These are hard times to keep your spirits up. Thinking you might need a bit of a boost, I’d like to introduce you to two young people who give me hope about the future of American politics.

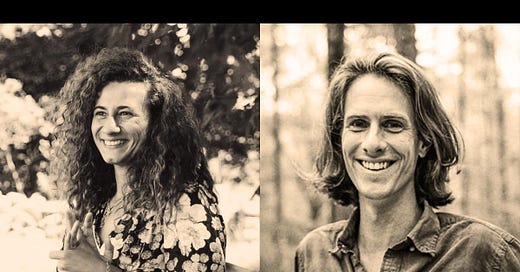

The first is Chloe Maxmin. I met her a few years ago when, still in her early-twenties and an unapologetic progressive, she had been elected to the Maine House of Representatives. She was the first Democrat ever to represent her district — Maine’s Lincoln County, the state’s most rural. The county also among the poorest, where 1 in 5 children grow up in poverty. And it’s staunchly conservative, having voted Republican by an average of 16 percentage points in the preceding three elections.

When I met her, Maxmin was preparing to run for the state Senate. Several old Maine pols (I lived in Maine back in the last century and know its politics quite well) told me she didn’t stand a chance. But in 2020 she won — and in the process, knocked off the state Senate’s Republican leader, the most powerful Republican politician in Maine.

How did she pull off these upsets? I’ll get to that in a moment.

Maxmin exudes optimism, energy, and tenacity. She is also very smart. She says she’d always imagined running when she was in her thirties. She thought she needed a couple of graduate degrees, a settled life, and maybe a family to welcome her home. But in 2018, as the climate crisis worsened, she realized there was no need and no time to wait.

The second person I’d like to introduce you to managed both her campaigns. Canyon Woodward was brought up in a rural part of Southern Appalachia. Maxmin and Woodward met each other in college and decided that the only way to begin solving the climate crisis and the injustices it was spawning was to get involved in politics from the ground up. Both had watched for years as rural America was abandoned by Democrats. They decided to buck that tide.

So, how did Maxmin and Woodward do it? They developed the most grass-roots of all grass-roots strategies.

Maxmin herself knocked on tens of thousands of doors. She connected with persuadable Trump voters who had never before spoken with a Democratic candidate. But she didn’t just talk to them. She had conversations with them, then followed up with more conversation. Those conversations were about “kitchen-table” issues — problems that were on the voters’ minds, as well as their thoughts and values.

As she describes it, during her campaign for the Maine House she walked down a dirt road leading to a nondescript trailer. After knocking on the door, it cracked open to reveal a man who was reluctant to hear from her. She introduced herself nonetheless and asked him about the issues he cared about most in the coming election. After they talked for a time, he told her: “You’re the first person to listen to me. Everyone judges what my house looks like. They don’t bother to knock. I’m grateful that you came. I’m going to vote for you.”

When I asked about her approach to politics, Maxmin told me rural communities are moral communities that respond more to personal stories and values than to specific policies. Building trusting relationships is the key. This takes time and effort and demands humility and a willingness to learn. As Maxmin and Woodward explain in their book, Dirt Road Revival: How to Rebuild Rural Politics and Why Our Future Depends On It (to be published in March):

“Things move at the speed of relationship in rural America. You don’t jump straight into business and take care of things as quickly as possible. An essential part of the culture of living and organizing in rural America is slowing down and building relationships. It is the touchstone on which our future—and all hope of transforming how we relate to politics and one another—depends. And a good relationship starts with a handshake. This small gesture is about establishing a modicum of trust and human connection. To show up, look someone in the eye, and shake their hand is to plant the seeds of possibility and connection. It’s also what is lacking in today’s politics. A voter told us one day, “I don’t identify with either party. I vote for the person. I vote for whoever has the firmest handshake.”

Maxmin has already got a “green new deal” bill through the legislature. She’s well on her way to being one of the nation’s most effective state legislators on climate justice.

What’s the larger political picture here? The Democratic Party’s abandonment of rural America has proved a strategic mistake. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won almost every urban center, but Trump swept the vast stretches of less populated country in between. Exit polling revealed that Trump won nearly two-thirds of the rural vote, while losing by a similar margin in cities and evenly splitting the suburban vote.

When the American electoral system was created, over 95 percent of Americans lived in rural communities. Now, fewer than 20 percent do. But the nation’s electoral system remains locked in the founders’ two eighteenth century inventions — both of them premised on America’s widely-dispersed rural population: the Electoral College, and a Senate in which each state gets two senators.

As Americans have clustered in megalopolises along the East, West, and Gulf coasts, the Electoral College has become increasingly unrepresentative. Democratic presidential candidates have won the popular vote in seven out of the past eight elections dating back to 1988, but the Electoral College has elected Republican candidates in three of them.

The same power imbalance is now reflected in the Supreme Court, where Republican presidents who failed to win the popular vote have appointed five of the nine sitting justices.

The Senate is also becoming less and less representative of America. Today, the ten most populous states in the union are home to half the US population, but their twenty senators make up only a fifth of the US Senate. The other half of the population, spread out over forty smaller states, elects four-fifths of the Senate. This means half of the country gets four times the number of US senators per person as the other half. A state like California, with 40 million people, has the same number of senators as Wyoming, with 579,000.

It will be many years (if ever) before these anachronisms are remedied. Entrenched power doesn’t easily yield to reform.

So as a practical matter — at least in the foreseeable future — the only way Democrats can retain and enlarge their political power is by winning over more of rural America. Maxmin and Woodward are charting the way.

Share this post