Friends,

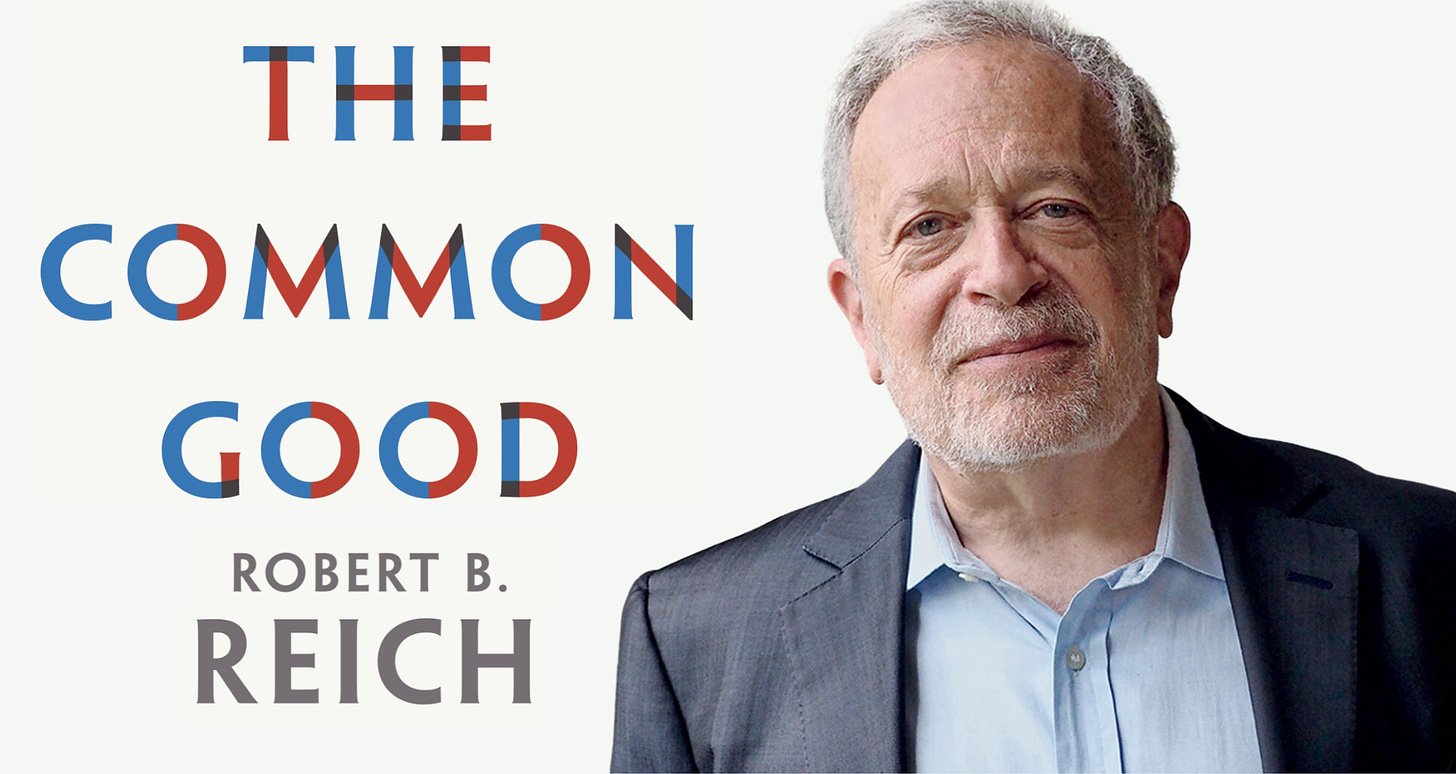

Of all the books I’ve written, the one that is closest to my heart is THE COMMON GOOD, which came out in 2018. Why? Because the common good recognizes that we’re all in this together. Instead of being self-seeking individuals who happen to live within the same political and geographic boundaries, we are a group of people with responsibilities to one another.

The theme of THE COMMON GOOD is more relevant today than ever. I urge you to read my book, along with these weekly essays based on its chapters (and here’s a link). In them, I will apply the framework of the book and its key themes to the events of the last few years, to illuminate the larger story that’s been unfolding and the reckoning that is coming.

We have come to an inflection point in the history of our lives together — both as Americans and as inhabitants of the world.

How we vote in the upcoming election of 2024 may determine whether American democracy survives.

How we respond to the excesses of this second Gilded Age — featuring levels of inequality and corruption not seen since the first one, a century ago — will help determine whether our economy and society survive.

How we deal with the accelerating climate crisis will determine whether human life on Earth survives.

All these turn on our understanding of the common good.

I was at the impressionable age of 14 when I heard John F. Kennedy urge us to ask not what America can do for us but what we can do for America.

Seven years later, I took a job as a summer intern in the Senate office of his brother, Robert F. Kennedy (whose son and namesake is now besmirching his memory). I ran the senator’s signature machine, but I told myself that in a very tiny way I was doing something for the good of the country.

That was a half-century ago. Is America a better place now than it was then?

Our lives are more convenient. Fifty years ago, there were no cash machines or smart phones. No internet. No streaming video. No Zoom calls. I wrote my first book on a typewriter.

Our jobs are different. I grew up with telephone operators, gas-station attendants, and people who took me up and down elevators. Most customers of my father’s clothing store were the wives of factory workers.

