Friends,

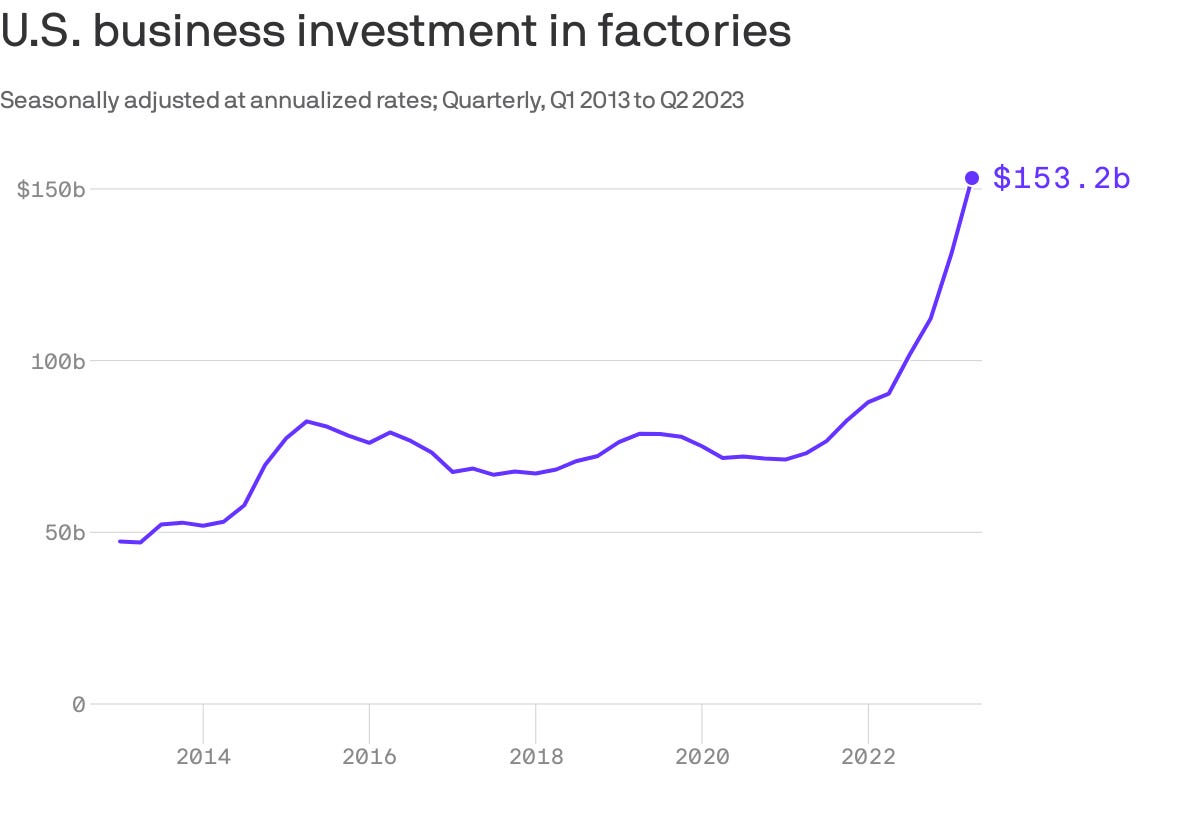

Lost in the tremors of the Trump indictments has been an extraordinary economic fact. The Biden administration is bringing back American manufacturing. It’s one of the most significant (and least publicized) economic stories in recent decades (see chart).

Industrial policy is making a comeback. Good manufacturing jobs are coming back. But will America even notice amidst the earth-shaking charges against Trump, and Trump’s (and his enabler’s) wild counter charges?

