Friends,

From time to time, I offer some personal history, because you may have an interest in where my values and perspectives come from and how what I’ve experienced sheds light on what we’re dealing with now.

So today I want to talk to you about what was known as the New Left, which I discovered (and embraced) as a teenager in the 1960s.

By then, the labor union movement — the heart of the Old Left — was viewed as history. Although my mother’s stepfather (whom I never knew) had been a union lawyer, and my mother’s mother — my grandma Frances — was an activist firebrand, no one spoke of the labor movement as a contemporary phenomenon.

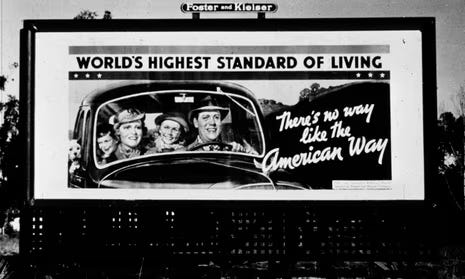

The Old Left had faded as a result of Joe McCarthy’s red scare, labor leaders’ concerns about being seen as communist or socialist, and the effects of the anti-union Taft-Hartley Act of 1947. It also faded because soaring prosperity and the remarkable growth of the middle class seemed to make the Old Left irrelevant.

The Old Left had focused on material concerns such as employment, wages, pensions, and job security. It had sought to give the working class a larger slice of the economic pie.

The New Left focused on the needs of people fortunate enough to take material comfort for granted — mostly college students, college graduates, and professionals. It sought to protect consumers from unsafe products, reduce pollution, win new rights for women and people of color, reduce dire poverty, and spread participatory democracy.

My introduction to the New Left was the “Port Huron Statement,” issued by a group of mostly white, middle-class college students from the University of Michigan. Its main author was a young activist named Tom Hayden, a recent graduate of the University of Michigan and editor of the Michigan Daily, who was then just 21 years old. Hayden went on to become president of Students for a Democratic Society.

A friend had lent me a copy. I read it in the summer of 1963 on the front porch of my grandma Frances’s cottage in the Adirondack Mountains.

From its very first line, I was transfixed. “We are people of this generation,” it read, “bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.”

It seemed to be talking directly to me. I wasn’t yet in college but was planning to choose one that fall. And although reared in modest comfort, I felt increasingly uncomfortable with the direction America was taking.

Segregationists and white supremacists seemed to be on the rise in reaction to the Civil Rights Movement. Martin Luther King Jr. was then leading a March on Washington for social and economic justice. The previous fall’s Cuban missile crisis had brought the world perilously close to a nuclear holocaust. Vietnam was already becoming a quagmire. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring warned that pesticides and other toxins put into the environment were having devastating effects. My mother saw herself in Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, which described suburban housewives trapped in “dependent, passive, childlike” roles.

The Port Huron Statement criticized America’s foreign policy, centered on a nuclear arms race that heightened the risk of nuclear war. It challenged the nation’s faith in technology, affluence, and materialism — an American Dream that encouraged consumerism and conformity. “The goal of man and society should be human independence: a concern not with … popularity but with finding a meaning in life that is personally authentic …. This kind of independence does not mean egotistic individualism — the object is not to have one’s way so much as it is to have a way that is one’s own.”

And it took on university education, asserting that:

“…our experience in the universities [has not] brought us moral enlightenment. Our professors and administrators sacrifice controversy to public relations; their curriculums change more slowly than the living events of the world; their skills and silence are purchased by investors in the arms race; passion is called unscholastic …. The questions we might want raised — what is really important? can we live in a different and better way? if we wanted to change society, how would we do it? — are not thought to be questions of a ‘fruitful, empirical nature,’ and thus are brushed aside.”

In response to all these failings, the Statement called for participatory democracy — across college campuses, in the South, and in inner cities. Seeing the effectiveness of the young civil rights protestors of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the authors believed that ordinary citizens — particularly students — could create change through nonviolent means.

It was the most specific and ambitious manifesto I had ever read (with the possible exception of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s Communist one) — proposing an “agenda for a generation.” At just over 25,000 words, it was also the longest.

It was eloquent — combining existential longings inspired by Albert Camus, a quote from an encyclical by Pope John XXIII, urgent descriptions of the most serious issues facing humankind (then known as “mankind”), and far-reaching, detailed proposals for how to go about the prodigious task of democratizing the nation and the world.

I adopted it as my manifesto.

I came to believe that university students and intellectuals were the vanguard of progressive change in America and the world. And that students such as those who drafted the Port Huron Statement would lead such changes.