As human beings, we are as kind and generous as ever. We volunteer in our communities, donate, and help one another. We pitch in during natural disasters and emergencies. We come to the aid of individuals in need.

We are a more inclusive society than we were a half-century ago in that Black people, women, and LGBTQ+ people have legal rights they didn’t have then (although Republican legislatures are actively trying to shrink them, even as you read this).

Yet our civic life — as citizens in our democracy, participants in our economy, managers or employees of companies, and members or leaders of organizations —seems to have sharply deteriorated. We are bitterly divided. Racism, xenophobia, misogyny, and homophobia are more apparent. A cynical selfishness has infused many of our dealings with one another.

What we have lost is a sense of our connectedness to each other as Americans, and to our ideals. We’ve lost the essence of the America that John F. Kennedy asked us to contribute to.

I remember when the shift started.

In the late 1970s, Americans began talking less about the common good and more about self-aggrandizement. We went from the “Greatest Generation” to the “Me Generation.” From “we’re all in it together” to “you’re on your own.”

In 1977, motivational speaker Robert Ringer wrote a book that reached the top of The New York Times bestseller list. It was titled Looking Out for #1. It extolled the virtues of selfishness. The 1987 film “Wall Street” epitomized the new ethos in the character Gordon Gekko and his signature line, “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good.”

The last five decades have also been marked by growing distrust toward all of the basic institutions of American society: government, the media, corporations, big banks, police, universities, charities, religious institutions, the professions.

There is a wide and pervasive sense that the system as a whole is no longer working.

A growing number of Americans feel neglected and powerless. Some are poor, or Black or Latino. Others are white and have been on a downward economic escalator for years. Many in the middle feel stressed and voiceless. You may well be among them.

Whether we call ourselves Democrats or Republicans, liberals or conservatives, we share many of the same anxieties and feel much of the same distrust. Yet we no longer even discuss what we owe each another as members of the same society.

I am now a septuagenarian, and Donald Trump is again running for president.

In many ways, Trump epitomizes what has gone wrong. But as I hope to make clear, Trump is not the cause. He is a consequence — the logical outcome of what has unfolded over many years.

His election in 2016 was propelled by many of these same forces — widening inequalities, widespread anxieties, distrust toward our political and economic system. His candidacy in 2024 is built on them.

Say what you want about him, Trump has at least brought us back to first principles. Some presidents, like Ronald Reagan, got us talking about the size and role of government. Trump has got us talking about democracy versus tyranny.

Some presidents, like Bill Clinton, invited a discussion of how we can make the most of ourselves. Trump, by dint of his pugnacious character and the divisiveness he has fueled, raises the question of what connects us, of what we hold in common.

Is there a common good that still binds us together as Americans? That it’s even necessary to ask shows how far we’ve strayed.

Today, some think we’re connected by the whiteness of our skin, or our adherence to Christianity, or the fact that we were born in the United States.

I believe we’re bound together by the ideals and principles we share and the mutual obligations those principles entail. We’re bound together by a common good that we once took for granted but must now rediscover and reassert.

My hope is that the following chapters — which I’ll be sharing with you over the next 10 Fridays — provoke a discussion of the good we have had in common, what has happened to it, and what we might do to restore it.

I urge you to add your comments, take part in our discussion, and share with others.

My goal is not that all Americans agree on the common good. It is that we get into the habit and practice of thinking and talking about it and hearing one another’s views about it. This alone would be an advance.

I should clarify from the start what this book is not. It is not about communism or socialism, although in this fractious era I wouldn’t be surprised if the word “common” in the title causes some people to assume it is.

It is not about what progressives or Democrats or Republicans ought to do to win in 2024 or beyond, what messages they should convey or policies they should propose. There is already quite enough political advice to go around.

And it’s not about Donald Trump and his campaign for reelection, although he does come up from time to time.

It is about what we owe one another as members of the same society — or at least what we did owe one another more than a half-century ago when I heard John F. Kennedy’s challenge.

It is about the good we once had in common — and, if we are going to preserve our democracy and equal opportunity and cope with existential threats like the climate crisis, must have again.

Thank you for joining me.

***

Subscribers to this newsletter are keeping it going. If you are able, please consider a paid or gift subscription. And we always appreciate your sharing our content with others and leaving your thoughts in the comments.

I think the critical discussion point concerns what it means to be an American. I mean, what is our nature? Is it in our Declaration of Independence, our Constitution, or our tax code? Or our Supreme Court rulings? I was brought up like you, Mr. Reich, believing in the common good and willing to sacrifice for it, by paying taxes or serving in the military. Vietnam changed my thinking, but I still happily paid up. Ronald Reagan did not merely make us think about the size of government; he in fact made us think that it was stealing from us. Unless, of course, it was spending our money with his pals in the California defense industry. I believe it was Ronald Reagan who truly divided us, after the Nixon schism ended in disgrace and we healed from the Vietnam disaster. Reagan demonized the needy, the workingman, and people of color. And he spit on the idea of the common good, extolling instead the virtues of self-reliance and personal aggrandizement. He helped promote the Trumpian idea that paying taxes was for fools. His assaults on our public lands continue to this day. 1980 was the turning point in American political culture. We are living with the vestiges of that rush to selfishness today.

Prof. Reich, this is the crux of all that is ailing the US. We, as a nation, need to get our compass heading adjusted - for the good of our children and families, our people, our communities, our country and our planet. I look forward to reading your book and your wisdom and guidance on how we all can help get us back on track.