Has Joe Manchin really, finally seen the light? Word is that President (sorry) Senator Manchin has agreed to roughly $433 billion in new spending, much of it focused on lowering energy costs, increasing clean energy production, and reducing carbon emissions.

Part of the Manchin-approved deal would raise $739 billion in taxes over the next decade — including a new minimum tax on corporations and additional funding to help the Internal Revenue Service pursue tax cheats.

1. A few grounds for skepticism

If this deal happens, great. But by my count this is the third time Manchin has agreed to support something Democrats desperately want, only to reverse himself a bit later.

There’s also the inconvenient reality of the ever-elusive, often bizarre Arizona Democrat Kyrsten Sinema, who has made opposition to tax increases on the wealthy one of the cornerstones of her short, regressive time in the Senate. (Remember, Dems need 50 votes.)

Putting all the blame on Manchin and Sinema for stopping Dems from raising taxes on big corporations and the wealthy lets too many other Democratic lawmakers off the hook.

Democratic senators and representatives from New York, New Jersey, and California have insisted that any tax bill must raise or eliminate the $10,000 cap on the state and local tax deduction, which has hit higher-income taxpayers in these states. (It was the only slightly progressive feature of the Trump tax cut, thrown in to penalize these anti-Trump jurisdictions.) Will they go along with the Manchin-supported tax increase?

Many Democratic lawmakers cried foul recently when Democrats on the House Ways and Means Committee considered imposing Social Security payroll taxes on wages and self-employment earnings above $400,000, to help fortify Social Security. Will they go along with the Manchin tax increase?

Meanwhile, Democrats such as Senator Jon Tester of Montana blocked Biden’s plan to tax unrealized capital gains at death, expressing concerns about what it would mean for family-owned farms and businesses. Translated: They’ve been bought by Big Ag. Will Big Ag go along with the Manchin tax increase?

House Democrats shot down a plan to require banks to report annual account flows to the Internal Revenue Service, saying it was too intrusive. Why should Democrats object to giving the IRS the data it needs to collect taxes that are due? Will they go along with the Manchin tax increase, some of whose revenue will beef up IRS enforcement?

The record isn’t encouraging. Democrats have so far failed to increase taxes on big corporations or the wealthy, even though a Democratic president now occupies the White House and Democrats control both houses of Congress.

2. The Manchin-approved tax is still small potatoes

Even if the Manchin-approved $739 billion tax increase over ten years gets enacted, it would still be small potatoes considering that large corporations have been enjoying record profits (even with the current economic turmoil, they’re sufficiently flush to be buying back their own stock at near-record levels); that the ratio between the pay of CEOs in large corporations and the pay of average workers has never been as large as it is today; and that the richest Americans have by now accumulated the largest share of the nation’s wealth since the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth century.

