tax evasion, and other potentially financial damaging actions take place there. Yes it is time to regulate. As far as the crypto companies are concerned my attitude is No bail out.

From what I understand, crypto currency uses huge amounts of electricity. I think that’s a real problem. Maybe I am wrong.

You have made it loud and clear that the executive administration's since Clinton have removed the safeguards for the unsophisticated investors afforded by the Glass-Seagal Act.

The Obama administration and Congress allowed the continued rape of We the People by making whole corporations and allowing these very institutions to plunder the real assets of the American citizen through foreclosure and decreased Bankruptcy Act protection

The coup de grace is the lobbying efforts on behalf of these bezzlers by those executive treasury administrators, who have held these positions in DEMOCRATIC PRESIDENCIES (CLINTON and OBAMA) .

You want us trust the Biden administration!!! I trust your sincerety and I respect your candor.

You have actually made a good case that We the People have been defrauded by these individuals and both political parties. Justice should demand that all collusion be opened to air and that We the People receive reparations for the damages. I do believe that our Forefathers including Hamilton would agree.

i as a rule i do not invest in things that i dont understand so i am immune to the whole cryto scheme what scares me is after 2008 crash there has not been a bit of regulation to prevent this from happening again

Ponzi Scheme. Like you, I have seen many variations of this scheme over the years and Bitcoin is a scheme without any solid backing. We need Glass-Stegall Act back in to Law ASAP to stop the financial gambling.

How lucky you were to have Galbraith as a mentor. You do him credit!

Not sure I have a bitcoin worth of sympathy for those who are losing their digital shirts. This isn't subprime mortgages where a known financial instrument came with a house as an equity building asset. This was pure smoke and mirrors.

Bezzle, glitter and fairy dust. A grift. A solution in search of a problem - and not really a solution at all. When do people start to learn that they are suckers and that we need to have standards, laws and intelligent and trained people to enforce these laws and standards to keep us individually and collectively secure? Moreover, an economy that provides strong middle class incomes and does not generate extremes of wealth and poverty is less prone to people trying to get rich quick or to be smarter than everyone else through means that are not really that smart at all. Another signal of the American fall, happening in real time before us as we simply seem uncapable of mustering and applying the collective insight and fortitude to identify and address real problems instead of farcical conspiracies and unwarranted fears. The 2022 midterms appear poised to be another step into the abyss.

It's own name, crypto/hidden, reveals everything...

The use of “alternative medicine” is symptomatic of the failures of conventional medicine. It offers hope past the edge of the established system’s limits, and once in a while it even works (and gets absorbed into the establishment).

Likewise, crypto is not fundamentally different from conventional capitalism, and offers hope beyond the edge of what is currently conventional. Capitalism is just the name of the most successful Ponzi scheme. It too creates tremendous wealth where there is little to no value. In capitalism, we compute the value of the bits going in, including the labor and even some reckoning of the creative innovation, and then charge more than that value. We call it profit, as if that makes it not-ponzi.

My point is that condemning crypto as fundamentally illegitimate is only valid if the same condemnation is applied to its wealthy cousin, capitalism. It follows then that like capitalism, or abortion, or alcohol, or guns, you can’t stop it, you can only make it as dangerous as possible, or regulate it. Those are the only two choices.

More precisely, profit derives from paying workers less than the value of their production.

Right, and the Ponzi part is legitimizing profit to the corporate owners when it is not a product of delivered value. One could argue that the market has told us that people value having it now and at the asking price -- that's value. Fine, but that is exactly the same for crypto, and pet rocks, and the prevailing argument seems to be that this is the problem.

Deep thought. Can we dare to question capitalism? Will we ever get back to serious regulation?

We damn well better restore robust regulation. Capitalism is ONLY an economic system. Humans have other than economic needs. Therefore, capitalism must be regulated so as not to trample everything in its path, including the actual humans. This is nothing radical. Capital has been regulated for as long as it has existed, whether by personal brute force, or the local king, or the distant emperor, or the elected government. The question is only whether we will regulate it as we do now, for the oligarchs, or for the benefit of people in general and society as a worthy entity.

Cryptocurrency has always struck me as the Tulipmania of our time. It has no underlying value--none--unlike real currency, issued and backed by sovereign governments, whose value lies in the economy that supports it.