In subsequent years I saw college students such as Mickey Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney as the ground troops of the Civil Rights Movement. I believed students like Mario Savio and others at Berkeley were responsible for guarding freedom of speech. And that other students, such as those I would recruit for Gene McCarthy’s presidential campaign, would end the Vietnam War.

But I had left out a big portion of America — the non-college working class.

By the mid-1960s, fewer than 10 percent of Americans had graduated from a four-year university.

Even now, more than 50 years later, only 40 percent of adult Americans have a four-year college degree.

I wasn’t the only one overlooking the vast majority of Americans lacking college degrees. The New Left had relegated the depredations and indignities of class — and the need for strong labor unions to lift workers’ wages, protect jobs, provide pensions, and give workers some modicum of job security — to the backwater of activism.

By the late 1960s, the American middle class had expanded beyond anyone’s imaginings. It seemed as if almost all Americans, apart from the very poor, were on the way to enjoying the comforts of modern life. Many working-class people were satisfied with their rising standard of living.

As my future mentor and friend John Kenneth Galbraith wrote in The Affluent Society, published in 1958, America had become a society of abundance.

As I saw it then, the problem was drab conformity, crass materialism, and the hypocrisy of American ideals — as illustrated in the 1967 film “The Graduate,” where Dustin Hoffman, playing Benjamin Braddock, a newly minted college graduate, is told that the future is in “plastics” and is seduced by the mother of the girl he loves.

Like Tom Hayden and the students who produced the Port Huron Statement, the trail-blazing progressive authors of the 1960s barely mentioned the working class.

Betty Friedan’s 1963 classic, The Feminine Mystique, grew out of a 15th reunion survey at Smith College, and its message that women should join the workforce was of little relevance to working-class women already there.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring spurred the environmental movement. Ralph Nader’s 1965 bestseller, Unsafe at Any Speed, gave birth to the consumer movement. Michael Harrington’s 1962 eye-opener, The Other America, exposed American poverty and inspired Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty.

But the labor movement was all but forgotten.

Not even Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society aimed to strengthen and expand the rights of workers. (Initially Johnson intended to repeal part of the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 that allowed so-called open shops, but Johnson backed off when corporate lobbyists attacked the proposed repeal.)

By the time I became secretary of labor, the Democratic Party was focusing its efforts on what were then called “suburban swing” voters — mostly college-educated professionals who tended to be liberal on social issues and more conservative on economic ones.

Labor unions were still part of the Democratic Party but of diminishing importance; the percentage of unionized workers in the private sector had fallen precipitously from over a third in the 1950s to around 10 percent in the 1990s. Most union presidents were more interested in protecting the jobs of their existing members than expanding membership.

By the 1990s, America no longer had a mass movement centered on lifting most Americans’ living standards. It had what remained of the Civil Rights Movement, the women’s rights movement, the consumer movement, and the environmental movement, but no working-class movement.

Democratic presidents took organized labor for granted, if they thought about unions at all. When Jimmy Carter had to choose between a bill to strengthen labor unions or a treaty to hand over control of the Panama Canal to Panama, he chose the treaty, and the labor bill died. Bill Clinton didn’t push for labor law reform in his first two years of office, when Democrats held a majority in both houses of Congress. Nor did Barack Obama, under similar circumstances.

The consequence of all this was that by 2016, millions of American workers — the vast majority of them with no college education and no union to support them — had been left behind. Their wages were stagnant. They could be fired at will. Their lifespans were shrinking.

The economy no longer offered them the means of doing better. Politics no longer offered them a voice.

Into this void came Donald Trump, who as president gave large tax cuts to the wealthy and large corporations but somehow made the working class — especially the white working class — feel he was speaking to and for them.

He channeled their cumulative anxieties and frustrations into bigotry, nativism, and hate toward Muslims, Mexicans, Democrats, bureaucrats, and “coastal elites.” He took a wrecking ball to democracy. He is now running for president again.

"He (Donald Trump) took a wrecking ball to democracy." No truer words were said. And as you have pointed out so eloquently, Mitch McConnell is the one who paved the way so the wrecking ball could create the most havoc.

Everybody who works for a paycheck is in the same class, and the sooner we realize it, the sooner we can unite and move forward. There is no poor, working class, and low, middle, and upper middle class. Carving the majority up and making some believe they are superior to those economically below them keeps the majority from realizing it is a class war with only two classes; the majority of us against the tiny oligarch class. Everyone economically above the poor can participate in the game of victim blaming that keeps capitalism solidly within our culture. When we continue to falsely believe this is the land of opportunity, and that anyone can succeed if they work hard enough, we perpetuate the myth of capitalism. We sacrifice the potential for decent lives for everyone without excessive stress and anxiety, to the morbidly rich who have created a system that sucks wealth from the bottom to the top.

We're in this together.