The awful, horrible, detestable year of 1968

Idealism and failure

Friends,

The uncertainty about what younger voters are likely to do next fall brings me back to 1968 — the first modern presidential election in which young activists played a prominent role.

I was one of them.

It was an awful year. Those of you who were alive then surely remember.

Lyndon Johnson was escalating the Vietnam War. Nearly half a million American combat troops were already there. All told, more than 58,000 Americans and 2 million Vietnamese would die in that nightmare.

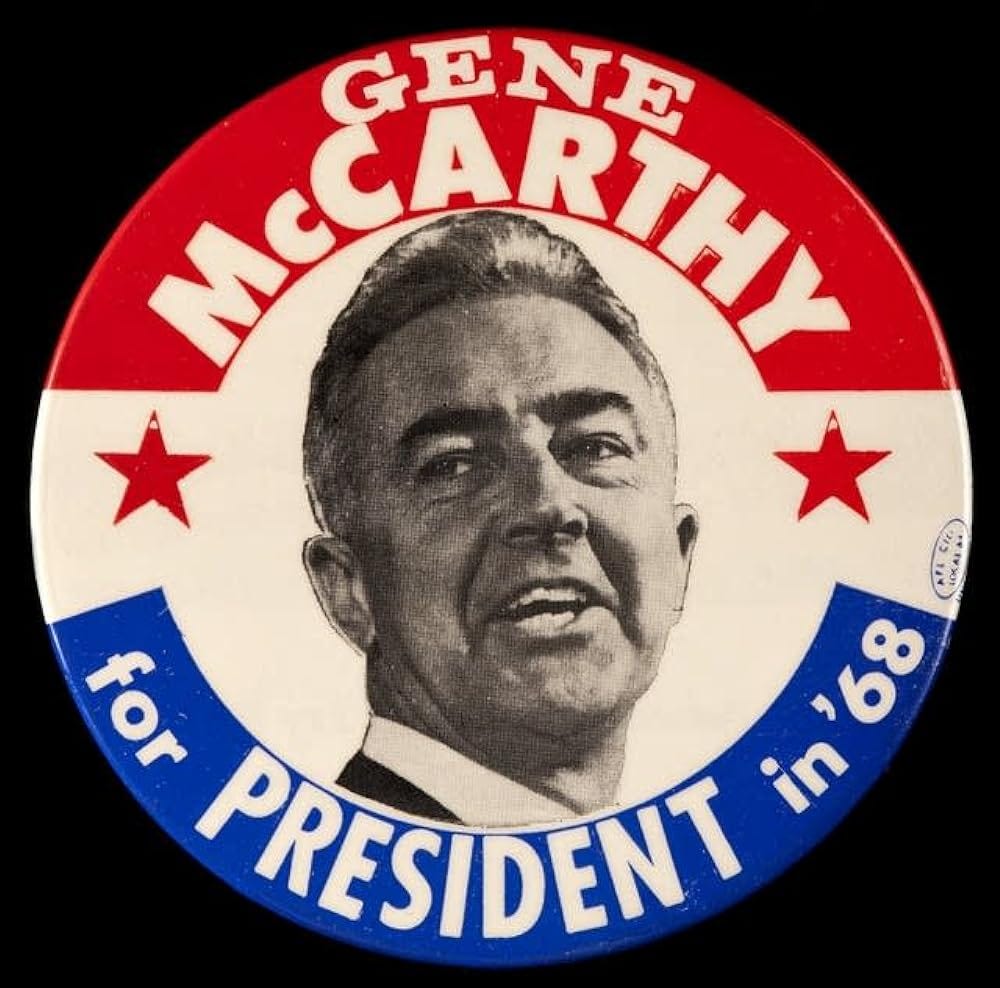

CITING THE IMPORTANCE OF ENDING the war, Senator Eugene McCarthy entered the Democratic presidential primary race against Johnson in November 1967.

McCarthy was a tall, thin, mild-mannered politician from Minnesota. Some found him rather remote and professorial. He wrote poetry and spoke eloquently about the ideals of America.

He claimed that America was suffering from a “deepening moral crisis” and helplessness that he hoped to alleviate.

He rejected the long-accepted wisdom that stopping communism required resisting it actively everywhere, including Vietnam. He especially rejected the practice of propping up unpopular dictators and the supposed necessity of sending half a million troops to fight in jungles half a world away.

McCarthy had encouraged Robert F. Kennedy to enter the race, but Kennedy didn’t want to challenge Johnson and publicly announced he’d support Johnson as the nominee. Kennedy predicted that McCarthy’s campaign would have a “healthy influence” on Johnson, who he predicted would ultimately win the nomination.

