Today marks the start of the school year for many public schools. Which makes me think of Alice Camp. (I wrote about her some months ago. Many of you have asked me to repost what I wrote — and add a bit more about her and about our teachers. So here goes.)

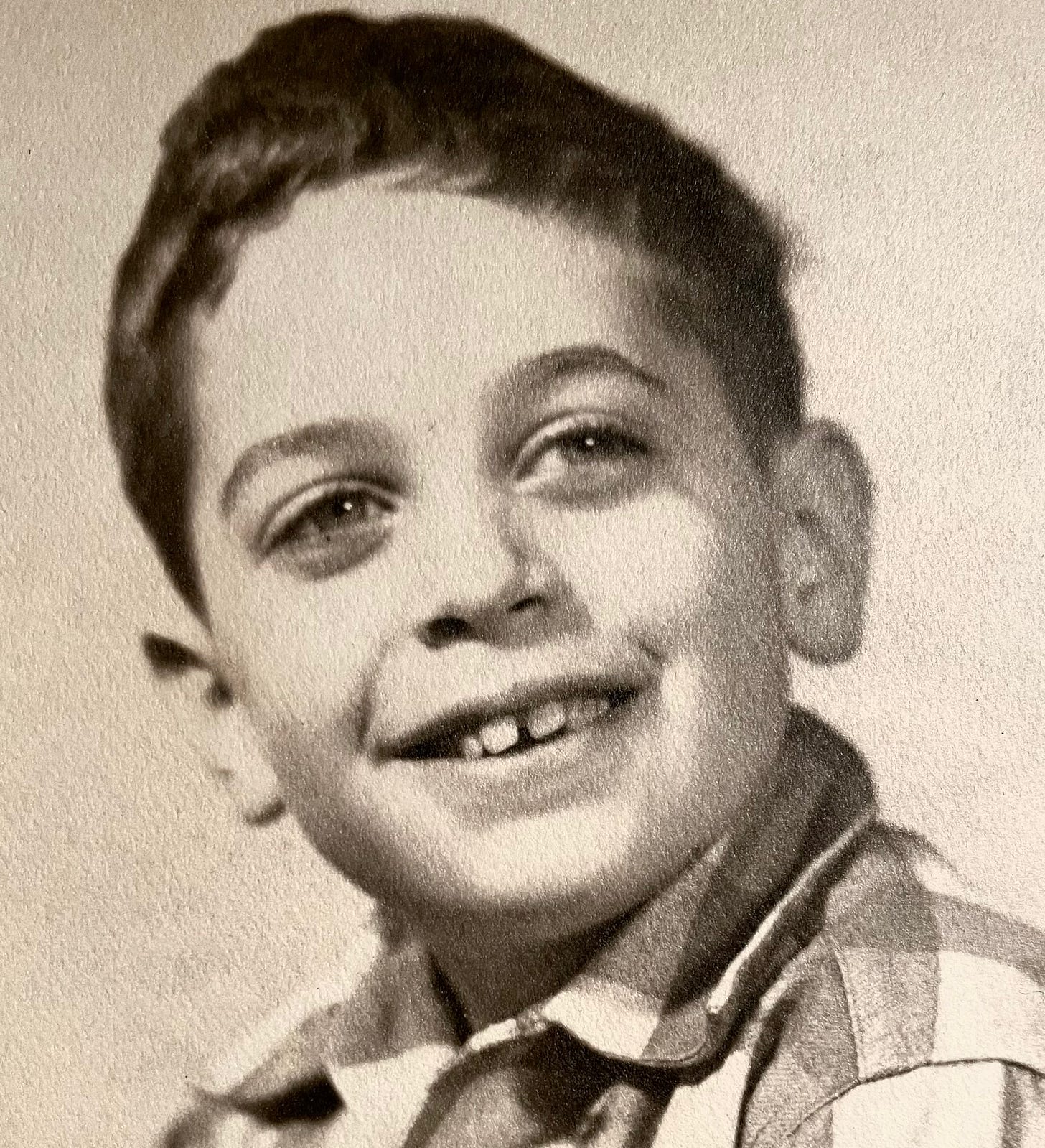

I arrived in Mrs. Camp’s third-grade classroom in Lewisboro Elementary School, in South Salem, New York, as an extremely short, shy, insecure 8-year-old who was often bullied and mocked on the bus and made to feel like a loser on the playground and had no particular interest in school.

But she saw in me something I didn’t see. She fed me books, projects, ideas. She challenged me and praised me. She made me feel special. Her slightly whacky sense of humor connected with mine. Her curiosity fueled mine (she didn’t mind if I stayed in at recess and barraged her with questions). Her enjoyment of literature made it okay for me to love books.

She made me understand that I wasn’t a freak, that I might even be talented, that the drawings and writings I did (up until then alone at my small desk in my bedroom) were okay — perhaps even good. And there was no reason for me to be so sad and ashamed, so fearful, so alone in the world.

I think of Mrs. Camp when I see America’s teachers blamed these days for almost everything imaginable — yelled at by parents over masks, reprimanded by school boards about books they assign or let their students read, vilified by politicians for teaching about America’s history of racism, even told to arm themselves against the possibility that their classrooms will be invaded by murderous young men with semi-automatics.

That’s wrong.

Instead of berating our teachers, we should honor them. Instead of imposing ludicrous demands on them we should free them to teach and inspire. Instead of demeaning them we should express our gratitude to them — every day.

And we should pay them twice as much as they’re now earning, or three times.

Did you know that 94 percent of America’s teachers have had to dip into their own pockets to buy school supplies? This, at a time when the average Wall Street employee bonus for 2021 hit $257,500.

Why in hell should investment bankers get paid fortunes for moving money from one set of pockets to another, when our teachers can barely afford to live on what they make? Bankers watch over our financial capital. Teachers watch over our human capital — and therefore our future.

I don’t think there’s a “teacher shortage.” I think there’s a shortage of teaching jobs that treat educators with the dignity — and give them the pay — they deserve.

I never saw Alice Camp again after third grade ended for me that June of 1954. I never had a chance to thank her (although I do remember sitting cross-legged on the floor at the end-of-year school assembly, quietly crying about leaving her and trying desperately not to show it).

She passed away long ago.

I had the great fortune to have other wonderful teachers over the rest of my years of public elementary and high school, and then in college and graduate school. I don’t recall thanking any of them, either. Most are gone by now. But I think of them often. And I am forever in their debt.

I suppose one way I’ve managed to pay back a small portion of that debt is to teach — which I’ve done for most of the last forty years. I love teaching. I love my students. I can’t imagine a more rewarding or noble profession.

When I expressed my appreciation of America’s teachers last June, and of Alice Camp in particular, I received lots of emails thanking me. Among them was a lovely letter from one of Mrs. Camp’s sons. He wrote:

I want to thank you for your moving tribute to my mother, Alice Camp. It brought tears to my eyes because you so completely nailed who she was.

She loved teaching. She spent endless hours at home after school working on projects and lesson plans and so on. To the point of exhaustion it seemed. For she did all the "single mom," work, too.

She was deeply interested in her "kids" and not just the best and brightest such as you but equally the troubled, the disadvantaged, the ones who struggled. My mother was all about justice and fairness. …

I could go on, but let me again on behalf of myself, my brother and sister (and my kids, because they all know the story, too) thank you for your loving words about Alice. She was my hero.

Share this post