To be "Borked": My odd friendship with Robert Bork

And how his nomination fight was the beginning of the end of civil discourse in Washington

Did you ever admire someone whose views and opinions you disliked?

Last week’s news that the Justice Department is filing an antitrust lawsuit to break up Google’s advertising business led me to remember one such person. His name was Robert Bork. More than any single person, Bork almost killed antitrust in America.

I met Bork in 1971 when I took his class on antitrust at Yale Law School.

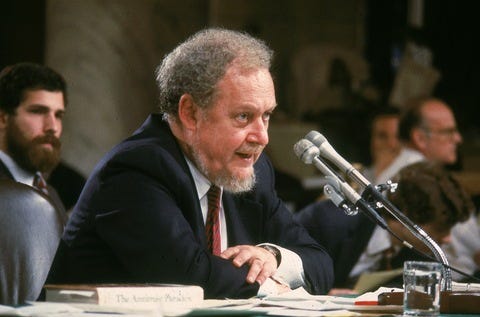

I recall him as a large, imposing man, with a red beard and a perpetual scowl. He was only in his mid-40s then, but he seemed impatient and bored with us (also in that class were Hillary Rodham and Bill Clinton).

We kept challenging his view that the only legitimate purpose of antitrust law was to lower consumer prices.

“What about the political power of giant corporations?” we asked.

His retort: “How do you expect courts to measure political power?”

“But what about the power of big corporations to suppress wages?”

“Employees are always free to find better jobs.”

“What about their power to undercut potential rivals with lower prices?”

“Lower prices are good for consumers.”

“What about the sheer power that comes from their gigantic size?”

“Also good for consumers. Large size means lower costs through efficiencies of scale.”

Bork had an answer to all of our objections, but we were never satisfied. He spouted economic theory based on dubious “Chicago School” assumptions that all economic players have perfect information and face no cost of entering or leaving markets (Bork had attended the University of Chicago and its law school).

Even in our early and mid-20s, we knew this was bullshit. Bork refused to recognize power, although antitrust laws emerged from the Gilded Age of the late 19th century when a central concern was the untrammeled power of giant corporations.

A few years after that, Bork wrote a book called The Antitrust Paradox that summarized his ideas. The staff of a conservative California governor bound for the White House read it and passed it along to their boss, and Bork’s book formed a basic tenet of Reaganomics.

Federal judges read it, too. Most judges didn’t (and still don’t) know much economics and hated getting bogged down in interminable and almost incomprehensible antitrust trials that could last for years. They found Bork’s simplicity and cogency helpful in limiting such lawsuits.

As a result, antitrust nearly became a dead letter. (Joe Biden is now busily reviving it.)

I forgave Bork’s narrow approach to antitrust. I enjoyed his wry sense of humor. I respected his intellect. Hell, I even came to like him.

Richard Nixon appointed Bork solicitor general — the third-ranking official in the Justice Department, representing the United States before the Supreme Court. Bork was known as a conservative, but as solicitor general he filed liberal friend-of-the-court briefs on the side of litigants seeking expansive rights — as often as did Thurgood Marshall when Marshall served as solicitor general in the Johnson administration and even more often than Wade McCree did during the Carter administration. In civil rights cases, Bork filed briefs in favor of those seeking broader readings of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts some 75 percent of the time.

In what came to be known as the “Saturday Night Massacre,” in October of 1973, Bork briefly became acting attorney general after his superiors in the Justice Department chose to resign rather than fire Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, who was investigating the Watergate scandal. Following an order from Nixon, Bork fired Cox. It was Bork’s first official assignment as acting attorney general.

He served as acting attorney general until January 4, 1974, and then resumed his duties as solicitor general. Nixon resigned, and Gerald Ford kept him on.

A few months later, Bork offered me a job as assistant to the solicitor general.

Why me? Maybe he remembered me from his Yale Law classes and my pugilistic responses to his arguments. More likely, after firing Archibald Cox, he couldn’t find anyone else.

Why did I take the job? I was still in my 20s, thrilled at the prospect of briefing and arguing cases before the Supreme Court. Nixon was no longer president. It never occurred to me that I might have to compromise my beliefs — and I didn’t, because I was never assigned an important case that countered them.

I did not distinguish myself on the job, however. In one of my arguments before the court, I mistakenly referred to Justice Potter Stewart as Justice William Brennan — an error that the two justices found hilariously funny but made me want to disappear under the podium where I was standing. Bork was forgiving.

I saw Bork just once after he left the Justice Department. It was at the start of the 1980s, at a dinner party at his house in Washington. He was in a festive mood. He had remarried (his first wife had died of cancer a few years before), and seemed happy. His sharp wit was much on display.

In 1982, Reagan appointed him to the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, and in 1987, after Justice Lewis Powell announced his retirement, Reagan nominated him to the Supreme Court.

You probably remember what happened next. All hell broke loose. Bork’s Supreme Court nomination precipitated the first scorched-earth, no-holds-barred combat I had witnessed in Washington.

Democrats were determined to prevent Bork from getting on the court, in large part, I think, because of his role in the Saturday Night Massacre. They put out unfounded rumors that made him seem way out of the conservative mainstream. Someone went through Bork’s trash cans looking for anything that might incriminate him (and found nothing). Another went to his local video rental store, seeking records of what films he’d checked out (again, nothing). TV ads produced by People For the American Way, and narrated by Gregory Peck, attacked him as an extremist.