ON JANUARY 30, 1968, North Vietnam launched the Tet Offensive — a ferocious attack on the cities of South Vietnam, including the U.S. embassy in Saigon. The attack’s success belied Johnson’s claim that the Americans and the South Vietnamese were winning the war.

After three years of bombing and mounting casualties, America seemed farther from victory than ever.

I was in the middle of my senior year at Dartmouth. I had been protesting the war by standing on the campus with an antiwar sign, along with hundreds of other students. I remember asking myself whether our pathetic little protest would have any impact. We were in Hanover, New Hampshire, after all.

I felt I had to do something more.

Soon after the Tet Offensive, I got a call from a friend who had left college to work on the McCarthy campaign. He said the campaign needed students to go door-to-door for McCarthy in every state with Democratic primaries and caucuses. My friend suggested I help recruit them.

Within hours, I was in my green VW Beetle, heading west.

My first stop was Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where Sarah was a senior. (To protect her privacy, I won’t use her real name.) I had met Sarah at an educational reform workshop at Dartmouth. I thought she might lend a hand to the McCarthy campaign. I was right. She packed her bag and joined me, heading toward other college campuses.

Sarah wasn’t much taller than I was. She had bright blue eyes and an impish grin. Her voice was low and melodic, her laugh infectious. She also had a dark side. She could be deadly serious when talking politics or about the future of the world.

Over the next few months, Sarah and I visited more than 40 universities across Indiana, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Wisconsin, New Hampshire, and California.

Wherever we stopped, we hauled out a 35-millimeter projector, set it on a table in whatever room we could find, and looped through its sprockets a 10-minute film of Eugene McCarthy talking directly to the camera about the importance of his campaign and why he needed students to join him.

Sarah and I then gave short lectures on how to go door-to-door, what to ask for, how to ask, what to wear, and the importance of looking respectable — keeping “clean for Gene.”

After every session, hundreds of students signed up. We collected their names and passed them on to organizers in states holding primaries and caucuses. Like Sarah and me, most of these students left behind their campuses and courses to join the McCarthy campaign.

We were part of what the press dubbed “McCarthy’s children’s crusade.”

And we were on a roll. McCarthy seemed to be gaining ground. Three precincts in Minnesota supported McCarthy delegates — a blow to Johnson, whose vice president, Hubert Humphrey, was a Minnesotan. Then Johnson abandoned Massachusetts, which gave its 72 delegates to McCarthy.

We felt like revolutionaries in a peaceful revolution that was succeeding beyond anyone’s expectations. The number of students showing up at our recruitment sessions grew larger at every stop.

We didn’t think much about the thousands of young men not attending college who were being drafted or enlisting. Nor about families and communities for whom patriotism took precedence over qualms about Vietnam. Nor did we focus our efforts on members of labor unions or on Black Americans or Latinos. Our world was the growing antiwar movement on mostly white college campuses.

It would prove a profound error. The coalition that had propelled the New Deal and been temporarily revived by John F. Kennedy connected unionized workers, the poor, Catholics, Black and Latino Americans, students, and intellectuals. But the antiwar movement we participated in was mostly students and intellectuals.

[Lyndon Johnson]

SARAH AND I HIT NEW HAMPSHIRE at the beginning of March.

Opinion polls prior to that first-in-the-nation primary showed McCarthy’s support at only 10 to 20 percent. Johnson’s campaign circulated pamphlets saying that “the communists in Vietnam are watching the New Hampshire primary ... don’t vote for fuzzy thinking and surrender.”

But the polls didn’t show the depth of disaffection among independents and others who could vote in the Democratic primary. And the polls missed a late surge in voter interest spurred in part by hundreds of young college volunteers who streamed into the state to campaign for McCarthy — some of them, courtesy of Sarah and me.

On March 12, McCarthy stunned the political establishment by winning 42.2 percent of the vote in the New Hampshire primary. Johnson got 49.4 percent. It was seen as an upset and a huge blow to the incumbent president.

On primary night, McCarthy was jubilant:

“People have remarked that this campaign has brought young people back into the system, but it’s the other way around. The young people have brought the country back into the system.”

Sarah and I thought he was speaking about us.

McCarthy’s surprise showing in New Hampshire had a larger consequence: On March 31, Johnson announced he was dropping out of the race and would not run for reelection.