***

Joe Biden’s remarkable industrial policy success:

[Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Chart: Axios Visuals]

***

I’m reminded that thirty-eight years ago tomorrow (on August 4, 1985), I wrote an op-ed for The New York Times in which I pointed out that Ronald Reagan had launched a wildly ambitious industrial policy to shrink older industries and thrust America into high-tech industries of the future. But I warned that it was too ambitious — that it would phase out old manufacturing industries and jobs too quickly and that the human toll would be too great, and Reagan’s new industrial policy would fail.

The op-ed caused a storm of protest. I was inundated with irate phone calls and letters (this was before email and social media).

Reagan Republicans were livid that I dared even suggest Reagan was using the heavy hand of government to “pick winners and losers.” Centrists were upset that I was continuing to advocate an industrial policy, after having pushed several Democrats who had sought the presidency in 1984 to adopt aspects of it. Democrats were angry that I appeared to support something Reagan was doing (in fact, I was being ironic).

Given that the Biden administration has now actually launched what appears to be an enormously successful industrial policy, I thought you might enjoy reading my op-ed from 38 years ago. Herewith.

REAGAN’S HIDDEN INDUSTRIAL POLICY

NOT LONG AGO, several Democratic Presidential aspirants were talking about industrial policy. Although the precise meaning of the term remained elusive, the general idea was that the Government should be more purposeful in easing the transition of our economy out of basic industries like steel and textiles into high-tech businesses.

The argument was that without an explicit industrial policy - encouraging our older industries to reduce outmoded capacity and adapt newer technologies, channeling research and development funds to emerging industries and helping workers retrain - the changes would come slower and be more painful, and in the meantime the United States would have lost out to other nations that had made the transition more smoothly (notably, Japan).

The term ''industrial policy'' has fallen out of fashion, largely because the Democrats lost the election but also because the economic recovery of 1983 and 1984 suggested that there was no problem to begin with.

The idea also went against the ideological drift of the times. The thought that Government should take a role in shifting economic resources smacked of central planning, and conjured up all the forbidden ''isms.'' Anyway, how could the Government competently pick winners and losers? Wouldn't the whole program just end up being another trough at which the special interests fed?

It has taken a concerted effort by Ronald Reagan to rehabilitate the idea of industrial policy. To be sure, the term appears nowhere in his oratory. But his major policies are showing that Government can play an active role in transforming the economy from ''sunset'' industries to ''sunrise.'' His three-step plan is a more ambitious industrial policy than the Democrats ever dreamed of proposing. Consider:

Shrinking basic industry.

Standardized goods, such as basic steel, autos, textiles, commodity chemicals and others that rest on mass or large-batch production are particularly vulnerable to price competition. Thus, the easiest way to reduce their size is to increase their price in world markets - thereby making it difficult for them to export and making it relatively easy for foreign producers to threaten them at home. And the fastest way to increase their price is to raise the value of the dollar by running huge budget deficits. Presto: these industries are forced to contract.

The Reagan plan to shrink America's basic industries has been enormously successful. Since 1981, when the value of the dollar began climbing to unprecedented levels as the budget deficit ballooned, some 2 million jobs have been lost in old-line manufacturing businesses. Steel, autos and others have been forced to reduce domestic capacity, set up operations abroad (or enter into joint ventures with foreign producers) and diversify into specialized niches.

Finishing off basic industry.

Once they have been crippled by international trade, it is a relatively small matter to finish off ''sunset'' industries altogether. This would be accomplished with the passage of a new tax-simplification plan, which as proposed would eliminate any lingering incentives to invest in America's older industrial base.

The Reagan tax-revision proposal would end the investment tax credit, which has been worth approximately $25 billion a year - particularly to older, capital-intensive industries in need of modernization. The proposal also would reduce the pace at which plant and machinery could be depreciated; the present accelerated schedule has resulted in billions of extra dollars being channeled into basic industries, some of which have ''sold'' the tax breaks for needed cash. All told, the Reagan tax plan would rescind more than $200 billion of such tax benefits, which have proved critical to ''smokestack'' America.

Promoting high tech.

