Resurrecting the Common Good: A New (and Very Old) Conception of Leadership

Chapter 7 of The Common Good

Friends,

For the past six weeks, I’ve talked with you about how America lost its sense of the common good. Starting today and for the remaining four weeks of essays, I want to suggest what can be done to resurrect the common good.

Let’s begin with leadership. Too often, we lionize leaders who “win” — who are strong and tough enough to overcome rivals, who are ruthless and hard-hitting enough to generate huge profits, who are ferocious enough to beat all manner of competitors and thugs.

But leadership of the sort we need to resurrect the common good is not about winning. It’s not about being tough, ruthless, or ferocious. It’s about attending to the needs of the people who are being led — valuing and elevating the common good that binds them together. Earning and building their trust.

This must be the essence of leadership. We must demand it.

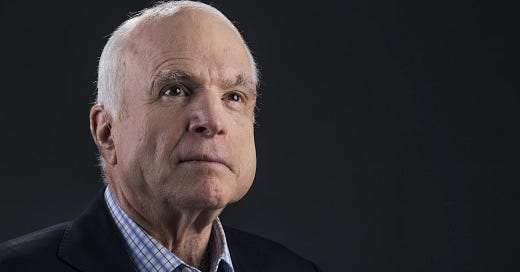

ON THE EVE of the Senate’s final vote on repealing the Affordable Care Act in July 2017, Senator John McCain returned to Washington from his home in Arizona, where he was being treated for brain cancer, to cast the deciding vote against repeal.

That was not the only thing he did. He took to the Senate floor to condemn the whatever-it-takes politics that had overtaken Washington.

McCain began by saluting a former generation of senators for whom the common good was more important than winning any particular legislative contest. “I’ve known and admired men and women in the Senate who played much more than a small role in our history, true statesmen, giants of American politics,” he said.

“They came from both parties, and from various backgrounds. Their ambitions were frequently in conflict. They held different views on the issues of the day. And they often had very serious disagreements about how best to serve the national interest. But they knew that however sharp and heartfelt their disputes, however keen their ambitions, they had an obligation to work collaboratively to ensure the Senate discharged its constitutional responsibilities effectively. . . . That principled mindset, and the service of our predecessors who possessed it, come to mind when I hear the Senate referred to as the world’s greatest deliberative body.”

McCain then admonished his current colleagues for eroding the common good, with words aimed as much at voters as at the senators. “Our deliberations today . . . are more partisan, more tribal, more of the time than any other time I remember,” he said. He reminded them that winning was not as important as upholding and strengthening the institutions of governing.

“Our system doesn’t depend on our nobility. It accounts for our imperfections, and gives an order to our individual strivings that has helped make ours the most powerful and prosperous society on earth. It is our responsibility to preserve that, even when it requires us to do something less satisfying than ‘winning.’ Even when we must give a little to get a little. Even when our efforts manage just three yards and a cloud of dust, while critics on both sides denounce us for timidity, for our failure to ‘triumph.’”

One of my fondest memories of McCain occurred in the 2008 presidential campaign, at a town hall event in Minnesota.

McCain responded to a supporter who said he was “scared” at the prospect of an Obama presidency. “I have to tell you,” McCain said, “Senator Obama is a decent person and a person you don’t have to be scared of as president of the United States.”

At this, the Republican crowd booed. “Come on, John!” one audience member yelled out. Others shouted that Obama was a “liar” and a “terrorist.” A woman holding a microphone said, “I can’t trust Obama. I have read about him and he’s not, he’s not uh — he’s an Arab. He’s not. . . .”

At that moment, McCain snapped the microphone from her hand and replied: “No, ma’am. He’s a decent family man [and] citizen that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues and that’s what this campaign’s all about. He’s not [an Arab].”

JOHN McCAIN exemplified a conception of leadership that’s now in short supply, but which the nation desperately needs — a leadership that prioritizes the common good and seeks to increase trust in our major institutions rather than undermine that trust for personal gain.

It is a form of leadership that America’s greatest presidents embodied — Washington, Lincoln, FDR. It is the leadership that the American experiment in self-government was based on.

McCain didn’t do everything right. He chose Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008 — a person whose belligerence and divisiveness foreshadowed that of Donald Trump. But McCain’s personal approach to leadership nonetheless eschewed “whatever-it-takes” politics.