The New York Times ran a three-tiered headline:

JOHNSON SAYS HE WON’T RUN;

HALTS NORTH VIETNAM RAIDS;

BIDS HANOI JOIN PEACE MOVES.

It is hard to convey to you now, almost 56 years later, the sense of triumph we experienced. Johnson would be gone! The dreaded Vietnam War would end! The “children’s crusade” had slayed the dragon!

(Meanwhile, I had fallen for Sarah. She was my first real romance. Like Philip Larkin, it was rather late for me, but my infatuation made up for my tardiness.)

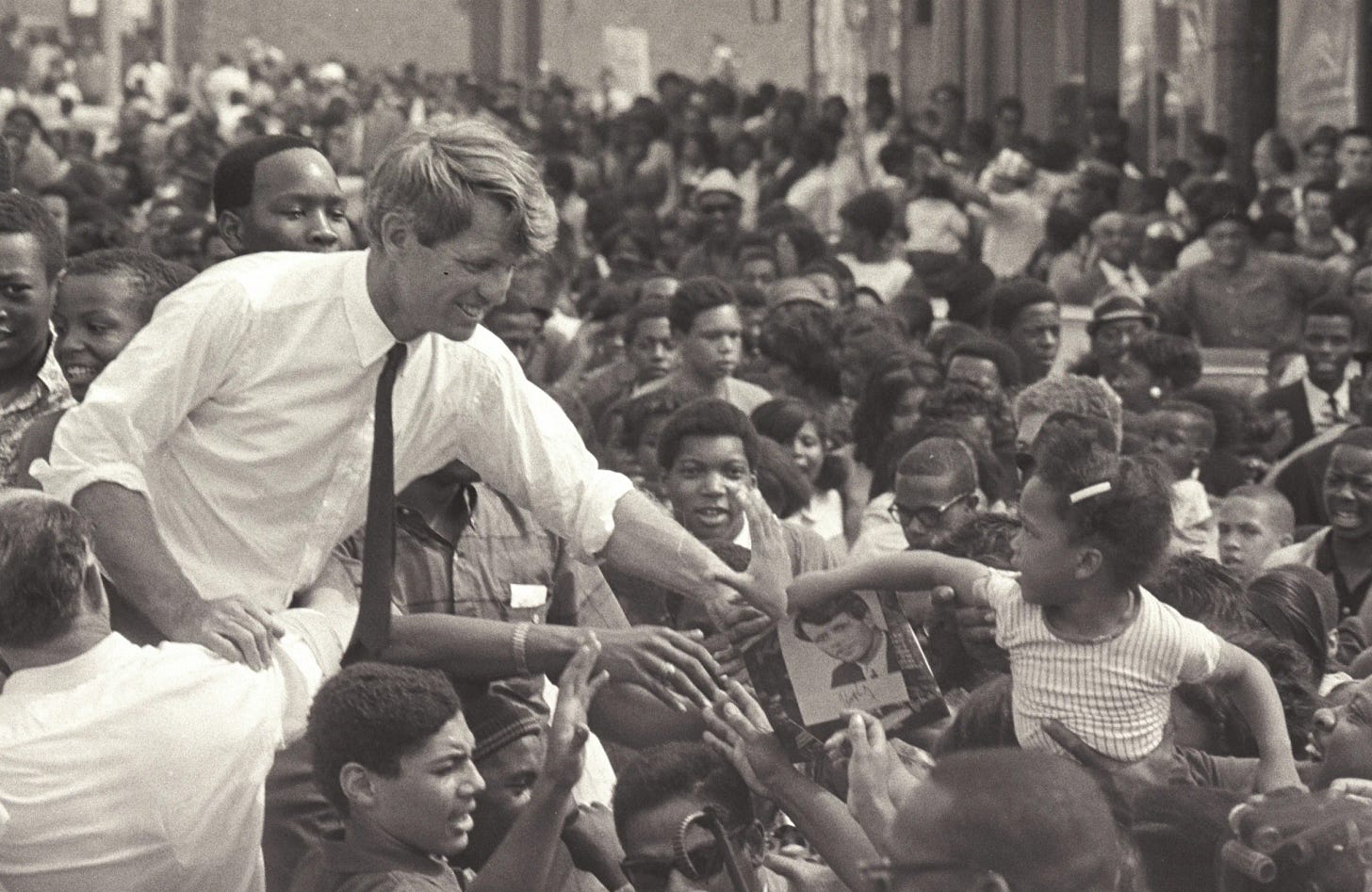

McCARTHY’S VICTORY OVER JOHNSON would have felt clearer to me had Robert F. Kennedy not entered the race. In announcing his candidacy, Kennedy said:

“I do not run for the presidency merely to oppose any man, but to propose new policies. I run because I am convinced that this country is on a perilous course and because I have such strong feelings about what must be done, and I feel that I’m obliged to do all I can.”