I agree with you. Minerals, crops, or anything of value (agreed on by the traders) can be used as currency. Usually, though, those are not standardized currencies. If the currency is of no intrinsic value (e. g., paper), it must be backed by a "trusted" institution. As far as the coal miners a few years ago, they really did not have any choice whether to accept payment in scrip or not. As far as people that are "land rich but dirt poor", one is not truly rich until one exchanges assets for a liquid, generally accepted currency. Everything else is just bartering.

The utility promise was p2p cash. Unfortunately 99% of the market forgot that or deliberately ignored it to built the biggest casino of our generation.

But that doesn't mean that the promise of being master of your own wealth, making transactions instantly around the whole world to anybody for pennies without trust in a third party isn't a great invention or even a revolution. Look at the coins that are making that happen: BitcoinCash, Monero, Dash.

Yes, there are thousands of crypto schemes out there but there are legit companies with legit new technology that can take the power away from the few and embolden the masses through a democratic process. Look up Charles Hoskinson founder of Cardano and look up World Mobile and what those 2 companies are doing in Africa. We will be eventually voting on a decentralized blockchain. Crypto isn't a get rich quick scheme, it is a get rich faster than busting your ass for decades tho, working harder longer hasn't paid off for me, learning to trade crypto has.

Crime. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidblack/2022/03/11/cryptocurrency-fuels-explosive-growth-of-crime/?sh=37a726c5618a

Yes, exactly - which should be of great concern if our government has made progress on sanctions technology, international banking standards (e.g. no Swiss anonymity), & happens to be facing challenges regarding election security (as was the case with Facebook/Cambridge Analytica & circumvention of FEC rules); basically, the price being paid to facilitate electricity price arbitrage & speculation is far too great!

With that juggernaut of smooth-talking lobbyists at their doors, who will be able to educate the hugely octogenarian Senate about crypto, much less how to regulate it to protect people who invest life savings into such a scheme? I don't hold out hope that Congress will act effectively on this one.

Republicans only have one constituency -- except Grassley on this issue -- and that is contributions. Vote them out (including Grassley).

How did so many smart Americans get pull into this ??? Does this mean they aren't really smart ???

✊🏼

With such misleading journalism (because it's always more popular to defend statu quo and reinforce baseless stigma) no wonder the general public remains misinformed

-Celsius had 1.7M customers

-Celsius was CeFi, the opposite of DeFi (!)

-TerraUSD is not a thing. It was Terra Luna and UST. It was not even remotely close to being a bank.

- If crypto is Ponzi, then so are pension funds (new money pays old investors) gold (need a greater fool to sell it to) and fiat (a debt-based pyramid scheme) so let's not go there.

- DeFi/crypto is indeed a baby still and the wild west, but contrary to your claim, all transactions are on the blockchain, so it's a much more transparent sector than traditional finance and banking.

-Crypto lobbys IN FAVOUR of regulation, not against it! The only way to reach mass adoption is to have clear regulations so that everyone is on the same level. Show me one single proof that "whose kingkins want the Ponzi scheme to continue". Extremely unprofessional to make such assumptions up

- You wield the word "Ponzi" for dramatic effect but seems to ignore its meaning. What is the difference between adoption and Ponzi? By your implied definition, there is none.

Bitcoin is digital property. Crypto is starting to show some solid product market fit solutions, and each bear market cleanses the industry of bad actors.

According to the media, this is the 8th time that crypto died.... And like any market cycle, after a bear there is a bull.

An article like this one is a bottom signal; bulls may be back as soon as Q1, 2023!

Human institutions like humans need regulation. Take for example the Supreme Court.. For me no transparency means no deal.

I agree absolutely. I have always thought crypto stank like last week's fish. I can't believe there is a an ad on TV, trying to get people to put their retirement funds into crypto. SMH

You have hit the nail right on the head. Prior to the establishment of the new financial order and regulations leading to the institutionalization of the World Bank and IMF, (1920's) J. M. Keynes Papers pave the way, with sufficient intellectual critiques, resulted in appropriate policies and laws to guide the regulation procedures of the market.

Ever since, the cryptocurrency products emerged, where is a solid evidence of a grounded paper guiding its existence and regulation procedures, which are accepted in mainstream academics?