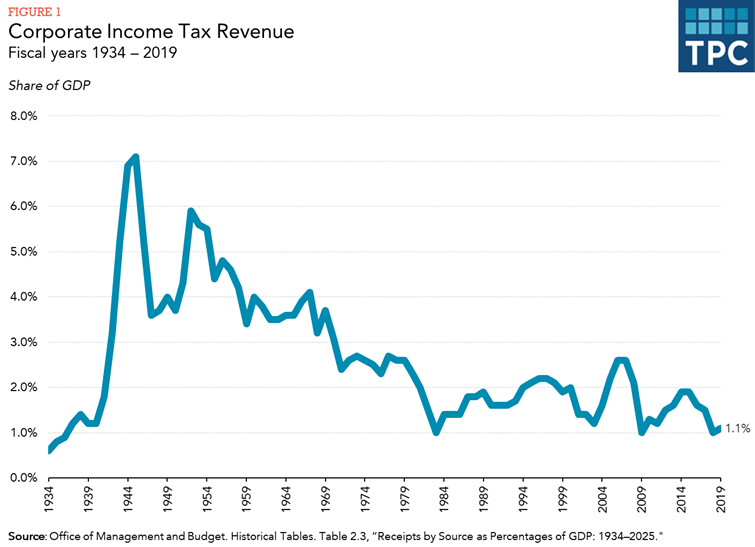

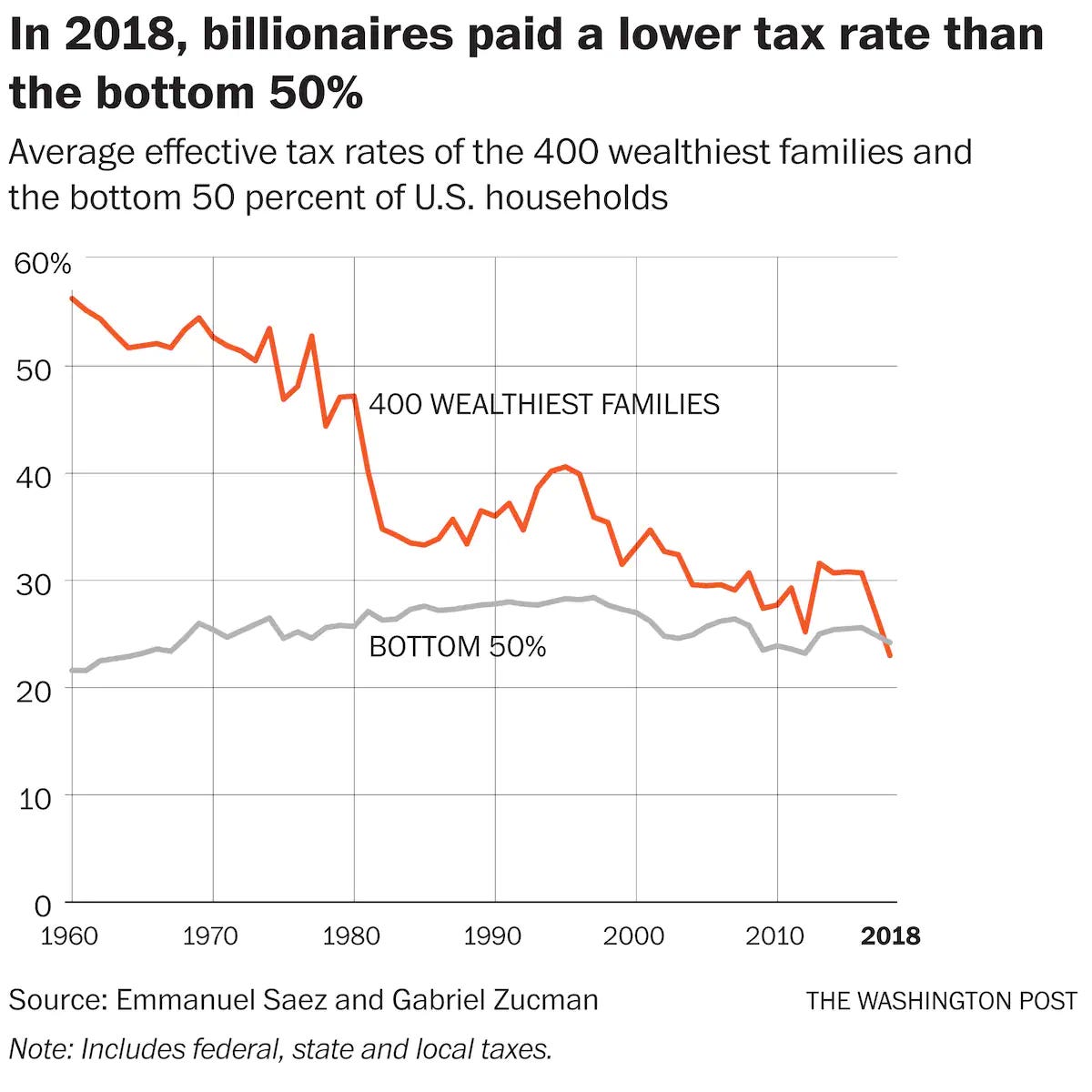

And it’s small potatoes considering that tax revenue collected from corporations is at a record low as a share of the economy, and that the super-rich are paying a lower effective tax rate than the average tax rate paid by workers in the bottom half of the income distribution.

3. What’s behind the Democrat’s failure to raise taxes so far?

Part of the Democrat’s problem is that the party has become such a big tent that it’s no longer a tent at all. It’s more like a leaky tarp — and what’s been leaking in is big money. As I’ve noted here, the Democratic base has steadily shifted to include more high-income suburban voters while drifting away from its working class roots. So when it comes to raising taxes on the rich, Democrats increasingly find themselves facing their own most active constituents.

Another part of the Democrat’s dilemma is their dependence on big corporations and the wealthy to fund their political campaigns. Many big American corporations are equal-opportunity bribers whose executives and PACs give generously to both parties. Meanwhile, rich liberals who fund Democrats tend to be almost as unwilling to part with their money as the rich conservatives who fund Republicans. The result is a reluctance among legislators, Democrats almost as much as Republicans, to bite the hands that feed them.

There is also the inconvenient fact that nearly half of retiring Democratic lawmakers are ending up as lobbyists for big corporations and the wealthy, as are Republican lawmakers. (It’s not that they’re greedier than former generations of retired lawmakers; it’s that lobbying has become far more lucrative.) And what do Washington lobbyists do? A significant part of their time and energy is focused on preventing tax increases on big corporations and the rich, and seeking tax cuts and loopholes for them.

4. Where does all this leave us?

When more of the nation’s wealth and income have moved to the top than at any time in the last century, and when taxes on the top are at their lowest in more than fifty years, the least we should expect from Democrats is to raise taxes on the wealthy and on big corporations. Such taxes not only help the nation pay for what it needs (including measures that slow climate change). They also reduce record levels of inequality.

If the latest Manchin deal becomes law, two cheers for the Democrats. Even though it’s not up to the scale of the challenge, it will give Democrats something to crow about in the upcoming midterms.

If the deal falls through, shame on them.

The difficulties Democrats have had so far in raising taxes illustrate the vicious cycle at the heart of American capitalism today: Because wealth and power are inseparable, as more of the nation’s wealth concentrates in a few hands, the greater the power those hands have to reduce taxes on themselves and to shift taxes onto those with less wealth and power. The bottom 80 percent of Americans (by income) is now paying a larger share of the nation’s total tax bill (including Social Security taxes, sales taxes, user fees, tolls, and property taxes) than ever before, yet arguably getting less return on their tax dollars. Meanwhile, their incomes have stagnated or declined, adjusted for inflation, and they have little or no savings.

Let’s hope that Joe Manchin’s change of heart results in legislation. But let’s not forget the twin challenges of growing inequality and big money drowning American politics. They are two sides of the same crisis of American capitalist democracy. More than at any time since the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth century, America needs a pro-democracy movement focused on getting big money out of politics and reducing near-record inequalities of wealth and income. One cannot be achieved without achieving the other.

Share this post