America's emerging industries - advanced computers, lasers, fiber-optics, new materials, biotechnologies and so on - will benefit both from the lower rates in the new tax proposal and from its retention of the tax credit for research and development.

But more important to high tech is President Reagan's military buildup. Since 1981, about $400 billion has been channeled into new weapons - most depending on advanced technologies. This demand for state-of-the-art products has pulled these emerging industries down the ''learning curve'' to the point where commercial spinoffs are attainable.

Mr. Reagan would like another $400 billion for advanced weapons between now and 1990. At the same time, well over 60 percent of all the research and development funds for America's high-technology industries is coming directly from the Pentagon. President Reagan's ''Star Wars'' proposal would channel an additional $26 billion into these future technologies over the next five years.

Viewed as a whole, Mr. Reagan's budget deficit, tax plan and military buildup comprise an extraordinarily ambitious plan for shifting America's industrial base. This is industrial policy with a vengeance. But because Mr. Reagan is who he is - avowed defender of the free market from the depredations of big government -there are no voices to his right, vigorously denouncing Washington's vulgar intrusion into the temple of the marketplace. As only Richard Nixon could open relations with Peking, so only Ronald Reagan can make economic planning respectable.

But the President's industrial policy may be too ambitious. The collapse of America's basic industries is throwing off far more blue-collar workers than can be reabsorbed into other high-paying jobs, even during the recent years of record growth. What happens at the next downturn in the economy?

And our limited supply of scientists and engineers is straining high-tech industries' capacity to meet military needs and at the same time stay commercially competitive. What's missing from President Reagan's industrial policy is a plan for helping our work force adapt to the shifts under way - through retraining, relocation and education and day care for the kids while the two careers adjust.

The plan is also risky. Such a broad leap from older industries to new carries a danger that the new ones will not be able to sustain our standard of living on their own. Even at best, how many good jobs will high tech deliver? And what happens if the bottom falls out of these fashionable technologies, as seems to be happening to personal computers of late?

A more gradual, responsible industrial policy would not force us to move so convulsively from ''smokestack'' to high tech but would help put high technologies into our older industries - and simultaneously upgrade workers' skills to handle the new manufacturing processes - so as to render the entire industrial base more competitive.

Ronald Reagan's industrial policy is a major experiment in economic planning. Ironically, it may yet prove the wisdom of Mr. Reagan's own rhetoric - that it cannot be done, at least not with such a heavy hand.

***

Professor

Thank you for this, and more importantly for you life of work on behalf of part of my chosen family.

As is often the case, I wake up in the middle of the night and turn on my computer and find your comments.

The industrial policy followed by Regan was wrong then, and the industrial policy being followed today in the USA is wrong now. I am reading Matthew Desmond’s recent book "Poverty, by America"

He believes that entrenched poverty in the United States is the product not only of larger shifts, such as deindustrialization and family dissolution, but of choices and actions by more fortunate Americans. Poverty persists partly because many of us, with varying degrees of self-awareness, benefit from its penetration. “It’s a useful exercise, evaluating the merits of different explanations for poverty, like those having to do with immigration or the family,” Desmond writes. “But I’ve found that doing so always leads me back to the taproot, the central feature from which all other rootlets spring, which in our case is the simple truth that poverty is an injury, a taking. Tens of millions of Americans do not end up poor by a mistake of history or personal conduct. Poverty persists because some wish and will it to.”

H e reminds us that "Poverty isn’t simply the condition of not having enough money It’s the condition of not having enough choice and being taken advantage of because of that.” He suggests "Becoming a poverty abolitionist, entails conducting an audit of our lives, personalizing poverty by examining all the ways we are connected to the problem — and to the solution.”

I am conducting an audit of my life. I hope some of you will join me.

Pretty much spot on in your predictions even if you were being tongue in cheek. Guess the explosion in tech jobs did insure American prosperity for those workers but not the traditional hard hat blue collar middle class . And that undercut the importance of unions in the economy.