AN AMERICAN PRESIDENT is not just the chief executive of the United States, and the office he (eventually she) holds is not just a bully pulpit to advance certain policy ideas.

The presidency is also a moral pulpit invested with meaning about the common good. The values a president enunciates and demonstrates ricochet through society, strengthening or undermining that common good.

In my view, Joe Biden has been a good president who has emphasized and elevated the common good. He should be reelected. In my view, Donald Trump should not just be convicted of the criminal charges against him. He ought to be condemned to the ash heap of history.

The damage Trump has done to the common good is incalculable.

In the 2016 presidential campaign, candidate Donald Trump was accused of failing to pay his income taxes. His response was, “That makes me smart.” Although not yet president, his comment conveyed a message to millions of other Americans that paying taxes in full is not an obligation of citizenship.

Trump also boasted about giving money to politicians so they would do whatever he wanted. “When they call, I give. And you know what, when I need something from them two years later, three years later, I call them. They are there for me.” In other words, it’s perfectly okay for business leaders to pay off politicians and for politicians to take their money, regardless of the effect on our democracy.

Trump sent another message by refusing to reveal his tax returns during the campaign, or even when he took office, or to put his businesses into a blind trust to avoid conflicts of interest, and by his overt willingness to make money off his presidency by having foreign diplomats stay at his Washington hotel, and promoting his various golf clubs.

These were not just ethical lapses. They directly undermined the common good by reducing the public’s trust in the office of the president.

When, as a presidential nominee in 2016, Trump said that a particular federal judge shouldn’t be hearing a case against him because the judge’s parents were Mexican, Trump did more than insult a member of the judiciary; he attacked the impartiality of America’s legal system.

When Trump threatened to “loosen” federal libel laws so he could sue news organizations that were critical of him, and, later, to revoke the licenses of networks critical of him, he wasn’t just bullying the media; he was threatening the freedom and integrity of the press.

When, as president, he equated neo-Nazis and Ku Klux Klan members with counter-demonstrators in Charlottesville, Virginia, by blaming “both sides” for the violence, he wasn’t being neutral. He was condoning white supremacists, thereby undermining equal rights.

When he pardoned Joe Arpaio, the former sheriff of Maricopa County, Arizona, for a criminal contempt conviction, he wasn’t just signaling it’s okay for the police to engage in brutal violations of civil rights. He was also subverting the rule of law by impairing the judiciary’s power to force public officials to abide by court decisions.

When he criticized NFL players for kneeling during the national anthem, he wasn’t really asking that they demonstrate their patriotism; he was disrespecting their — and, indirectly, everyone’s — freedom of speech. In all these ways, Trump undermined core values of our democracy.

When he accused undocumented immigrants from Mexico of murdering and raping Americans, Trump didn’t just lie. He also legitimized bigotry.

While many Americans harbored anti-immigrant feelings before Trump, they kept those feelings to themselves. Perhaps they didn’t even allow them to rise to full consciousness. That’s because such sentiments were assumed to be wrong — to violate the common good. But after Trump, such bigotry became more acceptable.

BEFORE TRUMP, the peaceful transfer of power was assumed to be a central feature of our democracy. When losing candidates congratulate winners and deliver gracious concession speeches, they demonstrate their commitment to the democratic system over any specific outcome they fought to achieve.

That demonstration is an important means of reestablishing civility. Think of Al Gore’s gracious concession speech to George W. Bush in 2000, following five weeks of a bitterly contested election and just one day after the Supreme Court ruled 5–4 in favor of Bush:

“I say to President-elect Bush that what remains of partisan rancor must now be put aside, and may God bless his stewardship of this country. . . . Neither he nor I anticipated this long and difficult road. Certainly neither of us wanted it to happen. Yet it came, and now it has ended resolved, as it must be resolved, through the honored institutions of our democracy.

Bush’s response was no less gracious:

“Vice President Gore and I put our hearts and hopes into our campaigns; we both gave it our all. We shared similar emotions. I understand how difficult this moment must be for Vice President Gore and his family. . . Americans share hopes and goals and values far more important than any political disagreements. Republicans want the best for our nation. And so do Democrats. Our votes may differ, but not our hopes.”

