Hello again, friends.

After pro-choice protesters showed up outside the homes of Justice Samuel Alito and two other justices — peacefully chanting while walking in the street that lacked sidewalks — the editorial board of the Washington Post described such protests as “problematic” because they “bring direct public pressure to bear on a decision-making process that must be controlled, evidence-based and rational if there is to be any hope of an independent judiciary.”

I’m sympathetic to this view. It’s one thing to picket the Supreme Court as an institution; it’s quite another to demonstrate in front of the homes of individual justices. But surely the pro-choice protesters have a First Amendment right to be heard. I’m reminded of a 1994 case (Madsen v. Women’s Health Center, Inc.) in which the Supreme Court upheld the First Amendment rights of anti-abortion protesters to picket the residences of employees of an abortion clinic, saying the ordinance barring such protests within 300 feet of such residences was too broad.

The underlying question is how to weigh the First Amendment rights of protesters against the privacy rights of individual justices. The irony, of course, is that Justice Alito’s leaked opinion finds no right to privacy in the Constitution.

***

Alito’s leaked decision has led me to reflect back on my years briefing and arguing cases before the Supreme Court almost fifty years ago. The Court I argued before understood that its role was to balance the scales of justice in favor of the powerless. The two political branches of government (Congress and the executive branch) could not be relied on to do this.

Republican appointees to the Supreme Court understood this role as did Democratic appointees. Even Richard Nixon’s appointees — Harry Blackmun, Lewis Powell, and Warren Burger — exemplified this. It was Blackmun who wrote the Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, and Powell and Burger joined him, as did four Democratic appointees to the Court — William O. Douglas, Thurgood Marshall, William Brennan, and Potter Stewart.

The cases I argued were insignificant. I was a rookie in the Justice Department who was given either sure winners or sure losers to argue because the Department didn’t want to take a risk on a rookie — a wise move. (At my first argument, I mistakenly referred to Justice Stewart as Justice Brennan, which caused the two of them to guffaw and me to be mortified.)

But I was in awe of that Court.

I especially recall Douglas, who had recently suffered a stroke and was in obvious discomfort, looking sharply at me as I made my arguments. Here was the justice who wrote the 1965 decision in Griswold v. Connecticut, finding that a constitutional right to privacy forbids states from banning contraception — a right that would be jeopardized by Samuel Alito’s current analysis because, again, Alito doesn’t recognize a privacy right in the Constitution.

Douglas was also the man who decided that the Vietnam war was illegal and issued an order that temporarily blocked sending Army reservists to Vietnam. He was the justice who wrote in the 1972 case Sierra Club v. Morton that any part of nature feeling the destructive pressure of modern technology should have standing to sue in court — including rivers, lakes, trees, and even the air — because if corporations (which are legal fictions) have standing, shouldn’t the natural world?

Sitting not far away from him on the bench was Thurgood Marshall — who two decades before had succeeded in having the Supreme Court declare segregated public schools unconstitutional, in the 1954 landmark Brown v. Board of Education. Marshall did more than any person then alive to break down the shameful legal edifice of Jim Crow.

Douglas, Marshall, and Blackmun were the intellectual leaders of that Supreme Court. Their opinions gave the Court its moral heft. They drew not only from the Constitution as written but also from the nation as it had evolved. They understood the moral leadership America needed to protect the rights of the voiceless and the powerless.

