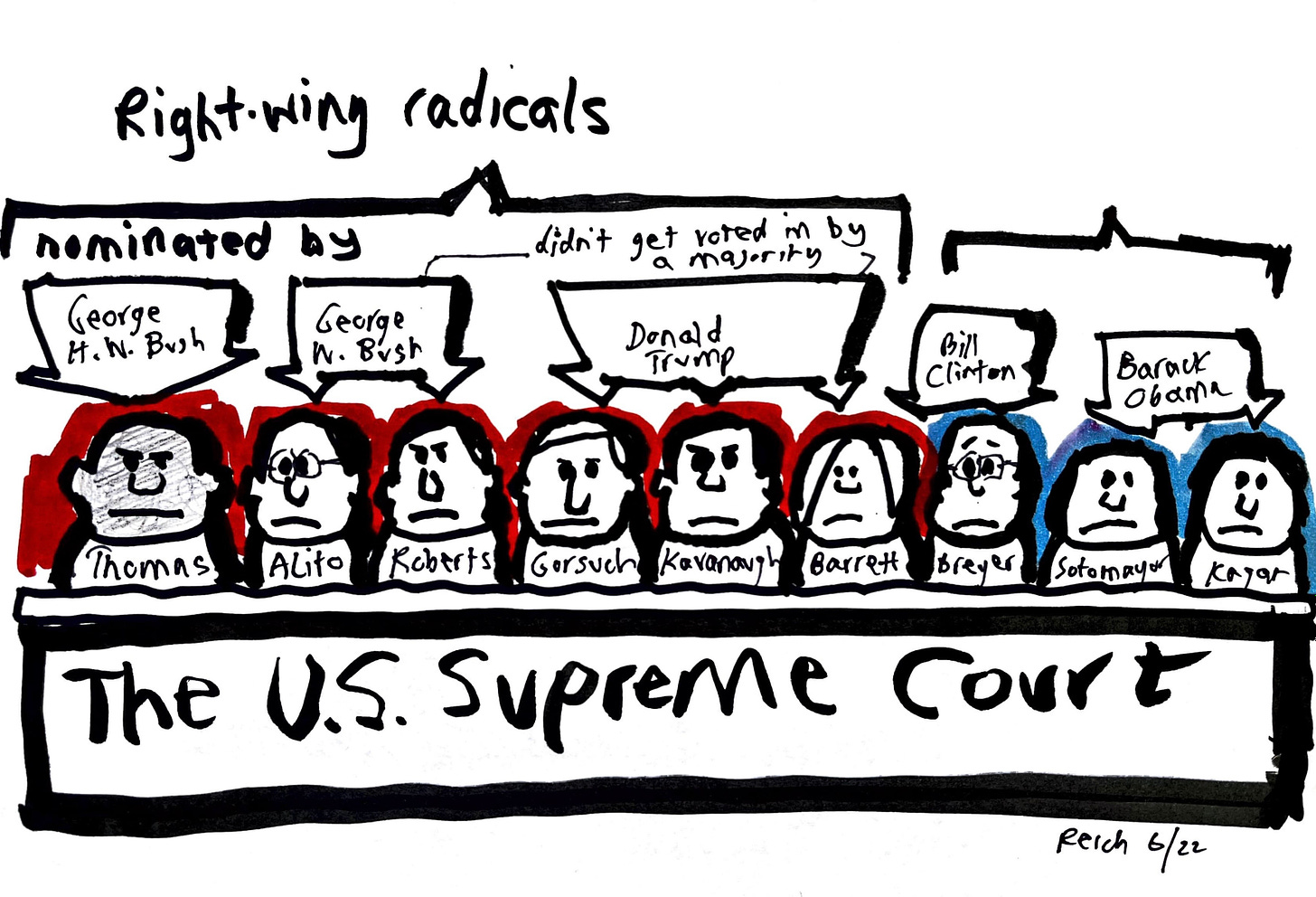

If there’s any doubt about the extremism of the Supreme Court’s six Republican appointees, it was on full display today with their opinion in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overrules Roe v. Wade, establishing the right to an abortion. Roe had been the law of the land for almost fifty years.

Even more ominous is Clarence Thomas’s concurring opinion, in which he argues that the same rationale the court used to overrule Roe should be used to overturn cases establishing rights to contraception, same-sex consensual relations and same-sex marriage. Thomas is pointing the way for the radicals on the court to take in the future.

If the due process clause of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution doesn’t protect abortion, says Thomas, the court “should reconsider” other cases that rely on the same clause: Griswold v. Connecticut, a 1965 decision that declared married couples have a right to contraception; Lawrence v. Texas, a 2003 case invalidating sodomy laws and making same-sex sexual activity legal across the country; and Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 case establishing the right of gay couples to marry.

Thomas says the court has a duty to “correct the error” established in those precedents. That’s not all. After “overruling these demonstrably erroneous decisions, the question would remain whether other constitutional provisions” protected the rights they established, says Thomas.

I was in law school in 1973 when the Supreme Court decided Roe v Wade. Also in my class at the time was Clarence Thomas, along with Hillary Rodham (later Hillary Clinton) and Bill Clinton.

As I’ve noted before, our law professors used the “Socratic method” – asking hard questions about the cases they were discussing and waiting for students to raise their hands in response, and then criticizing the responses. It was a hair-raising but effective way to learn the law.

One of the principles guiding those discussions is called stare decisis — Latin for “to stand by things decided.” It’s the doctrine of judicial precedent. If a court has already ruled on an issue (say, on reproductive rights or gay marriage), future courts should decide similar cases the same way. The Supreme Court can change its mind and rule differently than before, but it needs good reasons to do so, and it helps if the justice’s opinion is unanimous or nearly so. Otherwise, the rulings appear (and are) arbitrary — even, shall we say? — political.

In those classroom discussions almost fifty years ago, Hillary’s hand was always first in the air. When she was called upon, she gave perfect answers – whole paragraphs, precisely phrased. She distinguished one case from another, using precedents and stare decisis to guide her thinking. I was awed.

My hand was in the air about half the time, and when called on, my answers were meh.

Clarence’s hand was never in the air. I don’t recall him saying anything, ever.

Bill was never in class.

Only one of us now sits on the Supreme Court. He and five of his colleagues — all appointed by Republican presidents, five by presidents who lost the popular vote, three by a president who instigated a coup against the United States — are now violating stare decisis. They have not given a clear and convincing argument for why. Thomas wants the court to reverse more than a half century of rights.

The Supreme Court is now firmly in the hands of radicals, eager to throw stare decisis out the window. They are part of the anti-democracy movement now threatening America.

The shame of the Supreme Court