Almost immediately, Kennedy soared to first place in polls of Democratic voters.

WHAT WAS I TO DO? I’d worked for Kennedy the preceding summer. I knew many of his key staffers and political advisers.

Yet I had been pouring my heart into McCarthy’s campaign. I believed in McCarthy. I admired his courage and his integrity. I had convinced thousands of students to join his children’s crusade. How could I possibly switch to Kennedy’s campaign?

And, of course, there was Sarah. What would she think of me if I abandoned McCarthy?

Kennedy’s decision to run struck me as patently opportunistic. Only months before, he had said he wasn’t going to. Only after McCarthy demonstrated the public’s antipathy to the war and the popularity of an antiwar candidate did Kennedy jump in.

I recalled how angry Kennedy had been with me the summer before, for getting interns on Capitol Hill to sign my antiwar petition — worried about his relationship with Johnson.

I would stay with McCarthy.

On March 27, Kennedy announced his intention to run against McCarthy in the Indiana primary. It would be the first head-to-head race between them.

Sarah and I headed to Indiana. At Indiana University, we collected names of hundreds of student volunteers.

That same afternoon, I ran into Kennedy’s chief of staff, Joe Dolan, on Washington Street in Indianapolis.

“Well, look who’s here!” Joe said with a slight grin. “Didn’t know you were on the campaign.”

“Joe,” I said haltingly, “I’m here for McCarthy.”

Without a word, Dolan spun around and walked in the opposite direction.

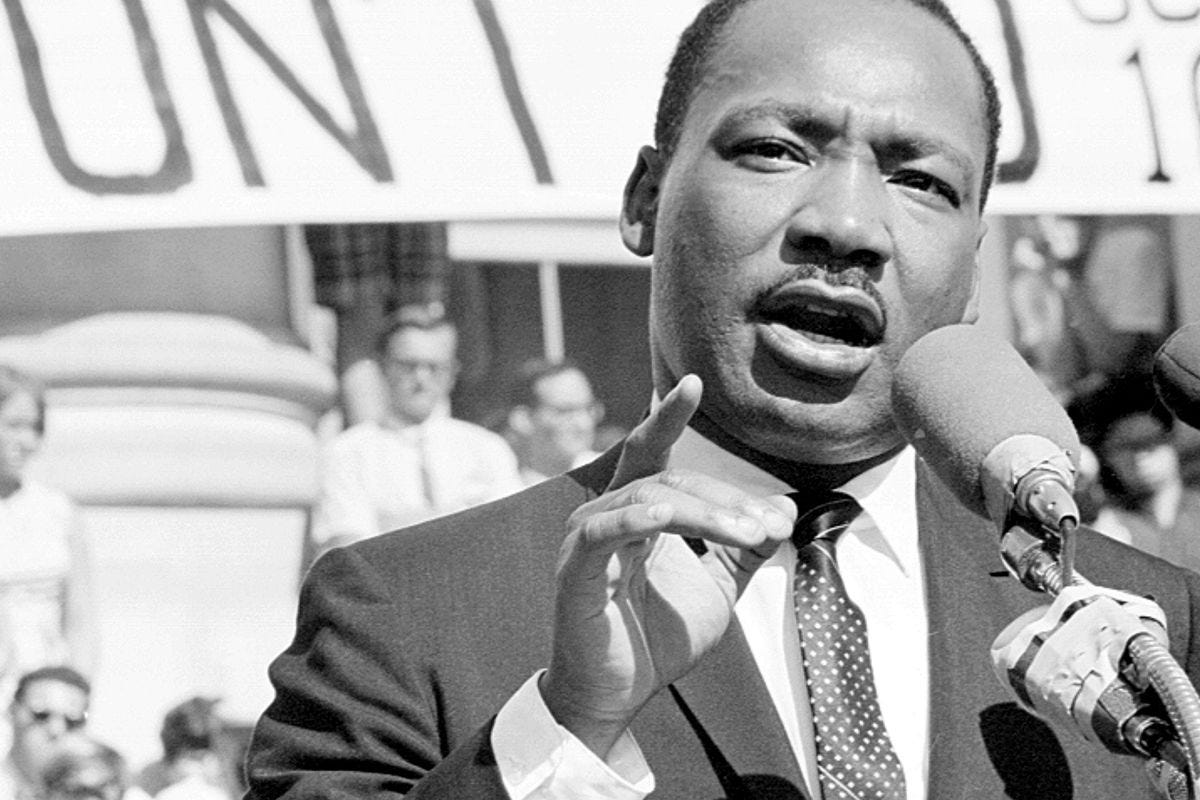

ON THURSDAY, APRIL 4, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated by a white ex-convict while standing on a balcony outside his second-floor room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

King had come to Memphis to lead a march by striking sanitation workers, and to criticize the Vietnam War.