All the promoted papers are ideological and propaganda; having within it a lobbying strategy of attaining brand credence by associating with the big corporate firms under shadow deals.

How do we then expect such an illogical and emotional driven system of investment to survive in time of adversity?

The parallels between bitcoin and the gold standard are not complete without the government using it but there are unnerving parallels nevertheless.

The parallels to oligarchs resistance to messing with their financial maneuvering are also worth remembering. Coup plots are not unprecedented

https://timeline.com/business-plot-overthrow-fdr-9a59a012c32a

Perhaps worth an RR essay?

I did consider investing in crypto currency, but dared not jump in until it looked stable and reliable. I am so glad that I did not invest even a nickel in this! I truly feel sorry for those who took a bath. What we need is a system that not only regulates financial markets, but prevents the rich and powerful from escaping with golden parachutes.

I have felt from the beginning that all this crypto business was questionable. Thank you, Robert, for telling us why.

This kind of event makes me so angry. The government should never have let the safe guards be removed. "If it sounds to good to be true," and "You can make a fast buck," have always been warning phrases.

Have been suspicious of crypto from the beginning. Never been tempted to put a penny into it. Now, reading your report, I see that my gut instinct was “right on the money” and hope that either the whole thing becomes extinct or else submits to appropriate federal regulation. When will the lobbyists stop running the show?

I knew Crypto was pure, unadulterated BS as soon at it hit the scene. "Fiat Currency" is backed by the full faith and credit of whatever government issues. Crypto is backed by the full faith and credit of Fred in his mother's basement, Henry in the C-Suite, and banks of carbon spewing sever farms in Russia (but not China anymore because they're smarter than we are).

Exactly

Scary! I'm glad I've had nothing to do with cryptocurrency. I know virtually nothing about it, & I don't really want to know. I just hope that cash remains a viable way to pay for things.

Those who invested in Crypto currencies will blame President Biden for the crash. Every time I tried to argue against the Ponzi scheme, I would get a rash of how Biden was ruining the dollar or how I don't know anything about chain whatever. What I do not like is the Mining for crypto curacies that use up so much of our hydroelectric power in the huge servers they use to mine it near the Columbia River where electricity is cheaper than most areas leaving only more expensive electrical power for the rest of us.

The coinage imagery is fierce, formal and horrid, much like those pushing it. I much prefer to heft my old silver 'Peace' dollar (1923), worth 100 cents once, and behold its gorgeous imagery. Appearances do matter ..

There’s no sense how this government is not acting to avoid this vacuum that is destroying the once (1950s) great economy , I am just afraid that the1% will control all the puppets and we will be in hunger games or ponzi scheme

You wrote an article in The NY Times about Big Tech being too centralized and controlling 99% of the internet. Now, you find all decentralized web crypto projects Ponzi schemes.

Where are the black tulips when we need them for security?

Respectfully, to say all cryptocurrencies are a Ponzi scheme sounds incredibly ignorant. Decentralization was born after the 2008 when our government had to bail out the banks frothing with greed. There’s no transparency in our traditional markets, yet all transactions in blockchain are available to all to see. Yes, the bad actors in crypto are getting washed out - deservingly so. But there are projects like Cardano and hundreds of metaverse projects giving economic power back to the people. The global adoption of blockchain technology is now termed Web3 giving people the ability to protect their privacy. Your generalization that all crypto is a Ponzi scheme shows you have not researched the entire sector questioning your credibility.

Thank you. The first time I have read anything substantive about crypto. I think that, somewhere in the civilized world, are legal systems that have done similar investigations into the reasons why the crypto ponzi schemes are allowed to move large amounts of money. I hope the now and near future crypto crashes bring on many investigations.

You said it right in the middle, Robert:

Crypt-evangelists want the new Ponzi.

The US hunger for new trends, for decades now a developed global phenomenon, makes the complacent easy targets as ever.

"But even though money is plentiful, there are always many people who need more."

The Atlantic made a great article about the Why a few years ago.

https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2018/12/rich-people-happy-money/577231/

Short answer: At a certain level, welath just becomes reputation and a contest who has the greatest... ... I think you get it.

Pass a law saying people should no longer crave more money. Brain surgery gratis.