Senator Ted Kennedy (who later became one of my dearest friends) said on the Senate floor in opposition to Bork’s nomination:

“Robert Bork’s America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of the government, and the doors of the federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens for whom the judiciary is, and is often the only, protector of the individual rights that are the heart of our democracy.”

This was unfair. I had worked closely with Bork. His views had become more conservative over time, but he was not the extremist Kennedy described.

Bork didn’t help himself. During his confirmation hearing, when asked why he wanted to be a Supreme Court justice, he said it would be intellectually stimulating. And he didn’t make any attempt to hide his conservative philosophy.

His nomination was ultimately rejected by the Senate, 42–58.

The campaign against Bork added a new verb to the American lexicon: to be “Borked” — defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “to defame or vilify someone systematically, especially in the mass media, usually to prevent his or her appointment to public office.”

In the years since the Bork nomination fight, many people have been Borked — notably, Bill and Hillary Clinton and John Kerry, when he ran for president. After his own Senate confirmation fight, Brett Kavanaugh claimed that his opponents had engaged in “a good old-fashioned attempt at borking," but the analogy didn’t hold. Serious accusations were leveled at Kavanaugh, touching directly on his moral character and capacity to be a Supreme Court justice — charges that continue to cloud the public’s view of him. Bork’s moral character was never questioned.

To me, the fight over Bork’s nomination was the beginning of the end of civil discourse in American politics. I was shocked by it. Although I was frankly relieved that Bork would not be on the Supreme Court (his views had become far too conservative for my taste), I thought he was treated horribly.

Angry and bitter, Bork resigned his appellate court judgeship the following year. He subsequently became one of the nation’s first right-wing cultural warriors.

I found this excerpt from his 1996 book, Slouching Towards Gomorrah: Modern Liberalism and America’s Decline, especially poignant because Bork could well have been writing about my classmates and me.

One morning on my way to teach a class at the Yale law school, I found on the sidewalk outside the building heaps of smoldering books that had been burned in the law library. They were a small symbol of what was happening on campuses across the nation: violence, destruction of property, mindless hatred of law, authority, and tradition. I stood there, uncomprehending, as a photograph in the next day’s New York Times clearly showed. What did they want, these students? What conceivable goals led them to this and to the general havoc they were wreaking on the university? Living in the Sixties, my faculty colleague and I had no understanding of what it was all about, where it came from, or how long the misery would last. It was only much later that a degree of understanding came.

Bork saw the Fifties and Sixties as sources of everything that he viewed as destructive to America — including Bill and Hillary.

We noticed (who could help but notice?) Elvis Presley, rock music, James Dean, the radical sociologist C. Wright Mills, Jack Kerouac and the Beats. We did not understand, however, that far from being isolated curiosities, these were harbingers of a new culture that would shortly burst upon us and sweep us into a different country.

The Fifties were the years of Eisenhower’s presidency. Our domestic world seemed normal and, for the most part, almost placid. The signs were misleading. Politics is a lagging indicator. Culture eventually makes politics. The cultural seepages of the Fifties strengthened and became a torrent that swept through the nation in the Sixties …. The spirit of the Sixties revived in the Eighties and brought us at last to Bill and Hillary Clinton, the very personifications of the Sixties generation arrived at early middle age with its ideological baggage intact.

Bork still didn’t understand power. What he described as “ideological baggage” emerged from our generation’s experience with the civil rights movement, Vietnam, and Richard Nixon. We were weaned on the moral necessity of remedying abuses of power. The antitrust movement that began more than a century ago and is being revived today has a similar root. Bork was unable to understand it, either.

Robert Bork died in December 2012.

Open letter to the media,

Please stop broadcasting Trumps comments and speeches.

Trump manipulated people into participating in a violent insurrection to overthrow the government of the United States.

Doesn't that concern you????

Anytime Trump speaks publicly, it is for his own benefit.

He is trying to gain approval with the public in hopes that his next insurrection will succeed.

When his followers hear or see him in the media it boosts their confidence in him and makes them more apt to do what he wants them to do.

Every time you put one of Donald Trumps speeches or comments out to the public, you are participating in Trumps next insurrection attempt.

Please, With all due respect:

Stop giving Trump a megaphone.

A few replies to Prof. Bork:

“How do you expect courts to measure political power?”

In an era decades before SCOTUS’s Citizens United decision, political power could be calculated by the dollar, and the government had the right to regulate corporations’ donations to insure that government did not become a wholly-owned subsidiary of those corporations.

“Employees are always free to find better jobs.”

So spoke a tenured-for-life professor who could be fired only for cause.

“Lower prices are good for consumers.”

Companies lower prices for one reason only: to build market share, ideally to the point that they acquire their competitors or force them to go out of business. At the point that they achieve overwhelming control of the market with no serious competitors, they then raise their prices. And raise their prices. And raise their prices.

“Also good for consumers. Large size means lower costs through efficiencies of scale.”

Efficiencies that are then passed on to shareholders in the form of dividends and stock buy-backs, and to top executives in the form of raises, bonuses and stock options. Lower prices do not follow lower costs as darkness follows day.