King’s condemnation of racial inequalities had grown to embrace economic inequalities such as those faced by the sanitation workers. King’s views about the Vietnam War had likewise grown to include a more radical critique of what he saw as U.S. militarism and imperialism.

As news of King’s murder spread, riots broke out in 130 cities, resulting in more than 40 deaths nationwide.

It felt to me as if America was coming apart.

Without skipping a beat, California’s then governor, Ronald Reagan, called King’s assassination part of the “great tragedy that began when we began compromising with law and order, and people started choosing which laws they’d break.”

Stokely Carmichael, who had headed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, told a crowd in Washington, D.C., that “white America killed Dr. King” and had “declared war on black America,” and that they should “go home and get your guns.”

McCarthy tried to calm the crowds, but he had a hard time connecting with Black Americans.

Meanwhile, Kennedy — speaking from the back of a flatbed truck in Indianapolis — told a large group of angry Black people that “what we need in the United States is not division, not hatred, not violence and lawlessness, but love and wisdom and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black.”

I was moved by Kennedy’s eloquence.

Kennedy won the Indiana primary with 42 percent of the vote. A native son came in second. McCarthy was third, with only 27 percent.

Our attention shifted to the upcoming primary in California. We assumed it would be determinative. Kennedy said he’d exit the race if he lost.

Sarah and I drove up and down the huge state, recruiting hundreds of students for McCarthy at California’s many colleges and universities.

As McCarthy stumped those same campuses, he was treated as a hero for being the first presidential candidate to oppose the war. Kennedy campaigned in the ghettos and barrios of the state’s larger cities, where he was mobbed by enthusiastic supporters.

On June 5, just after winning the California primary, Kennedy was shot while leaving the ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, where his supporters had gathered to celebrate his victory.

McCarthy immediately canceled his campaign plans and was placed under heavy guard in his hotel.

Kennedy died the next day.

McCarthy was grief-stricken and considered dropping out of the race.

I was devastated. All my ambivalence about Kennedy disappeared. I thought about his powerful words, his commitment to social justice. I questioned why I had even campaigned for McCarthy.

Mostly, though, I wanted nothing more to do with American politics.

Sarah couldn’t stop crying. She was overcome by darkness. She wanted to go back to Ohio.

We packed up my green VW Beetle. I dropped her off in Antioch and made it back to Dartmouth barely in time to graduate.

WHEN THE DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL CONVENTION opened in Chicago, delegates were greeted with violent demonstrations against the war. During the following days, young people who had been lured into politics by McCarthy’s antiwar campaign and by Robert Kennedy’s call for social justice were beaten by the Chicago police.

The delegates chose Hubert Humphrey as their presidential nominee. Humphrey hadn’t even appeared on any primary ballot. His campaign had concentrated on winning delegates from non-primary states where party leaders controlled the votes.

Even then, Humphrey was reluctant to come out against the war. He waited until the final weeks of the presidential campaign to break with Johnson over Vietnam.

After ending his campaign, McCarthy said he had “set out to prove ... that the people of this country could be educated and make a decent judgment ... but evidently this is something the politicians were afraid to face up to.”

Humphrey lost the presidency to Richard Nixon.

Humphrey’s nomination marked the end of the Democrats’ New Deal coalition.

It was also the end of my romance with Sarah. That broke my young heart.

I turned 18 in March of 1968 and didn't have the right to vote although 18 year old young men were being drafted to fight in Vietnam. My high school boyfriend joined the Marines because he had a low draft number. I was focused on earning enough money as a waitress after graduation to buy a car, support myself, and afford classes at the new Junior College, Rock Valley. Many young working people today are focused on surviving and not on politics. We need to educated them about how the world works and get them registered to vote.

Gee, Professor, you might want to write (yet) another book! What a story! What a life you have led…

Let us only hope some of today’s youth with have the spunk and the drive to better this country now, as you and Sarah did back in the ‘60’s.

Your friend in MD,

Anne 🌻💙🙏