Yes, marks get taken and in some cases they lose everything. It is so easy to climb in crypto as it is going uphill and those that do fail to see any risk. Investments are expected to go up but in many cases they go down. I have pity for those who put all pigs in one pot but another part of me says: "What did you expect?" Sure we need regulations to protect these fools because they can drag the rest of us down with them. It all comes down to having effective laws and we simply do not want laws to protect us from those who would bezzle...at least the GOP does not want those laws.

I constantly wonder why 10-20% of people are so stupid and 10-20% will do ANYTHING to cheat the rest.

Yes, Chuck Campbell, I agree - "Stupid should be painful. Stupid and greedy should be debilitating." And yet, the greed lesson never seems to take. Could it be because the "successful greedy" never suffer any consequences?

With the internet, there is a sucker born every second. Who would ever invest in a scheme pushed by Antony Scaramucci? His recommendations are below. These guys always double down no matter how wrong they are.

"The selloff in bitcoin and ethereum are buying opportunities," Anthony Scaramucci said on Monday.

He still sees bitcoin going up to $100,000 over the next 12-24 months.

"An improving macroeconomic picture will be a factor in helping crypto prices recover," he said.

The frustrations of the commentators coming thru on this venue seem to us in this quarter can be summarized as follows:

1). For the moment at least, we lack the power to adequately influence the voting in our favor;

2) We cannot shame the gridlockers for there is no shame in their game; and

3). Examples of "Profiles in Courage" are too few and too far between. Of course, there are many, just not enough.

Puts a feller in the mind of the French Revolution caused by the Monarchy and the Church having

"All" the money while "The Poor People of Paris" were left to have bread riots in the streets of Paris. And, to top it all off, there was no avenue for the people to effect change in the operation of government.

The good news here now: I'm pleased with the way the 1/6 Committee Hearings are going and the prospects that might result therefrom, prospects that all of us here want to see happen. If only we could get more Democrats elected and hold their feet to the fire to pass Campaign Finance Laws so strongly written that the Extreme Court would not dare strike them down. McCain-Feingold anyone? Remember, and we need to remind the Nine Robes, that it is not their job to legislate; that is the job of the Congress. Period. Full stop.

David Gelles is coming, or has arrived, with a book THE MAN WHO BROKE CAPITALISM in which he claims, in an interview, to present the rise of Neoliberal Capitalism and the harm it has done and how CEO capitalists themselves are beginning to see the need to reverse course. The MAN, the breaker, was Jack Welsh of General Electric. Gelles was interviewed by Walter Issacson on Amanpour and Company CO. this week. Walter does his homework and it shows in his work. Gelles discusses Stakeholder-Shareholder concepts. Some mfg is coming back to our shores and they are in high tech with GOOD paying jobs. Moreover, the virus has shown us the folly of losing control of the supply chains of crucial products made off shore. My contact in the Columbus, Ohio metro area tells us that Intel (I think) is opening an operation there that will employ a very large number of workers and the jobs will start at $100,000 a year.

So, "Hang on Sloopy". Change is a commin' -- good change.

" ... criminals have been using cryptocurrencies to conceal the enormous amounts of money they are receiving for their crimes, specifically money laundering, drug trafficking (illicit drug sales), and terrorism financing. It was found that offenders can conduct business, launder money, and make a profit by using cryptocurrencies to facilitate their crimes, creating for crime opportunities permitted by cryptocurrencies. These opportunities include the ease of floating from one crime to another and using cryptocurrencies to cover offenders’ tracks, where cryptocurrencies can transact, launder, and conceal all in one. It was found that offenders gravitate towards using bitcoin to facilitate their operations, most likely due to its popularity and reliability. When looking at the crime of money laundering and illicit drug sales specifically, it was found that offenders can generate higher operation amounts, spanning into billions of dollars, all while evading detection. With the assumption that transnational criminals are rational beings, money laundering using cryptocurrencies has enormous benefits with these high operation amounts. This coupled with the low chances of being caught by law enforcement, makes money laundering a feasible crime where the benefits far outweigh the risks...."https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_etds/70/

Campaign reform? Ultimately, until corporate interests are disentangle from selection of governmental “public servants,” this, as well as all of the rest of the bad behavior will continue. How to incentivize good behavior becomes the salient question.