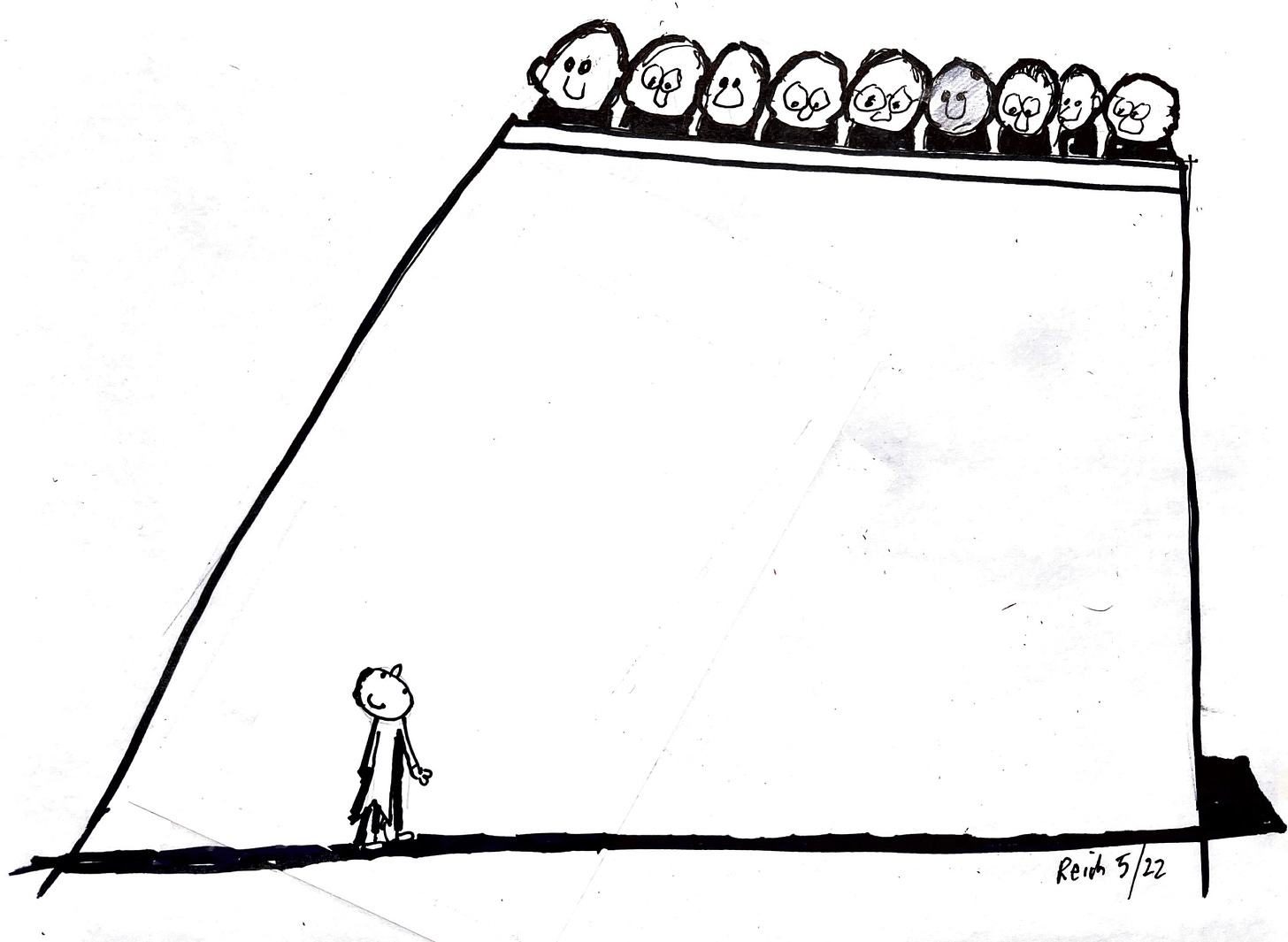

Today’s Supreme Court majority doesn’t have a clue about the Court’s moral authority, and couldn’t care less. They are political hacks, rigid ideologues, and small minds intent on entrenching the power of the already powerful, comforting the already comfortable, and inflicting pain on the already inflicted. (Five were nominated by presidents who lost the popular vote. Three were nominated by a president who instigated a coup against the United States; they were confirmed because a rogue Republican Party mounted scorched-earth campaigns to put them on the Court.)

The intellectual leader of today’s majority (if “intellectual” is the appropriate adjective) is Samuel Alito, perhaps the most conceptually rigid and cognitively dishonest justice since Chief Justice Roger Taney (who authored Dred Scott v. Sanford in 1857, finding that Congress had no power to exclude slavery from the territories and that Black people could not become citizens).

The authority of the Supreme Court derives entirely from Americans’ confidence and trust in it. As Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers No. 78, the judiciary has no influence over “the sword” (the executive branch’s power to compel action) “or the purse” (the Congress’s power to appropriate funds). The Supreme Court I was privileged to argue before almost 50 years ago had significant moral authority. It protected the less powerful with arguments that resonated with the core values of the nation. Americans didn’t always agree with its conclusions, but they respected it. That respect and trust allowed the Court to lead the way, charting a moral course for the nation.

Today’s cruel and partisan Supreme Court majority is squandering what remains of the Court’s moral authority. That is perhaps the deepest tragedy of all.

Share this post