Many voters continued to doubt the legitimacy of Bush’s victory, but there was no civil war. Think of what might have occurred if Gore had bitterly accused Bush of winning fraudulently and blamed the five Republican appointees on the Supreme Court for siding with Bush for partisan reasons.

Think what might have happened if, during his campaign, Bush had promised to put Gore in jail for various improprieties, and then, after he won, accused Gore (or Bill Clinton) of spying on him during the campaign and trying to use the FBI and CIA to bring his downfall.

These statements — close to ones that Donald Trump actually made — might have imperiled the political stability of the nation. They would have sacrificed the common good to an extreme form of whatever-it-takes politics.

Instead, Gore and Bush made the same moral choice their predecessors had made at the end of every previous American presidential election, and for the same reason: They understood that the peaceful transition of power confirmed the nation’s commitment to the Constitution, which was far more important than their own losses or wins. It was a matter of public morality. Trump had no such concern.

When Trump sought to overturn the results of the 2020 election — by bullying state election officials to change their tallies, pushing Vice President Mike Pence to refuse to certify electors, trying to persuade Republican members of Congress to vote against certification, organizing slates of “fake” electors pledged to him, and summoning his followers to Washington to wreak havoc at the Capitol — he did not simply attack American democracy.

He undermined the norms on which American democracy is based. He in effect told Americans they should not trust our system of elections.

And now he is attacking federal prosecutors and judges, accusing them of acting out of political animus — thereby undermining public trust in our system of justice.

In all these ways, Trump sacrificed the processes and institutions of American democracy to his own selfish goals. He abused the nation’s capacity for self-government. He destroyed some of our common good.

Trump’s approach to leadership has been the opposite of John McCain’s. McCain elevated the common good. Trump has exploited and degraded it at every turn.

CEOs and directors of major corporations are also entrusted with the common good. It is no excuse for them to argue they have no choice but to do whatever it takes to maximize share prices. No law requires them to do this.

As I’ve shown, the idea that the sole purpose of a corporation is to maximize share prices is relatively new, dating back to the 1980s. The dominant view for decades before had been that corporations are responsible to all their stakeholders — to the common good.

When CEOs do whatever it takes to maximize share prices — including flooding politics with money to get changes in the law that help them make even more money — they are not acting as leaders of major institutions in American society. They are indulging in personal greed.

We can help resurrect the common good by demanding that our leaders — both in government and in business — dedicate themselves to rebuilding public trust in the institutions they have responsibility for. Their goal must be the common good rather than their own selfish, parched ambitions.

They will not do this on their own. The rest of us must make them. We must support candidates who embody this conception of leadership and eschew those who do not. We must support corporations whose leaders embody it and avoid corporations whose leaders do not.

***

Next week, I want to talk about another thing we can do to help resurrect the common good — revive public honor and shame.

Thank you once again for joining me on this journey.

These weekly essays are based on chapters from my book THE COMMON GOOD, in which I apply the framework of the book to recent events and to the upcoming election. (Should you wish to read the book, here’s a link.)

Subscribers to this newsletter are keeping it going. If you are able, please consider a paid or gift subscription. And we always appreciate your sharing our content with others and leaving your thoughts in the comments.

Thank you, Robert. What a rich and compelling argument. I think the damage Trump and the authoritarian Republicans have caused is acute and becoming clearer every day, but it has been growing over decades as a culture of greed. You describe a good test for evaluating leaders and positions and even our own actions - always trying to consider the common good. I know there are many good people who must work together now to defend our country.

Thank you kindly Dr. Reich. I needed this tonight, as I grieve my best friend's dog, a regal English Springer Spaniel who passed last evening. I never had any children, but Sir Fleetwood Charlee shall remain forever in my heart. I know this probably seems like a weird response to your essay, but somehow your words always give me hope and reassurance in many ways. As a life long Democrat, I truly admired John McCain and the torture he suffered. I wish we could realize once again how much we miss what holds us together, not that tears us apart. Thank you again for your wisdom. It would have been an honor to take one of your courses. Thanks as well for allowing my somewhat digression in lamenting the passing of a dog responding to your wonderful love of this country. Blessings to you Dr. Reich.