I am in full agreement with your commentary. Regulation is essential.

I am in favor of bringing back the Glass Steagall Act. From 1933-1999 there was no problem. Dodd Frank was better than nothing but Glass Steagall was much better yet.

I agree Crypto currencies have no real use in Finance.

I do not want the banks to operate like las vegas. I do not want another 1929 or 2008 crashes. I wish the dems in congress would do more and talk to the voters more to keep the voters safer. 'Eighty nine years ago today the Banking Act of 1933 — also known as the Glass-Steagall Act — was signed into law by Franklin D. Roosevelt. It separated commercial banking from investment banking — Main Street from Wall Street — in order to protect people who entrusted their savings to commercial banks from having their money gambled away. Glass-Steagall’s larger purpose was to put an end to the giant Ponzi scheme that had overtaken the American economy in the 1920s and led to the Great Crash of 1929.'

I have never understood cryptocurrency and for that reason I would never invest in it. I’m a bit of a simpleton with respect to investments perhaps because my dad worked at a bank and my parents lived through the Great Depression.

But I do understand oversight and regulation in any field because only with oversight are humans able to overcome greed. I don’t think most humans, unless they are rooted in a form of self awareness, see greed, or see it as something to avoid, or see it in themselves. It’s in all of us, and as a chant in aJapanese Buddhist tradition goes, “greed, hatred and ignorance rise endlessly…”. The last part of the chant is, I vow to abandon them.”

The American culture seems sometimes based on greed, whether it’s about money or power. Regulation creates stability in my opinion. But then… I’m not an economist,

I have never understood cryptocurrency and for that reason I would never invest in it. I’m a bit of a simpleton with respect to investments perhaps because my dad worked at a bank and my parents lived through the Great Depression.

But I do understand oversight and regulation in any field because only with oversight are humans able to overcome greed. I don’t think most humans, unless they are rooted in a form of self awareness, see greed, or see it as something to avoid, or see it in themselves. It’s in all of us, and as a chant in aJapanese Buddhist tradition goes, “greed, hatred and ignorance rise endlessly…”. The last part of the chant is, I vow to abandon them.”

The American culture seems sometimes based on greed, whether it’s about money or power. Regulation creates stability in my opinion. But then… I’m not an economist,

Bezzle! What a great word - and I never knew it existed! It conveys the shimmer of the disappearing edge of things, where reality meets unreality. Word of the Week!

I think Senator Elizabeth Warren (along with Robert Reich) have been the ONLY lonely wolves crying in the wilderness (the "shit show that Congress is") that regulators should do something before the cypto bezzle meltdown caused the little fish to lose everything. Has our Republic become so corrupt (with lobbyists and money flowing into politicians' pockets from every special interest group/corporation) that we are in danger of falling like the Roman Empire did so many centuries ago? Certainly, the failure of Congress and the SEC to heed the warnings of these lone wolves are IMHO mostly due to corrupting influence of money in our political sphere.

I once had an hour-long meeting with the Wall Street trader involved with development of the “lightning trade” system. At one point he stated that “Wall Street thrives only by raping the masses” (his word, not mine).

How long will our “leaders” and regulators continue to condone such rape (not to mention “pillage” and “plunder”)?

How can crypto possibly survive without regulation? Wealthy scammers will just manipulate values by using the "pump and dump" method, whereby they buy low, bump the value up and then quickly sell at the higher value. The $300 billion loss of crypto value that we have seen in recent weeks is a huge transfer of wealth from the small investor to the wealthy.

Really less a transfer & more a destruction, yes? (The trades aren't zero-sum: when the capitalization of the market drops from $3T to $1T it is the money invested that disappears from the economy & which cannot be used for some other salient purpose.)

It seems to me that the the "value" of crypto doesn't just disappear- doesn't it have to be taken out of the block chain and transferred somewhere else in order for the crypto to lose value?

A simple example: suppose a ticket to see your favorite band can increase in value well beyond its face value (in anticipation of the event), fall well below face value (after the arena gates close), and may even change after that (if the ticket proves to be memorabilia)... but isn't worth anything if the band breaks up, the venue is closed, or even if resale at a profit is legislatively prohibited. Further, imagine all tickets for a given have sold.

If the (second-hand/quoted) ticket price falls during the anticipatory period, the value of all outstanding tickets decreases - and, unless the price of tickets increases again, that "value" (really, wealth) is lost: anyone who paid more is now stuck with a loss - with the $ they invested in the ticket no longer available for other salient purposes (Bill Graham continues on his way - as he can create new tickets or trade them at will - though he is likely not a buyer!).

Only so much Bitcoin can be mined (there is a hard limit to the amount that can be created - which is not true of most other cryptocurrencies)... so scarcity *could* prove to cause a valuation above what it's marginal cost of creation (i.e. the cost of mining an incremental unit) happens to be. However, keep in mind that a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin is a dematerialized asset, i.e. one unit of cryptocurrency has no value as a physical claim to anything (it is not a gold-backed dollar, right to a cash flow of a corporation, repayment obligation, etc.); as such, if it is not a store of value, medium of exchange, and method of account it may not prove to be of value to a financial system regardless of scarcity - as its appeal for cross-border finance would be consequently minimal, if extant at all.

Thank you for your comments, Mr. Chopra. You have a much better understanding of crypto than I do. What puzzles me, though, is how the value increases and decreases. In your example of the ticket for my favorite band( Tuba Skinny), doesn't the value go up because there is demand for tickets (people are buying)? Likewise, doesn't the value of crypto go up when there is demand, and value goes down when there is a selloff? I don't understand how value just magically disappears.

Value could be like beauty, i.e. in the eye of the beholder: absent any metric other than the cost of creating it, the price is simply what the market will bear; given volatile swings in price and an extreme range in short periods of time (e.g. $6k to $60k in one year & back to $20k in one more), speculators likely play a role as they come and go (e.g. as they are called away from Tuba Skinny for Madi Gras in our example - akin to a margin call from a broader market that has also corrected 30%)...

OK, wise guy, and I mean that complimentarily. You are a national treasure so how's about we spend you? I need your attention. I keep asking you to call an ad hoc wisdom council. You go first. Pick someone great. Then the two of you pick the third, etc. Get a bunch of the most intelligent and well-respected people, who confer on what they would do if they ran the country, and everyone would listen. We are gadflies. We don't have a voice. This would create one.

I guess it depends on what we collectively believe the role of government should be.

If we believe it should leave us be totally free, including the freedom to invest money however we want, with possibly devastating consequences, and let learning those consequences the hard way be the way to educate and act as a feedback system to self correct.

Or should government be to protect us against possibly risky and dangerous ways to invest ones money and safeguard the entire financial system.

Difficult choice. I think I would want government to require full transparency from the investment platform, and save guard the whole financial system from these potential destabilizing sub-systems, like the separation between banks and investment firms used to do.

Absolutely spot on, as Krugman and I have argued. There's a lot of techno-babble in the crypto discussion.

--J. T. Taylor, Ph.D. in Economics, faculty at Temple U., retired.

This is so far from my areas of expertise but I've had my suspicions for a long time. Seems you have been proven correct....and are wise. Thank you Professor for educating me once again. Please now educate the Fed and any others who need to know.

I've never had enough money to be able to invest in anything, but if I did I would never gamble with more than I could afford to lose. I don't buy lottery tickets or go to casinos either. I don't even understand what crypto money is made from. What are crypto mines? I could look into it and try to understand what it is, but I'm not sure I'm interested. It sounds like ethereal ghost money to me. But then, what is a dollar beyond the paper it's printed on? I understood the gold standard but when we abandoned that it stopped making sense. Economics is all a ponzi scheme to me. Who has actual money? Most countries are trillions of dollars in debt. Yet they all keep spending. It's a mystery to me.

In the NYT today Maria Bustillos wrote, "...crypto is just one aspect of the larger blockchain universe. Its skeptics and fans alike must learn to see it as a technological experiment, instead of just a blatant scam or a speculative path to riches." I would love to know your take on that. Is there in fact something larger about this that we're missing?

I was sickened to read that the crypto industry's intensive lobbying has put in its back pocket scores of former government officials and regulators - including a number of very high-level ones. They’ve been bought off to protect an industry that the current SEC chair describes as "rife with fraud, scams, and abuse." What nice people.